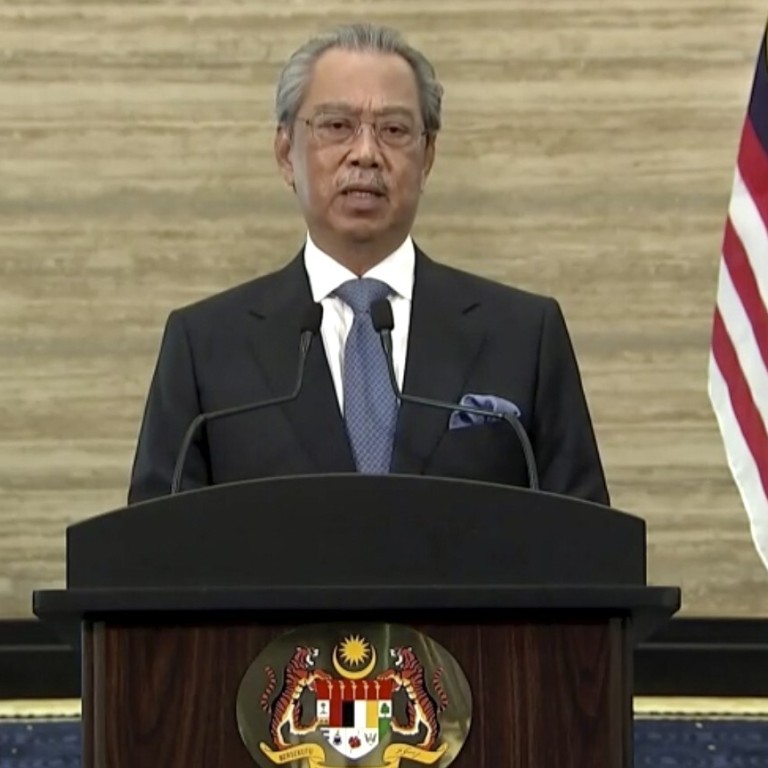

Why Muhyiddin’s government and Malaysia’s fragile status quo won’t last much longer

- Malaysia’s shifting alliances, past betrayals and future electoral prospects make for a complex and unstable situation

- The February coup may have been propelled by Muhyiddin’s ambition but racially tinged divisions played a part and could determine what comes next

As much as the February coup was propelled by Muhyiddin’s ambition, racially tinged divisions also played a part, and could again determine the shape of any future government.

Mahathir and Muhyiddin, both former members of Umno, disagreed about whether the party should be allowed to return to government. Mahathir was determined to block Umno from the centres of power while Muhyiddin cultivated a new partnership.

It enabled Muhyiddin’s new coalition to claim a four-seat majority in Malaysia’s 222-seat parliament. But the alliance between the three majors partners – Muhyiddin’s Bersatu, Umno and the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) – seems unlikely to last much longer.

Bersatu and Umno both seek to dominate. Umno’s main complaint has been that although it has 39 seats compared to Bersatu’s 31, members of Muhyiddin’s party were rewarded with the most important ministerial portfolios.

The other source of conflict is the fact Bersatu won only six of its 31 seats in the 2018 elections. Another 15 seats came through defections from Umno – seats which Umno is eager to recontest. A further 10 seats came from Azmin’s faction after he left PKR to join Bersatu following his rift with Anwar.

After Sabah election, Muhyiddin sitting in pole position to hold off Anwar

More recently, the fallout from last month’s Sabah state election could further undermine Muhyiddin’s fragile PN coalition. The election was an unnecessary distraction for Muhyiddin after he sought to induce enough defections to oust the state government led by Shafie Apdal, who refused to support Muhyiddin’s coup earlier this year. His plan backfired when Shafie managed to dissolve the assembly, triggering the election.

Shafie is now free to pursue federal politics, having campaigned on a powerful “Unity” message. He has previously been discussed as a prime ministerial candidate – a possible alternative to Mahathir and Anwar for the opposition.

It remains unclear how Anwar has obtained his proclaimed majority but the DAP, a key plank in his coalition, remains adamant it will not accept a partnership with Umno while it is led by Zahid Hamidi, the party’s president, and Najib, who remains influential.

History may offer some clues: whether Anwar has the numbers or not, his claim weakens the incumbent prime minister. Anwar made similar statements before, in September 2008, undermining Abdullah Badawi, who was prime minister at the time. His rivals within government, including Najib and Muhyiddin, confronted him and demanded he cede the finance ministry portfolio to Najib. A week later, Najib and Muhyiddin pressed Abdullah again, this time forcing him to announce his retirement, effective the following year.

Explainer: How 1MDB corruption scandal changed Malaysian politics

Now, in 2020, it is again unclear whether Anwar indeed has the numbers to form government. It is hard to foresee how Anwar’s coalition partners – particularly DAP but also Amanah – would be willing to cooperate with Umno. It is also unclear how the mainstream faction of Umno would be prepared to work with DAP, having demonised them for the past 12 years. Nonetheless, Anwar’s claims dial up the pressure on Muhyiddin.

For now, Muhyiddin can still rely on the support of PAS – the third major partner in his coalition. The Islamist party aims to retain control over seats in Kelantan, Terengganu and northern Kedah, more easily achieved by aligning with Muhyiddin than by hitching its cart to Umno, its main rival for the past 60 years.

Muhyiddin could yet continue to rule with a minority government if he manages to split Umno into two, provided his opponents are unable to reach a consensus. Alternatively, Muhyiddin could make further concessions to Umno to keep them in his coalition, perhaps by appointing a senior Umno leader as deputy prime minister. However this would also leave him vulnerable, effectively making him hostage to Umno.

Admittedly, Umno is not a coherent force. Its MPs are divided between Najib and Zahid on one side, and Foreign Minister Hishammuddin Hussein with his minority faction on the other. Beyond that, Deputy President Mohamad Hassan, who does not have a parliamentary seat, has urged Zahid to remove Umno from Muhyiddin’s governing PN coalition. Science Minister Khairy Jamaluddin and factional leader Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah also wield influence but are not publicly aligned.

Gabungan Parti Sarawak, the Sarawak-based coalition that remains allied to Muhyiddin, looms as a wild card. They hold 18 seats in federal parliament, making their support potentially decisive.

Muhyiddin’s more popular than Mahathir but not with Malaysian-Chinese

Malaysia’s complex alliances, with their scars of past betrayals, internal party divisions and future electoral prospects are a recipe for instability. And these tensions appear destined to assert themselves in coming weeks.

Umno will hold its divisional meetings before parliament sits for the budget session from November 2. Failure to pass the budget would likely translate to the collapse of Muhyiddin’s government.

Unless he can find a way to strike some grand bargain with Umno or drive a wedge between its various factions, or agree a ceasefire with the opposition, a snap election seems increasingly likely, even if no one can confidently predict its result.

Liew Chin Tong was Malaysia’s Deputy Defence Minister from July 2018 to February 2020. He is a member of the Democratic Action Party’s Central Executive Committee.