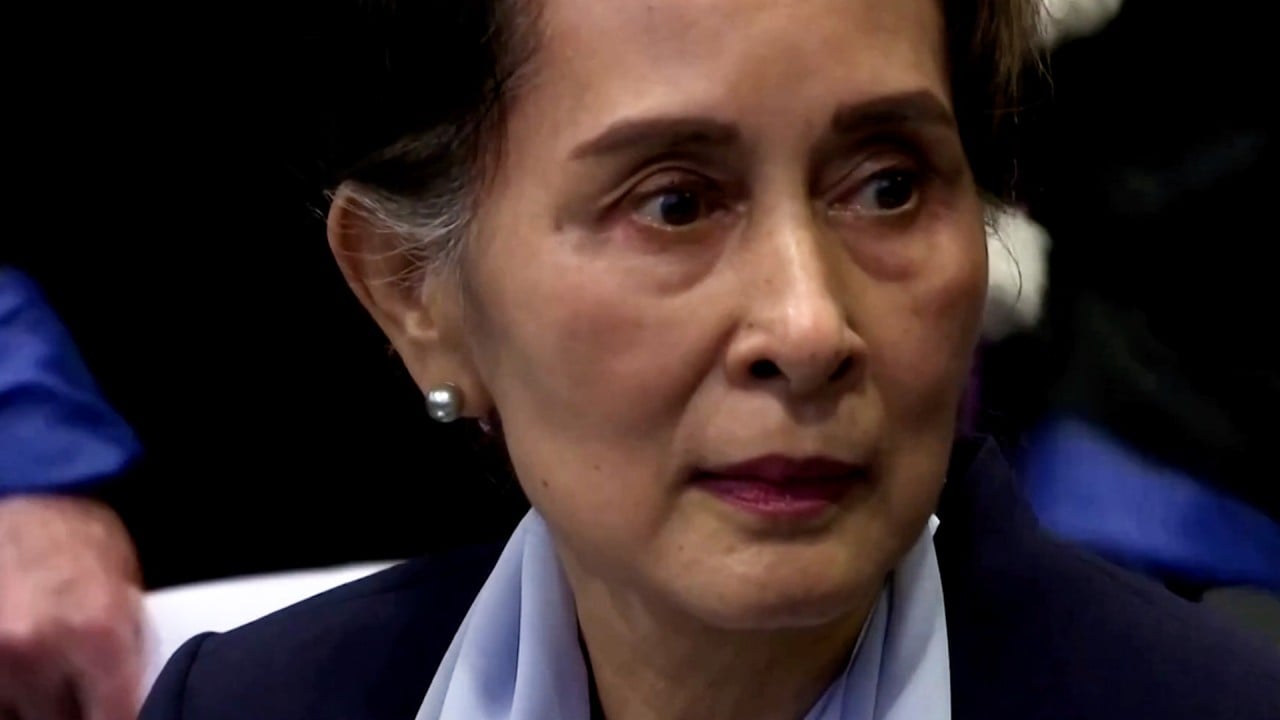

Is Myanmar junta’s partial pardoning of Aung San Suu Kyi a ‘cynical ploy’ for goodwill?

- Analysts say the partial pardon is the junta’s attempt to ‘buy some time’ in reducing international pressure to restore order

- The move comes as views against the junta start to harden, over its air wars, and as it steps up its campaign of terror against the population

The pardon means six years will be shaved off the democracy icon’s 33-year jail term, and came as part of an amnesty under which more than 7,000 prisoners were freed across the strife-torn country.

Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, DC, said the pardoning of Suu Kyi on trumped-up charges was “nothing more than a cynical ploy by the junta to elicit some goodwill”.

It comes as international views against the junta are hardening over their air wars, and amid the intensification of the campaign of terror against the population, Abuza said.

“They are simply hoping that enough states will view this as a moderation of their stance and a sign that they are looking for an off-ramp, when all they are doing is trying to buy some time for themselves,” said Abuza, who focuses on Southeast Asian politics and security issues.

In recent months, the military junta has increased the number of deadly air strikes against the growing armed and civil resistance to its rule; rights groups have said that most of the targets and victims were civilians.

Data from the US-based NGO, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, found that over 40 military strikes were reported in June alone, more than at any other month this year.

The air strikes had reportedly burnt down entire villages, destroyed clinics and hospitals, and claimed the lives of thousands of civilians.

Hunter Marston, a Southeast Asia-focused researcher at the Australian National University, said the junta was trying to divide the resistance and weaken international pressure “to demonstrate real changes”.

By reducing Suu Kyi’s sentence, Marston said the junta was likely seeking to create fractures within the National Unity Government (NUG) – formed by lawmakers ousted during the 2021 coup launched by the military.

The junta hopes to “encourage moderates in the National League for Democracy (NLD) who may be willing to work with the junta to question the resistance movement”, Marston said, referring to the democratically-elected ruling party ousted by the military.

Marston said Suu Kyi’s partial pardon fits with decades of junta practice, whereby the former state counsellor would be released and rearrested “to suit its political purposes”.

“This is no different,” Marston said.

Describing the pardon as taken “out of an old playbook in Myanmar”, Sean Turnell, a non-resident fellow at the Sydney-based Lowy Institute, wrote that the junta was weakened by its inability to surmount the opposition to its rule.

“Running out of foreign exchange, of troops to sacrifice, and of ideas beyond base instincts, the junta is attempting an old public relations game and hoping an exhausted and distracted world might fall for it,” Turnell said in his institute’s publication The Interpreter.

Turnell added that “real change is possible in Myanmar, but it will not come from applauding meaningless gestures, as attractive as they might be as ‘clickbait’”.

Writing on social media, Bilahari Kausikan, Singapore’s former ambassador-at-large, said it might be possible that Suu Kyi had started negotiating with the military as both “share a common interest in cutting out the NUG from any settlement”.

“Suu Kyi because she wants her NLD back in power and the military because it is fighting the NLD’s military arm, the People’s Defence Force,” he said.

“Suu Kyi and the Tatmadaw have more in common than either would care to admit, not the least of which is a sense of entitlement to rule and a tendency to treat the people of Myanmar as subjects not citizens,” Kausikan said. “But precisely because they are so similar it is hard for them to get along and if indeed they are negotiating, don’t expect a quick result.”

On Monday, the junta postponed an election promised by August this year and extended a state of emergency for another six months.

Earlier this year, the State Administration Council (SAC), or the government formed by the junta, said they could not hold elections until a census was conducted in October 2024.

Abuza said this was “a tacit admission” that the ruling junta did not have sufficient control over large swathes of their territory to hold elections, adding that for the SAC to try to hold elections, “as shambolic as they would be, would be a humiliation for the junta”.

Marston said an election was unlikely in the next six months to a year, as “even a partially inclusive election would require an end to fighting” in much more of the country than currently exists.

“It would be virtually impossible to extend such polls to most areas of Kachin, Chin, Sagaing and Karen states, where fierce fighting is occurring,” Marston said, adding that the junta was more likely to use the prospect of elections as a bargaining chip with outside powers to alleviate pressure and grant it greater legitimacy.