Abandoned in Assam: India creates its own Rohingya, and calls them ‘Bangladeshi’

- Mass statelessness looms for millions after harrowing, often fatal, citizenship test to find illegal immigrants

- Project to showcase Hindu primacy threatens to disenfranchise both Hindu and Muslim Bengali speakers

Feeding the panic, a state-owned bank was found burning its stock of cash to prevent it from falling into Chinese hands, and a district administrator reportedly freed the inmates of a mental asylum before fleeing the town himself. Locals recount the inmates raising pro-China slogans, thinking the Chinese army had freed them.

It did not help that then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, in a November 20 radio address to inform the nation of Indian losses, said his “heart goes out to the people of Assam”. There couldn’t have been a surer sign of New Delhi preparing to concede Assam. But as Assam counted down the hours to certain doom, Beijing suddenly announced a unilateral ceasefire and began to pull back. The war ended just as unexpectedly as it started a month before, and Assam’s place in India was secure again.

But Suro Debi’s struggle to ensure hers was only beginning.

One morning, in the closing days of the war, Mukti Debi, a slum dweller in the Assamese capital Guwahati (then called Gauhati), found a newborn girl lying abandoned by the road. Mukti took her home, named her Suro, and raised her as her own. When Suro entered her teens, she fell in love with Kamini Singha, a local carpenter. They married, set up house, and had a daughter. Kamini, however, died young, leaving an unlettered Suro to fend for herself and her five-year-old.

She began to work as a domestic helper and came to know the Guhas. Amalendu Guha, a famous historian, and his wife Amiya, also a noted academic, had just returned to Assam after teaching stints in different parts of India. Suro started working for them, and, over the years, began to live with the Guhas as a carer. When Amalendu passed away, she became Amiya’s full-time attendant, and the daughter Amiya never had. With her own daughter having married and settled down, life had smiled on Suro again. She had again managed to find a home – but a homeland was a different matter.

Suro, who has never stepped outside her central Guwahati neighbourhood in all her 59 years, is now at the risk of being branded an illegal migrant. As Assam prepares its list of legal Indian citizens, Suro is among the 4.1 million people who have so far failed to make the cut. When the final list is declared on August 31, she will know if she has been abandoned all over again, this time by the state.

Bengali Muslim: what next for Assam’s forever foreigners in Modi’s India?

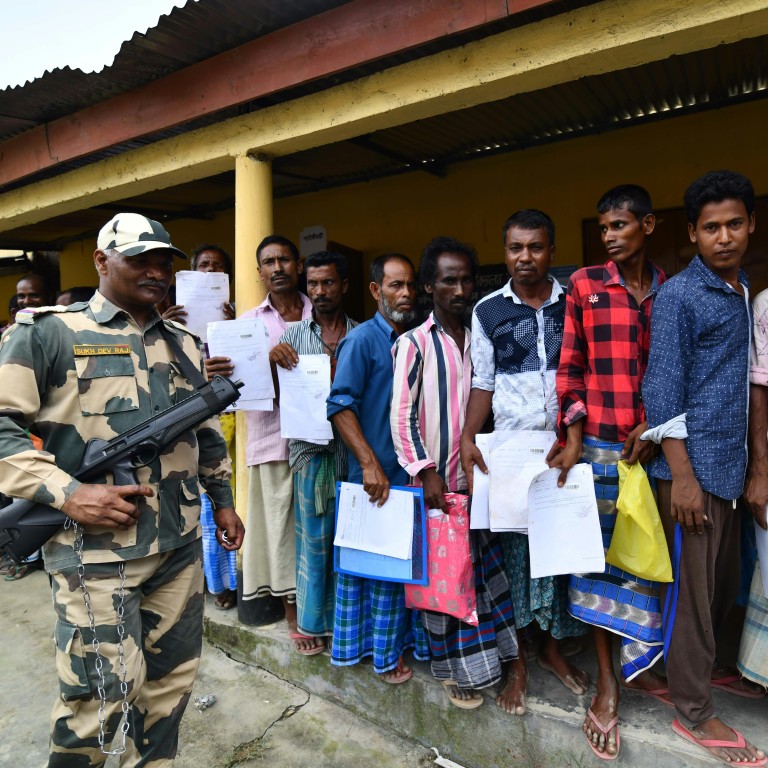

A GIANT EXERCISE

Assam is updating the 1951 National Register of Citizens (NRC) – the only province in India to do so – to separate Indian citizens from undocumented immigrants, mostly from what is now Bangladesh and was once part of Pakistan, and, before that, undivided British India. The first complete NRC draft, published on July 30 last year, left out over 4 million people. Another 100,000 people were removed in June. The biggest province in India’s mountainous northeast, Assam’s population is estimated at 35 million.

The final NRC list is being compiled after cross-examinations of the 3.1 million who appealed against their exclusion. How many names will finally be left out is anybody’s guess, but if the two earlier lists are any indication, there are at least hundreds of thousands of people who stand to be declared stateless in a country they know to be their own. The closest regional parallel to such large-scale statelessness in recent times was the 1982 mass disenfranchisement of the Rohingya people in Myanmar, before their massacre years later that started the exodus exactly two years ago.

Some fear widespread violence and protests when the list comes out next week. Zamsher Ali, a team leader at non-profit Citizens of Justice and Peace, says activists like him are working on the ground to convince potential victims to take the legal route in challenging the decision rather than give in to desperation. His organisation – and many others – is preparing volunteers with legal and paralegal training.

The people who will be excluded are the poorest and the weakest, with little means to either sustain a legal challenge or mount political protests

“More than violence, I fear a spike in the number of suicides. The people who will be excluded are the poorest and the weakest, with little means to either sustain a legal challenge or mount political protests. After being put through untold misery to prove their citizenship, many of them will see it as the end of the road,” Ali says.

According to data from Citizens of Justice and Peace, the NRC exercise has so far driven 57 people to suicide. Born in Assam, Nirode Baran Das, 70, who had taken to practising law after retiring as a teacher, hanged himself after he received an NRC notice marking him as a foreigner. He pinned the notice to his suicide note. Hitmat Ali, 50, hanged himself in June, anxious about his wife’s name being absent from the NRC draft list. In 2016, Balijan Bibi, 43, did the same after a Foreigners’ Tribunal, a quasi-judicial body that makes citizenship judgments, declared her husband a foreigner and sent him to a detention centre.

The stress and shame over losing citizenship, and the fear of being incarcerated, have also taken lives. Gauranga Roy died of a heart attack when he learned he was not on the list. So too did Mujibar Rahman, on his way back from an NRC office, where he went to find out why his wife’s name had been struck off.

Deportation and detention: 3 million face statelessness in Assam

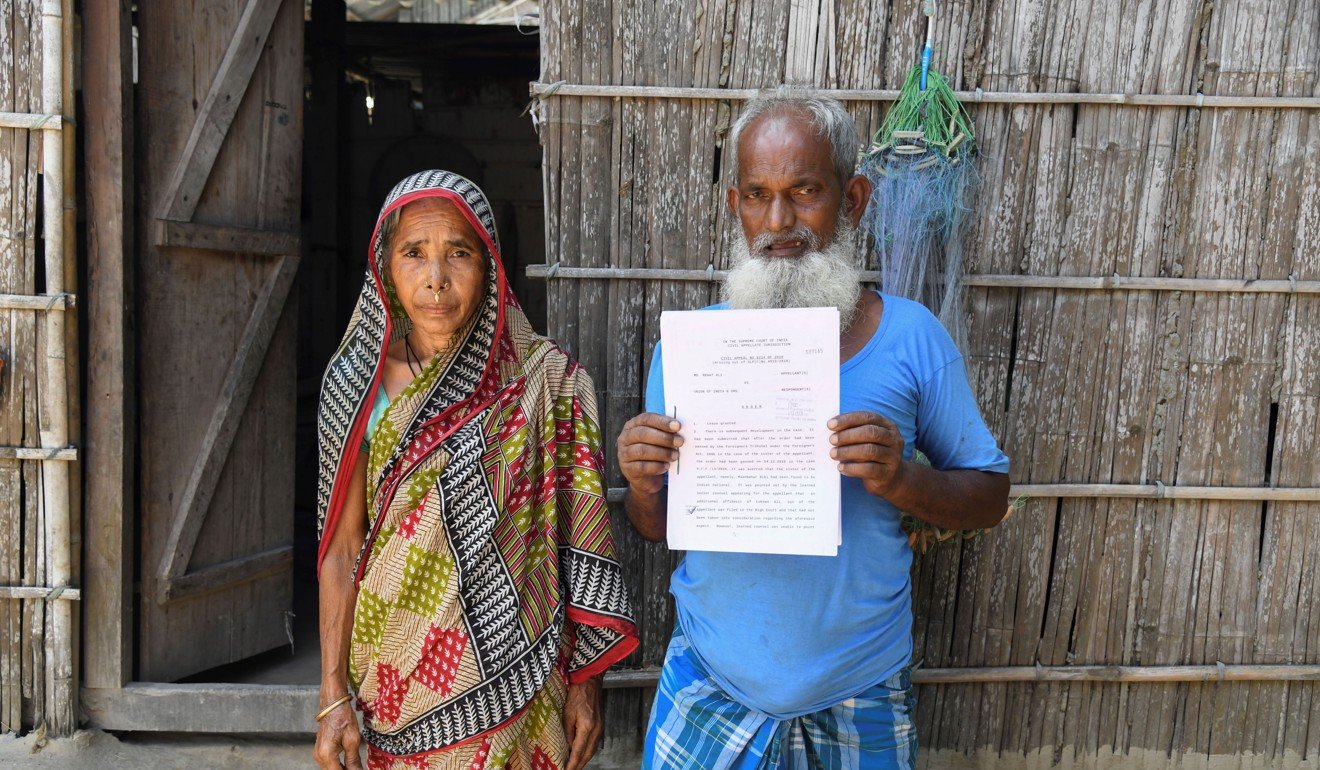

The government this week said those who found themselves excluded from the final NRC list would get four months to appeal to the tribunals and higher courts, during which time they would be able to keep their citizenship. There is no official word on what happens should their appeals be overturned.

“This is what will happen if you don’t have an NRC certificate: every time police, or even nativist vigilante mobs, demand to see your NRC certificate and you can’t produce it, you are basically at their mercy,” says Jnanendu Bikash Roy Talukdar, a Bengali-speaking native of Assam who manufactures stonecutting machines in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan. “Anything can happen, from extortion to assaults and worse. You become vulnerable from the day you are out of the NRC.”

Those who will lose citizenship are eventually liable to be incarcerated and deported, though Bangladesh has expressed no interest in taking them. That means India has to build a lot of detention centres, and quickly, or millions of people will be forced to live as second-class Indian citizens with limited rights and unlimited vulnerability.

“Stateless persons risk being deprived of access to basic rights and services that are often linked to nationality status, including access to education, health care and legal employment, the ability to buy or sell property, open bank accounts, or even get married. Statelessness can also lead to restrictions on freedom of movement and result in prolonged and arbitrary detention, as well as deportation,” UNHCR spokeswoman Liz Throssell tells This Week in Asia.

FINDING THE OTHER

Amit Shah, the Home Minister and Modi’s closest aide, refers to illegal migrants from Bangladesh as “termites” eating the country’s resources. As the BJP does not view Hindus from Bangladesh as illegal immigrants but as refugees, “Bangladeshi” has become shorthand for Muslim migrants in India. The BJP’s consistent position has been that while non-Muslims can seek asylum in India, claiming persecution in their Muslim home countries, there are no grounds for Muslim refugees from these countries to come to India. If they do, they are merely economic migrants or, worse, “infiltrators” who the government has every right to deport.

Hong Kong is in India, Kashmir is in China. Right?

In its implicit labelling of the Muslims as the outsider and the unwanted, required to prove their Indianness, the NRC has been loaded with the kind of symbolism that animates Hindu-right politics. The project also dovetailed perfectly with the historical loathing the Assamese reserve for outsiders who are seen to be taking their land and threatening their culture.

Keen to showcase Assam as a test case of Hindu primacy by expelling Muslim migrants, the BJP made it one of its prime electoral issues earlier this year. Beginning with the state, Modi’s party aims to implement the NRC across India. The government has amended an old law, empowering district magistrates all over the country to set up Foreigners’ Tribunals, which had so far been unique to Assam. The Economic Times reported that New Delhi had asked all provinces to each set up at least one detention centre with modern amenities. To help, it has reportedly issued an 11-page “2019 Model Detention Manual”. With the NRC, Assam could be the starting point of a wider sweep against Muslims.

The term Bangladeshi conveys a sense of foreignness that justifies unequal treatment. In reality, however, many among the target group came to Assam before there was a Bangladesh, and many of them are Hindus. Much to the discomfiture of the BJP, more Hindus than Muslims may be declared stateless as the NRC process is not meant to distinguish between the two. This could boomerang on Modi’s party unless the Hindus sieved out in the NRC are restituted somehow.

To do that, the BJP had planned to pilot a law change through the Citizenship Amendment Bill, providing citizenship to non-Muslim migrants from Muslim-majority Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. But the amendment had to be shelved after opposition parties in parliament objected on the grounds that it violated the spirit of India’s secular constitution.

In the northeastern states such as Assam, there was added resistance to any change in citizenship laws because of fears it would legitimise the residency rights of non-Assamese Hindu migrants. The northeast went up in flames when New Delhi tried to amend the bill in January.

Is India’s Kashmir move an attempt to shift its Muslim demographic?

Apart from a change in law, the government could try to naturalise the excluded Hindus by an ordinance, which does not require parliamentary approval. Either way, to preserve its vote base, the BJP would have to find a way to guarantee citizenship to the Hindus left out.

With a separate set of rules for Hindus while punishing Muslims, the BJP would also send a clear signal reaffirming its commitment to the Hindu cause. Coming on the heels of the abolition of the statehood of Jammu & Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state, and the anti-Muslim rhetoric and optics around the NRC, a special citizenship law only for Hindus would cement the BJP’s status as the party that shows Muslims their place in India – its prime source of appeal to its Hindu base.

It’s clear the BJP is up to something but we will not accept any underhanded attempts at protecting illegal Hindu foreigners

“Questions can be raised [on the NRC process]. If necessary, in future, we will take whatever steps that will be required,” Assam chief minister Sarbananda Sonowal says this week, hinting at the possibility of legislative action after the NRC list is announced.

For excluded Hindus like Suro, that may be the only hope – but Assamese leaders are in no mood to accommodate them.

“It’s clear the BJP is up to something but we will not accept any underhanded attempts at protecting illegal Hindu foreigners. The NRC is a court-mandated secular process of finding foreigners, we will not allow the government to undermine it through communal means,” says Lurinjyoti Gogoi, general secretary of the All Assam Students’ Union, the powerful youth organisation that spearheaded a six-year nativist movement in the 1980s that changed Assam’s politics forever. “We will fight it politically and legally,” he says.

DEVIL IN THE DETAILS

Suro’s nightmare began in 2005 when police came looking for her on suspicions that she was a “D”, or “doubtful”, voter.

Besides being excluded from the NRC, people can be disenfranchised if India’s Election Commission or the Assam Police Border Organisation report them to the Foreigners’ Tribunal as “D” voters, meaning a potential Bangladeshi immigrant. In all three cases, proof of citizenship is evidence that the person or their ancestors entered India before midnight on March 24, 1971, the eve of the Bangladesh Liberation War from Pakistan.

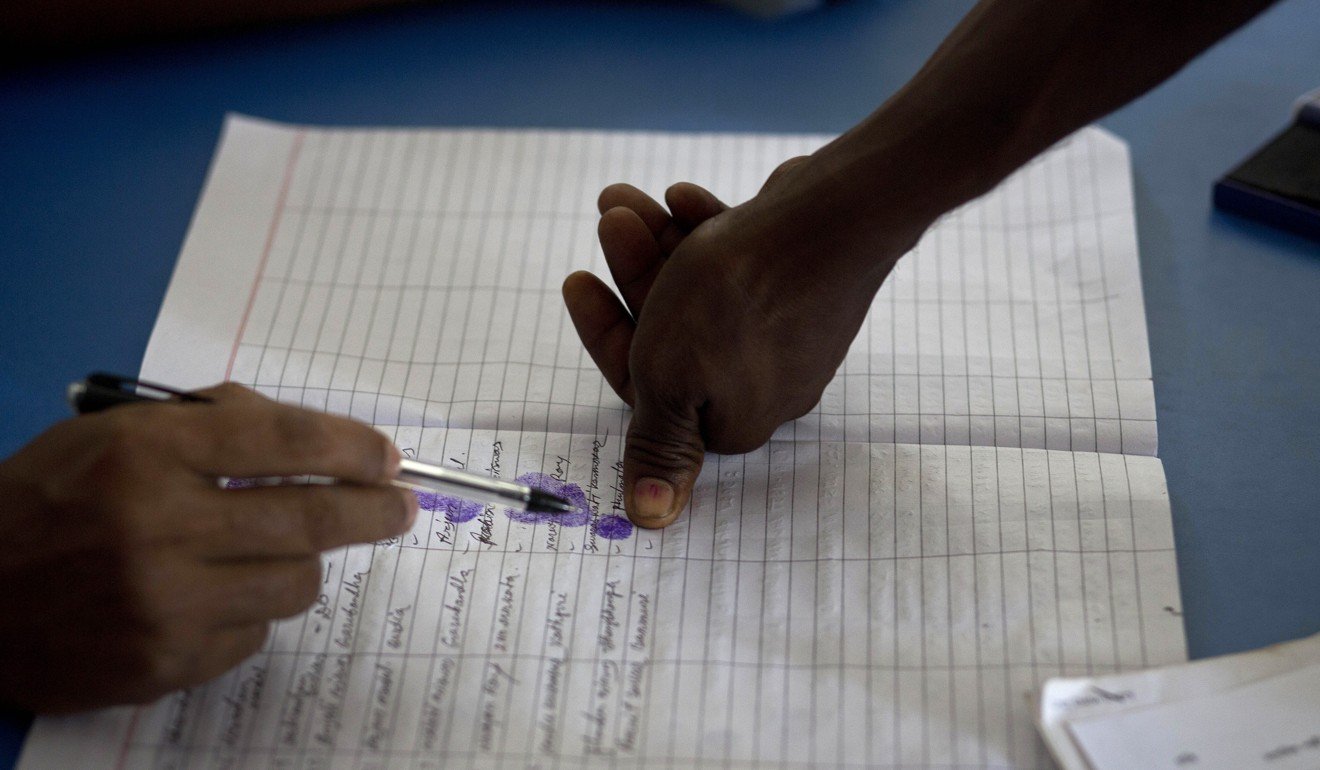

For the NRC, not only do applicants have to submit identity proof for themselves, but they must also establish their relationship with an ancestor who entered the country before the 1971 cut-off date. This entails elaborate “family tree” investigations of what is known as “legacy data”. Establishing one’s “linkage” to the ancestor, or the “legacy person”, requires foolproof documentation.

I will have to die alone, they’ll take me away any day

Suro’s daughter, by establishing her linkage to her father, made it onto the NRC. But Suro had no such documents. Thanks to testimonies from locals, her name had been entered into the electoral rolls, and she was officially an Indian. But new problems arose in 2015, when the government started work on the NRC. When Amiya filled out the form for Suro, she put ajan, an Assamese word for “not known”, as Suro’s father’s name. The authorities took “Ajan” to be a real name. When Suro failed to provide the documents to prove her relationship with “Ajan”, her name was struck off.

Indians told to boycott Chinese goods after Beijing backs Pakistan on Kashmir

“I will have to die alone, they’ll take me away any day,” says Suro, bracing for the spectre of being dragged into a detention centre. In Assam, that is essentially a prison. The province has six so-called detention centres, all housed within prison premises, where someone merely suspected of dubious citizenship can end up sharing space with convicted criminals. There have been several instances of wrongful detention, some triggering national outrage.

Mohammad Sanaullah, who had served in the Indian Army for three decades, spent a week at a detention centre before media attention and the efforts of an activist lawyer got him out. It later transpired that police had framed him. Madhubala Mandal was less fortunate – she spent three years in wrongful detention after police took her for somebody else with a similar name. Poor, illiterate, long abandoned by her husband, and mother to a deaf and mute girl, Mandal, nearly 60, was in no position to challenge her detention in court.

Many have had to serve longer sentences, up to 11 years, before India’s Supreme Court this year ruled that detainees must be freed after three years. There are 1,133 people in detention, including 31 children. Twenty-five have died while being held, the oldest aged 86 and the youngest just 45 days old.

Amrit Das, 70, died in April after languishing behind bars for two years. Suruj Ali, 77, died in June after two years; Basudev Biswas, 58, died in May after four years; and Jabbar Ali, 65, died last October after being held for three years.

Criminalising talaq Muslim divorce in India is overkill

As in Suro’s case, those who know the victims swear they were anything but illegal immigrants, having spent their entire lives in India. And, like Suro, some of their ordeals began with minor errors in documents or failure to sufficiently satisfy the authorities’ demand for paperwork. In Assam today, a forgotten scrap of official paper could save a life – and a typo could take one.

Millions of applicants are illiterate and the Indian bureaucracy is not known for producing or maintaining flawless documents. Even when documents are submitted, allegations abound of arbitrary rejection and partisan tribunal rulings. The reason for this undue haste is the pressure from the government and the country’s highest court to speed up the process.

These tribunals, with about 100 adjudicators who have the power of life and death over millions of people, have little accountability or regulatory oversight and are in effect controlled by the government even though their work is technically overseen by the Supreme Court. Online Indian news site Scroll has accessed records that show the key performance metric for the tribunals is the number of people they can declare foreigners. There have been instances when tribunal members have been dismissed for not declaring enough people foreigners.

THIS LAND IS NOT YOUR LAND

Assam’s quest to cleanse itself of “foreigners” is a reaction to nearly two centuries of inward migration that began with its tea plantations. This started around the mid-19th century, when the British East India Company was seeking ways to narrow the trade gap with China and decided to grow tea in India. Assam was chosen as a viable location to grow tea after a Scottish explorer, Robert Bruce, came across a brew made by a local tribe.

Millions of workers brought in from surrounding regions, even from China, since the 1820s were settled in Assam by the British to work in the tea gardens and clear and farm forest lands. But ethnic Bengalis dominated this migration. Bengali Muslim peasants from adjoining land-stressed regions came in hordes, attracted by easily obtainable and fertile land.

English-speaking Bengali Hindu professionals and officials, who then formed the core of the British administration in India, run from Calcutta, were brought in to administer the newly colonised Assam. The British had just taken over Assam from the Ahom-Tai dynasty that ruled it for 600 years. The province was put under the Raj’s sprawling Bengal Presidency, which at its peak extended from the northwestern parts of modern Pakistan in the west to Penang (Malaysia), Singapore and Myanmar (then Burma) in the east.

India’s dispute with Pakistan over Jammu Kashmir has a loser – New Delhi’s cherished secularism

Throughout British occupation, Assam alternated between being an independent province and an appendage of the Bengal administrative unit. This fluidity made for easy movements of population in the absence of international borders in the region, until India gained independence.

Bengal was subsequently divided into a Hindu-majority West Bengal and Muslim-majority East Bengal. When India was partitioned along religious lines upon independence in 1947, East Bengal went to Muslim-majority Pakistan and was renamed East Pakistan. Along with the giant Punjab and Bengal provinces, Assam was also partitioned and witnessed fresh waves of migration from East Pakistan as a result of the Hindu-Muslim riots that accompanied the partition.

In 1971, Pakistan lost East Pakistan, which became Bangladesh, when its people rose in revolt. In the years leading up to 1971, millions of Bengali speakers, both Hindu and Muslim, migrated to Assam to escape the raging civil war and also to escape the 1965 India-Pakistan war.

But migration did not stop after 1971. Economic hardship and political instability continued to spur Bangladeshis to seek refuge in Assam and elsewhere in India. Climate-related triggers such as extreme weather and salination-induced loss of soil fertility also contributed to the steady exodus out of deltaic Bangladesh, which is prone to cyclones and floods. Gradual Islamisation in Bangladesh was an additional factor, prompting many Hindus who stayed on in Bangladesh after the partition to move to India.

In Assam, anger simmered over this steady inflow and erupted into a students’ movement in 1979 that lasted six years and saw many violent attacks on Bengali speakers.

The bloodiest of them, remembered as the Nellie massacre, took place in central Assam in February 1983 when at least 2,000 Bengali Muslims were butchered by an indigenous mob in an orgy of bloodletting.

The “Assam Agitation”, as it is called, ended with then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi signing in 1985 an accord with the All Assam Students’ Union. The March 1971 cut-off of Indian citizenship was part of that agreement, but politicians allegedly continued to allow new migrants to settle in return for electoral allegiance.

What happened to India’s disappearing Chinese migrants?

“Successive Congress governments helped Muslim migrants to settle to use them as a vote bank, giving them property and voting rights,” says Nava Thakuria, secretary of the Guwahati Press Club, echoing a common Assamese perception.

Estimates of the number of illegal Bangladeshi migrants in Assam vary widely, from thousands to millions, depending on who you are talking to. There is no reliable data and the numbers can vary even between different levels of the government.

“Ninety per cent of the cases I am dealing with pertain to people who have been here forever. Where are these millions of Bangladeshis you keep hearing about?” says a lawyer who did not want to be identified, to protect his clients. “These days, anybody who is a Muslim, even an Assamese Muslim, is a Bangladeshi. And anybody who speaks Bengali, whether Hindu or Muslim, is a Bangladeshi.”

But officials in the highest echelons of power in India have been warning of large-scale illegal migration in Assam and the risk of demographic changes, a fear that resonates strongly in Assamese society. Persistent concerns over migration led to the formulation of an NRC for Assam when the Congress party was in government. The BJP inherited the idea with Modi’s rise to power in 2014 and made it one of its key deliverables. As the process of finding illegal immigrants hits high gear, the NRC now threatens to unleash havoc as it tears apart families and communities.

BROKEN HOMES

One afternoon two years ago, a local policeman came to meet Sujit Bala, a false-ceiling maker. Bala, 47, was contesting in court a “D” voter notice served by police. The officer asked Bala, a Bengali Hindu, to accompany him to the station to sign some papers.

“The moment he set foot in the police station, he was arrested and then moved to a detention centre in Goalpara, four hours by train from here,” says his daughter, Puja, 24. There was no tribunal ruling. Bala’s family could theoretically contest his incarceration in higher courts, but they are too busy staying alive.

No one in the family, except Bala, has ever worked for a living. Now Puja and her mother, Sanjukta, sift plastic in back-breaking 10-hour shifts at a recycling plant. Each makes about 200 rupees (US$3) a day.

We can’t even afford to visit him, how are we going to find a lawyer?

Bala’s son was pulled from school when savings ran out, and now works as a casual worker at construction sites. Bala’s own home is an abandoned skeleton of brick walls on the western fringes of Guwahati. He had just started building it when he was taken away. The three live in a dark, semi-built room at the back – they cannot afford electricity.

Bala ran away from the adjoining Indian province of West Bengal in his early teens and ended up in Assam. He has school certificates from West Bengal, which make him a bona fide Indian. His wife Sanjukta is Assamese, and the two children have birth certificates.

“He cries every time we go to visit him. He pleads with us to get him out, but what can we do?” she says, laying out Bala’s identity documents on a chair. “We can’t even afford to visit him, how are we going to find a lawyer?”

Every trip costs the family about 700 rupees by way of train tickets and meals, not to mention the loss of a day’s wages.

“The government we voted for has taken away my father. They have killed us,” Puja says.

POETIC INJUSTICE

Write

Write Down

I am a Miya

My serial number in NRC is 200543

I have two children

Another is coming in the next summer,

Would you hate him

As you hate me?

Rarely does poetry invite police action in democracies. But in response to complaints against this poem by Kazi Sharowar Hussein last month, the Assam Police filed a case against 10 activists who have been writing about the discrimination and pain Bengali Muslims face in Assam. Written in their native Bengali dialects, rather than Assamese, this literary genre has come to be known as “Miya poetry”.

The word miya is used by Muslims in South Asia to mean “gentleman”, but has been reduced to a pejorative in Assam, where it now denotes a Bengal-origin Muslim immigrant. The Miya poets, by reclaiming the word and their Bengali Muslim roots, have made these resistance poems the latest flashpoint of a centuries-long culture war.

The colonial government in 1836 declared Bengali as the official language of Assam. It would take nearly four decades to reverse the decision, but the linguistic enmity it triggered would continue to haunt the province. When Assamese was made the official language in 1960, Bengali speakers erupted in protest. The government had to make room for Bengali as an official language in some districts.

The controversy over “Miya poetry” reflects the Hindu-Muslim religious polarisation that has come to define Indian politics of late under the Modi administration. But in Assam, it is also an odd inversion of an old culture war. Though it was the Bengali Muslims who embraced an Assamese identity while Bengali Hindus resisted it, the Hindus are being courted by the ruling BJP and assured of their citizenship while the Muslims now find the government seeking to evict them as Bangladeshi aliens.

Would-be Shah Rukh Khans beware: surrogacy bill spells end for India’s US$2 billion ‘rent-a-womb’ industry

The percentage of Assamese speakers in the province went up from 31.4 per cent in 1931 to 56.7 per cent in 1951 largely because Bengali Muslim peasants identified themselves as Assamese speakers after the partition. A social media campaign called chalo paltai, or “let’s change”, is calling upon Bengali speakers who identified Assamese as their mother tongue in earlier censuses to go back to Bengali in the 2021 census. For the ruling BJP, the migration problem is about religion, a simple Muslim-Hindu binary. For the Assamese, it is about language and identity, in a province that has 55 linguistic communities.

Nobody imagined it would be so horrendously complicated and put common people through such an ordeal

“When the NRC was launched, everybody in Assam thought it would end the decades-old wrangling about natives and foreigners. Nobody imagined it would be so horrendously complicated and put common people through such an ordeal. The BJP and the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the ruling BJP’s right-wing parent organisation] seized the opportunity to harass Muslims and stoke communal politics,” says Hiren Gohain, a literary critic and Assam’s most famous public intellectual.

“The RSS-BJP is out to deepen the distrust and rift between the Assamese and immigrant Muslim populations, and then turn on Muslims.”

But several Hindu Bengali groups say they are the ones under siege in Assam. A recent memorandum by the All India Bengali Organisation (Aibo) sent to Home Minister Shah complains against the “atrocities on the Indian Bengali community in Assam”, detailing the many ways the Assamese officials have been conspiring to evict them.

For many in the community, like Aibo’s Assam president Ashis Das, the possibility of a legal manoeuvre to naturalise Hindus is hardly a source of relief. “First, it is not clear whether a law change makes one a full-fledged citizen or merely somebody who can apply for citizenship. Besides, we are the sons of the soil, why should we have to struggle to prove our citizenship? If Bengal-origin Assamese identify as Bengalis, and Hindu and Muslim Bengalis unite, we will be the dominant power in Assam.”

But the chances of such a dramatic alliance may be slim, largely because of the long history of religious animosity between Muslims and Hindus – even if they both speak Bengali and are now seen as Bangladeshi. Muslims dominate 35 of Assam’s 126 provincial Assembly seats, making them central to mainstream politics and reluctant to align with fringe forces. Most Muslim community leaders also believe the Hindus will lose the will to fight once the BJP finds a way to accommodate the Hindus sieved out by the NRC. The same belief still makes many in the Bengali Hindu community stick to the BJP.

FRIENDS LIKE THESE

“Detect, delete and deport all illegal foreigners – this was the clear pledge of the Assam Accord. The government is now trying to dance around it,” says Gogoi of the All Assam Students’ Union. In the run-up to the recent elections, the BJP was equally emphatic and promised to “throw out” the “Bangladeshis”.

Pakistanis in Hong Kong condemn Modi’s move to strip Indian-held Kashmir of autonomy

But Bangladesh – the world’s most densely populated country, straining under more than a million Bengali Rohingya refugees, who are also Bengali speakers – refuses to be any part of the NRC. Dhaka’s default position has been that it is India’s “internal matter”. Curiously, India’s External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, said pretty much the same thing while touring Bangladesh this week. As Assamese leaders like Gogoi point out, this indicates the government has not put any mechanism in place for deportation.

While Bangladesh has obvious reasons for not being interested in India’s rejects, New Delhi also cannot afford to push Dhaka to accept large-scale deportations. Bangladesh is one of the few countries India gets along with in the neighbourhood, where China’s influence has been rising rapidly in recent years. From ports to highways, China has been pouring billions of dollars in infrastructure projects in Bangladesh as well. Still, for New Delhi, Bangladesh’s secular Awami League government is a good hedge against the Islamic opposition parties ranged against India.

By keeping the radical Islamic elements in check, the government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed secures the safety of the remaining Hindu population in her country, creating the incentive for them to stay on rather than migrate to India. In return, India looks the other way as Wazed wins election after election by locking up her opponents in jail.

“The NRC is making it very difficult for Hasina. This constant demonisation of Bangladeshis is turning public opinion against India, giving anti-India forces in the opposition a handle,” says Subir Bhaumik, author of Troubled Periphery: The Crisis of India’s North East. “Bangladeshis are also deeply scared that the havoc caused by the NRC will cause a tide of reverse migration from India that the tiny country won’t be able to handle.”

BETWEEN A FLOOD AND AN EARTHQUAKE

The sun is about to set. Mongoldoi high school, 75km north of Guwahati, usually begins to empty this time of day. But it is heaving with people – refugees from Bandiya Char fleeing a raging flood. Every year, the river swells after the monsoons, affecting millions. This year has been no different. It has claimed more than 60 lives, submerging 4,000 villages in 28 of the province’s 33 districts.

The flood is particularly punishing for the people on the chars, or riverine islands, in the mighty Brahmaputra River that originates in Tibet and runs through Assam. The chars are fertile, but vulnerable to the caprices of nature. No one who could help it would live on a char, so they are home to the poorest and the weakest. Most live below the poverty line and 80 per cent of them are illiterate.

A fourth of Assam’s population is estimated to live on chars. Every time the flood hits, the char people, mostly Muslims, flee with whatever they can salvage to the nearest highland and wait for the river to calm down. Then they go back again and rebuild their homes and lives.

Bollywood teaches more about Kashmir than India’s schools

The chars are also believed to be home to many who fled Bangladesh or erstwhile East Pakistan for a better life in India. The natural river boundary, cross-border networks of kinship and poor border control make the chars easily accessible to migrants. It also makes char inhabitants prime suspects as illegal migrants, even those who have lived there for decades. This year, the flood is the least of their problems.

You have to go to a tribunal hearing even if you die

Abdul Haq, 77, and his family fled Bandiya Char in a boat with their most precious belongings – eight cows, six hens, one goat, bedclothes, grain, clothes and some cooking utensils. And, most importantly, their documents. Three of his grandchildren were not on the last NRC list. This means more runs to the tribunals. The day Haq landed in this makeshift flood shelter, he was due for a tribunal hearing 24km away at 9am. The government did not bother to reschedule despite the floods. Haq had to rush to the tribunal with the kids soon after steering his family to the safety of the high school.

“You have to go to a tribunal hearing even if you die,” says Haq. “I grew old here, my name is on the 1966 voter rolls, and they call my descendants Bangladeshi.”

This phenomenon of exclusion of one or two members of a family while the others are declared citizens is widespread. Further north, in the Badhir Char village near Kharupetia town, almost every household has a member or two missing from the NRC. More built up than a regular char, Badhir is less vulnerable to floods, but still some roads have caved in. The whole area was under knee-deep water just a few days ago.

In times like these, any man getting off a car with a notepad in his hands is a source of hope. Crowds gather, a seat and water are offered, and then come the complaints and the entreaties. “Saiful Islam’s two sons, Anwar Hussain’s wife, Akbar Ali’s two brothers … why aren’t they on the list? Please do something, sir.”

It is Mujibar Rahman’s turn. He says he is on the NRC list, his wife is not. Of his six children, daughters Muksida and Murshida and son Hilaluddin are not on the list; the others are.

Hilal, 12, is older than the other two, and a little shy. It is difficult to imagine how he will handle the grilling by tribunal adjudicators demanding the correct names of his forebears. If he says the names wrong in the family tree test, he puts the whole family at risk.

I try to make some light conversation with the children to lighten the mood. Muksida and Murshida seem more interested in running around a nearby tube well than having a conversation. I turn to Hilal.

“So they are saying you are a Bangladeshi? Do you know what Bangladesh is?”

He lowers his head, embarrassed that he does not know.

“OK, then tell me, what is India?”

Hilal raises his head and smiles confidently. He has an answer. “Assam,” he says. ■