Modi is facing a perfect storm in Gujarat. Can he weather it?

Caste alienation, a resurgent opposition and popular discontent challenge Indian leader in his home base. His continued grip on power will depend on whether he manages to stand his ground

A round of ice cream is passed around the hall to mark the event. There’s a cake too – it’s the local unit leader’s birthday – and a “happy birthday to you” singalong by party workers.

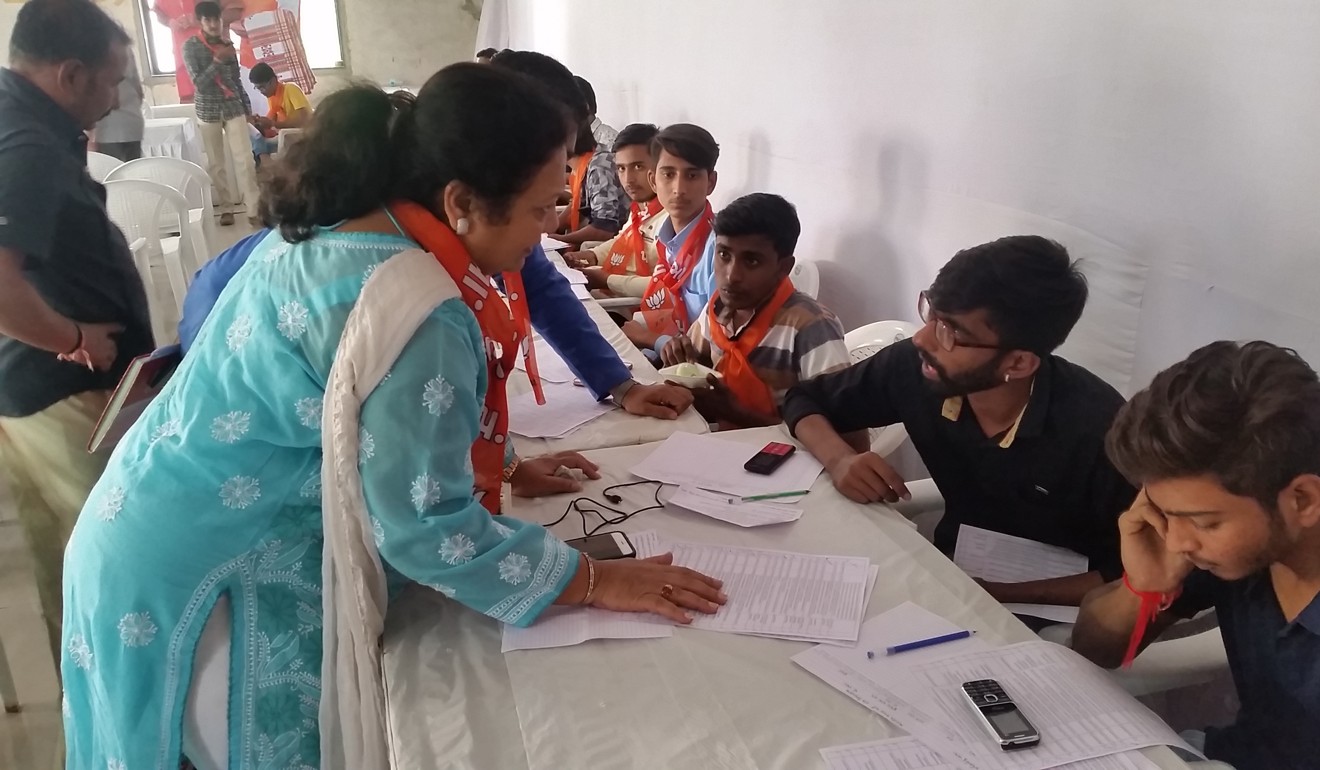

Speeches and festivities over, Darshana Jardosh, the member of parliament from Surat, gets down to business. Karanj is one of the seven Assembly seats that make up her parliamentary constituency. It’s not difficult to see why the 56-year-old Jardosh has won two elections back to back. Powerful yet approachable, she exudes clinical efficiency and infinite energy – a bit like her Hindu nationalist party, that has ruled Gujarat for the past 22 years.

Jardosh takes stock of the newly set up social media cell, then takes a tour of the two rows of callers along the sides of the hall. Two fresh-faced college students volunteering for the BJP give her a rundown of the day’s work so far. It’s mostly going well, they say. She seems pleased and moves on to the next row.

Withdrawal symptoms: cash is still king in India, Modi not so much

The BJP during the 2014 general election launched a nationwide campaign asking people to dial a given number to register support, she explains to me. Some 100 million calls were received, of which 1.1 million were from Surat and about 50,000 from Karanj. The party had stored the numbers in its database then and is now reconnecting with the callers. “We are inviting them to volunteer and also asking them for feedback. Once we have contacted all those on the list, we’ll call other registered voters to rally support.”

Organisational efficiency like this, and his consolidation of the Hindu vote, helped Modi’s successful reign as Gujarat chief minister for 12½ years, propelling him to national leadership in 2014. The party has since evolved into an unbeatable election machine nationwide, churning out victory after victory in regional polls. His charisma and the opposition’s atrophy meant that, not too long ago, Modi’s place at the top of India’s political pyramid was unassailable. He still retains formidable support, but over the past year his standing has suffered. The mighty machine is at serious risk of sputtering, along with the economy that he had promised to fix but has got worse on his watch.

This Gujarat election is 67-year-old Modi’s chance to prove to the country that he retains the people’s confidence. A convincing win here would silence critics and defuse a budding opposition build-up. Gujarat will decide if he keeps the reins of India for another five years when the country holds its next general election in 2019.

MONEY PROBLEMS

Modi’s sudden decision to withdraw high-denomination banknotes last year in an attack on unaccounted wealth wreaked havoc on India’s cash-driven economy. Even before the economy had fully recovered from that shock, this July he hastily unrolled a poorly designed and cumbersome nationwide goods and services tax (GST) that has severely hurt businesses.

India’s ‘simplified’ tax scheme is anything but simple

Gujarat, with its legions of entrepreneurs, is bleeding. Here in Surat, one of India’s biggest textile hubs, supply chains froze up as a result of a new tax on textiles. Many of the city’s 700,000 looms closed, traders shut shop and marched in protest. The diamond industry, Surat’s other big driver, is hurting too. Smaller diamond businesses in this city, where 90 per cent of the world’s diamonds come to be cut and polished, are furious at the new 3 per cent tax slab on polishing and the heavy compliance burden as a result of a complex filing system in a clunky online procedure.

“The government should have waited to put the software and system in place, and discussed it with the industry,” says Dinesh Navadiya, regional chairman of the Gems and Jewellery Export Promotion Council. The council’s trade data show gems and jewellery exports fell 10 per cent between April and September.

The promise of reviving an economy slowing under the previous Congress government was Modi’s main electoral plank in 2014, built on his helming of the high-performing Gujarat economy. But from 9.1 per cent in the first quarter of last year, the Indian economy slowed for six straight months to grow at just 5.7 per cent in the June-September quarter. It edged up to 6.3 per cent in July-September, but is still far below the 6.9 per cent bottom India hit during the 2008-2009 global recession.

Modi had promised to create 10 million jobs. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy estimates that some 9 million jobs were lost in the past year while the International Labour Organisation expects unemployment in India to increase from 17.7 million last year to 17.8 million this year and 18 million in the next.

Note ban: will it make India, or break Modi?

He is also grappling with a deepening rural distress in a country where 70 per cent of the people live in villages and nearly half the 1.3 billion population depend on farming. Farmers blame him for not keeping his election promise of ensuring a minimum profit of 50 per cent above the cost of production.

Doubling farm incomes by 2022 was his key election promise, but falling crop prices and rising prices of inputs like water and power make that a pipe dream. In Gujarat, farmer discontent has been compounded by extensive land acquisition by a business-friendly state government keen to facilitate industrial growth.

THE FIGHTBACK

The opposition Congress has been smartly tapping into the cumulative anger. Rahul Gandhi, the scion of India’s foremost political family, has been leading the charge with an energetic campaign.

Not far from the new BJP office in Karanj, people have been filing into the Jal Kranti sports ground in the Varachha assembly segment since evening for a rally Gandhi will address. By the time he starts, around 9.30pm, the ground has filled up, with crowds brimming over to the roads alongside. Courting of big business at the cost of agricultural land, lack of crop insurance, GST, currency ban – Gandhi is hitting all the right notes. “The World Bank says India has become more business-friendly,” he says, referring to the country’s 30-rung jump in the bank’s Ease of Doing Business ranking. “Really? Did they ask Surat’s traders?” The crowd laps it up.

India is killing the Ganges, and Modi can do nothing about it

“A respectable showing here would energise the Congress. Already there are signs the BJP is now taking Rahul Gandhi more seriously, after having spent years dismissing him as a halfwit,” says Delhi-based talk show host, journalist and author Vir Sanghvi.

An anxious Modi has pulled out all the stops for this election. He has flooded Gujarat with pre-poll sops such as relief for farmers, pay rises for health and contract workers, and a raft of infrastructure projects. Having virtually stationed himself in the state for the past couple of months, he has held about 30 rallies in the past two weeks, deployed a third of his cabinet to campaign here, and even delayed the winter session of the Parliament for this election. Gujarat made Modi, now Gujarat can break him, and he isn’t taking any chances.

The Gujarat Assembly has 182 seats, of which the BJP won 116 and the Congress 60 in the last state election in 2012. This time, national party chief and Modi’s long-time Gujarat lieutenant Amit Shah has set a target of 150. The BJP’s best so far has been 127 seats in 2002, on the back of the religious polarisation after the Hindu-Muslim riots in Gujarat that killed more than 2,000 people.

Modi’s party stokes anti-Muslim violence in India, report says

Voter surveys in India are often a perilous exercise because of the unpredictability of the Indian voter. This time, while some surveys are predicting a tight race, others see a comfortable BJP win. But almost all surveys show the BJP’s vote share and winning margin narrowing.

A tally of opinion polls aggregating three surveys shows the BJP will get 105-106 seats, over the halfway mark of 92 needed to form government, and the Congress, 73-74.

“A narrow win will give BJP breathing space but will not allow them to gloat since they had claimed they would win 150 seats. But in politics, a win is a win and any victory will give the BJP a chance to ram home the point that they are India’s pre-eminent national party,” says Rajdeep Sardesai, TV host and author of 2014: The Election that Changed India.

MAIN CASTE

While the results in Gujarat will have far-reaching national repercussions, the source of Modi’s troubles in his power base is largely local – a troika of caste leaders who have allied with the Congress.

His biggest headache is Hardik Patel, a 24-year-old who is too young to run for election himself but has rallied the powerful Patel community with his movement demanding affirmative action for his caste. A jail term on sedition charges, a leaked sex video, nothing seems to stop Hardik Patel, who has been drawing huge crowds in his rallies while there are reports of thin attendance at Modi’s.

‘Reverse Bank of India’: How note ban has turned a revered institution into a joke

Most rural Patels have been reeling from India’s agrarian crisis while the younger members of the community in both cities and villages can’t find jobs. Small businesses, where Patels have traditionally invested, are also being squeezed out by bigger players. Estimated to account for about 12 per cent of Gujarat’s 63 million population, Patels have been the backbone of the BJP’s reign in the state, with the ability to swing the results in about 70 of the 182 seats. In Surat alone, Patels control nearly 70 per cent of the city’s diamond and textile business and directly influence results in five of its 12 assembly seats.

Jignesh Mevani, a 35-year-old lawyer who has emerged as a leader of the Dalit community of untouchables, is another thorn in the BJP’s side. Dalits make up 7 per cent of Gujarat’s population. Shooting to prominence after leading a Dalit movement last year, Mevani’s appeal in the community could make a major difference.

Another young caste leader who has successfully raised the issue of affirmative action and lack of opportunities is Alpesh Thakor, who has built up a sizeable organisation all by himself. Thakor is the biggest coup for Gandhi, who inducted him into the Congress in October.

The rise of these caste leaders threatens the BJP’s assiduous consolidation of a pan-Hindu constituency. Ever since the 2002 riots, Gujarat has been highly polarised along religious lines. This has meant caste differences have had to be subsumed in an overarching Hindu identity against the Muslim “other”. As a result, Gujarat’s 10 per cent Muslim population has been rendered politically irrelevant and is hardly visible in the current election.

Modi’s key aide blames poor planning for India’s currency crisis

By seeking rights and benefits for their communities, the caste leaders are exposing cracks in this Hindu unity facade. They are also negating a narrative that was central to Modi’s rise in national politics – the “Gujarat model”, or rapid industrialisation through business-friendly policies. Modi had convinced voters that he transformed Gujarat into an economic powerhouse and could do the same with India. Demand for assured government jobs by the likes of Patel and Thakor highlights the lack of economic opportunities in Gujarat today, raising questions about the very Gujarat success story that underpins Modi’s national appeal.

Economic prospects are likely to resonate particularly with the 1.2 million first-time voters in this election. These young voters, who have grown up seeing only the BJP in power and with little recollection of the 2002 riots, are less likely to be swayed by the BJP’s Hindu mobilisation and identify more with the youth leaders’ messages revolving around jobs and development.

The BJP’s vote share in the last state election in 2012 was 48 per cent while the Congress’s was 39. If the gap narrows, the seat tally could change radically. But few are ready to put money on a Congress win yet, given Modi’s bond with his home state and the demi-god-like status he enjoys here.

“As the favourite son of the state, Modi should be guaranteed a victory,” says Sanghvi.

Many who have been fuming at Modi may well eventually vote for the BJP anyway. The caste leaders may fail to deliver, and politics is not mathematics. But Sanghvi believes that even if the victory is a narrow one, it could work to the Congress’s advantage.

“If Rahul can show Modi is vulnerable even in his home state, it would mark a coming of age for him. The significance of Gujarat is not that the BJP may lose but that it may turn out to not be the invulnerable monolith it claims to be.”

And if popular discontent, caste coalition and silent Muslim rage do really coalesce to defeat Modi in the epicentre of his power, it will be a “political earthquake”, says Sardesai.

“It will open up a real opportunity for the opposition ahead of the 2019 general election by giving them momentum and self-belief. After all, if you can defeat the BJP in the prime minister’s fortress, why can’t you recapture India?” ■