Where Instagramers and Taliban play in Afghanistan

Ishkashim is a bright spot in Afghanistan’s long-suffering tourism industry as it attracts those seeking superb selfies. And it’s perfectly safe – just ask the locals

“I ’m just crossing over to get a picture!” Tomas, a Czech Instagramer, proclaims as he forces me to take his photo at the Afghan border.

He’s one of hundreds of Westerners who will cross the remote Ishkashim border, separating Tajikistan and Afghanistan, this summer in search of adventure, untamed wilderness – and selfies.

Ishkashim is a small district in Afghanistan’s far northeast Badakhshan province that serves as the gateway to the famed Wakhan Valley – home to some of the world’s most remote communities and best trekking.

Wakhan has historically courted only the most extreme travellers. That is changing, as day trippers and more seasoned travellers seek out a taste of Afghanistan in one of the few parts of the country where their safety is all but guaranteed.

Open-door policy

Like many tourists trawling Tajikistan’s Pamir Highway, the temptation to cross into Afghanistan is too great. I picked up my tourist visa in Khorog, Tajikistan – a three-hour drive from the border crossing – and set off to explore what has been widely called the country’s safest, most accessible corner.

‘ATM Modi’ squirms in Trump’s Afghan embrace

In an acknowledgement that tourism is vital to Ishkashim and its surroundings, Afghan authorities have made visiting as easy as possible.

The Afghan Consulate at Khorog is known in adventure-tourism circles as the best place to receive a visa, with a turnaround time of just 10 minutes for some travellers.

I received my visa within the hour from an official who claimed to have issued 15 tourist visas the previous day. The brief delay was caused by a group of British pensioners who, as part of their cycling trip along the Panj River, were planning a day trip to Afghanistan.

At the border, which only opens for two hours each morning and afternoon, tourists queue, waiting to cross. It is here I meet Tomas, who is determined to get his selfie on Afghan soil.

I asked Tomas if he felt the same apprehension as I did, and asked why he couldn’t just take his selfie from the border. “The city is much better for a photo,” he said.

We cross in tandem, brushing shoulders with Australian, Dutch and German tourists who are returning to Tajikistan after their own adventures to the Wakhan.

“We have tourists cross every day during the summer,” an Afghan border guard says as he stamps visas.

A tentative peace

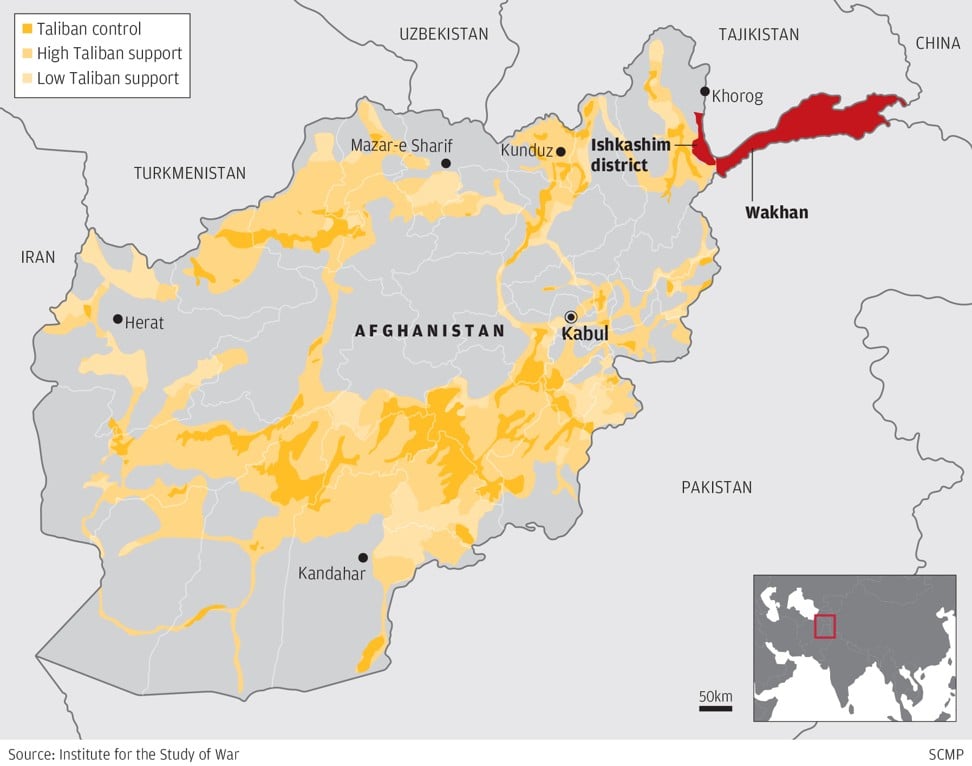

Though Ishkashim enjoys relative security, travel to the district still carries a modicum of risk. In May 2017, a resurgent Taliban attacked the district before being repelled.

Local authorities claimed they had removed 20 Taliban positions from within the Ishkashim district alone.

Ishkashim has since been free of such incursions. But elsewhere in Badakhshan province – and across the country – a resurgent Taliban is evident. With strongholds in neighbouring Zebak district – just a few miles from the Tajikistan border – the Taliban appear to have consolidated their positions in Badakhshan.

In Afghanistan, Putin courts China in search of ‘another Syria’

That the Taliban has made considerable gains in Badakhshan – a province it never controlled, even during its five years in government – demonstrates the militant group’s rising influence since a draw down of foreign troops in 2014.

Sadikalar, 35, is a member of the Afghan National Police who is stationed at the border and can be hired as a guide. I first approached Sadikalar after receiving dire warnings from a disgruntled local as I entered Afghanistan.

“I’d leave first thing tomorrow,” the elderly Afghan – who was travelling on a Canadian passport – warns me. When pressed for details, he says a Taliban attack would happen in the coming days.

Sadikalar laughs off the old man’s scaremongering.

Pakistan waves a bin Laden olive branch at US, as Chinese cash loses shine

“No, no,” he says, reassuringly. “You will be safe here. Please, come and stay with me. I will show you Ishkashim.”

As we explore the district in Sadikalar’s mid-90s Toyota Corolla, one of the few cars in the district, on dirt roads marked with potholes – much worse than what’s across the border in Tajikistan, we pass verdant green fields and shepherds on donkeys.

At times, Sadikalar pauses to highlight a local feature: a school, hospital, or barracks. He also notes the proximity of his enemy.

“The Taliban are just 6km away. Just over that mountain”, he says, with a wry smile, pointing towards a small hill near our position.

Populated largely by moderate Ismaili Muslims, Ishkashim is a district where extremism has long been resisted, and the Taliban have never truly taken hold.

In Ishkashim bazaar, most men are clean shaven. In homes and in fields, women and girls wear only modest headdress. Some women even hold a scepticism of religion, while others confess a fondness for the wine and Russian vodka that sometimes makes its way across the border.

Rohingya or Afghan? In Indonesia, a tale of two refugee groups

Even during the Taliban’s control of Afghanistan, from 1996-2001, only four Taliban envoys ever made it to Ishkashim, according to Sadikalar. At the time, Badakhshan was a stronghold of the Northern Alliance, a collection of groups opposed to the Taliban.

Cut off

Despite its reputation as a safe haven, the impact of the Taliban on Ishkashim is easy to see.

Sadikalar drives to meet some of his relatives in small village a few kilometres from Ishkashim bazaar. There, in an open-plan, Pamiri-style home Ruboda, a village elder, offers a snack of green tea and bread – a display of hospitality that is common here.

She is quick to denounce the Taliban.

“I lost both my husband and son to Talib”, she says, sitting next to her two granddaughters who are glued to her side. Like Sadikalar, both were Afghan National Police officers, who had lost their lives to Taliban in fighting outside Ishkashim district.

More overt is the Taliban’s economic impact.

Ishakshim’s unique geography renders it largely isolated from the rest of Afghanistan. Major roads connecting the district run through Taliban-controlled territory, limiting its commercial engagement with the rest of the country.

Pakistan’s stance on militants alienated the US. Is China next?

As a result, Ishkashim and Wakhan’s economy rely almost solely on tourism, and foreign aid projects that help facilitate such tourism, most run by the Aga Khan Foundation and financed by Japanese, German and Canadian governments.

The isolation causes prices to be inflated for tourists. The few-hour ride from Ishkashim to the start of Wakhan Valley hiking paths is fixed at US$400. A similar journey on the Tajik side of the Panj river, in contrast, could be as little as US$10. Homestays cost between US$25-30 per night, about double the price across the river.

‘It’s only bad when they attack’

Once considered among the most stable areas in Afghanistan, northeast Badakhshan lost that reputation after the May 2017 attack.

“We used to have more tourists three or four years ago”, says Idi Muhammed, a shopkeeper and English teacher.

“I think people are scared, because of what happened last year. And because less people are coming, the guest houses are closing down”.

But despite the tenuous security situation, he stresses the safety of the region. “You don’t need to worry in Ishkashim – you are safe here,” he says. “Afghanistan is an incredible place every day of the year. It is only a bad place when they [the Taliban] attack”.

As Pakistan loses support, it should lose the pretence on cross-border terror, too

Sadikalar is quick to pile on to Muhammed’s assurances.

“There are 700 police in Ishkashim,” he says. “No Taliban would dare attack here.”

In the bazaar, the centre of the district, the military and police presence is overwhelming. While the district feels rather normal – almost mundane – in parts, the heavy security presence serves as a reminder that the peace here is a delicate one and must be protected.

Hope shattered

On my final night in Ishkashim, Sadikalar invites a group of English-speaking locals to join us for dinner. Over bread, aniseed-infused green tea, and chicken rice, Rafi, a 33-year-old public servant running for office, shares his campaign pitch.

“The most important things for Ishkashim and Wakhan are growing tourism and [ensuring access to] education for everyone,” Rafi says. “But we [first] need to guarantee security.”

As Rafi speaks, a television in the restaurant broadcasts images of Taliban fighters and Afghan soldiers taking selfies together during the Eid ceasefire last month.

Sadikalar’s eyes go wide at what he sees: the first genuine ceasefire since the US invasion. He was sanguine about his government’s plans. “Maybe this can last.”

Two days later, the Taliban broke the ceasefire. A new fighting season had begun. ■