Is it time to call code red on TikTok challenges and Gen Z’s obsession with popularity contests?

- TikTok challenges have encouraged trends such as Gen Z users believing they are ‘ageing like milk’ and changing up their image to fish for compliments

- The trend raises concerns about how social media has turned a supposedly ‘progressive’ generation into one obsessed with and hyper-focused on image

Before social media platforms became our preferred pools of toxicity, women had to wade through glossy magazines to feel bad about greying hair, stretch marks and their weight.

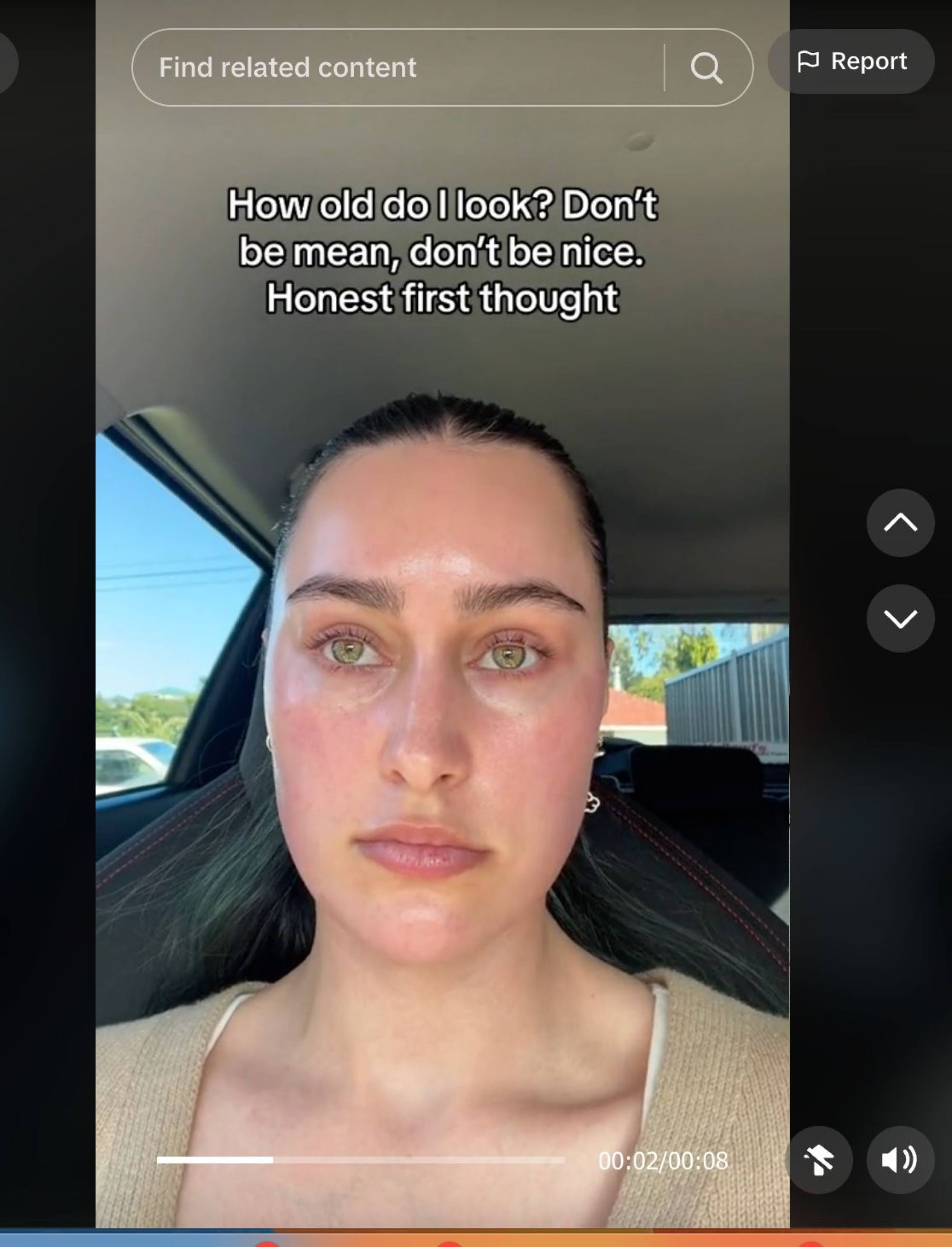

Now, there’s TikTok’s “challenge” culture, in particular, its recent trend of “How old do I look?”. It’s like watching impalas on National Geographic playing near the lions: you know it is just a matter of time before there is an attack.

Chinese tech company ByteDance’s wildly popular platform, which gets users to create and share short videos, is a country unto itself, with its own rules. Mostly harmless, its activities are pegged to a hashtag, theme or activity, such as lip-synching to a comedy skit or trying a dance routine. In this gamified ecosystem, users are rewarded for how much attention they generate.

Once you are through immigration, you can park your preferences on its “For You Page” (FYP). A bunch of ones and zeroes analyse your taste, so TikTok can serve you more of the same. As the algorithm prioritises engagement, videos that receive the highest number of likes and shares in the shortest time climb the FYP ranks, and are amplified to even more viewers.

TikTok challenges and trends are designed to feed this popularity contest. Viral videos generally are compelling or funny, pegged to specific themes, hashtags, songs or a set of instructions. Their creators are further incentivised with access to programmes, events and sponsorships.

The risk of insult is part of the thrill. Like first-time bungee jumpers, videos of those who answer the challenge usually start with some variation of “I might live to regret this but …”, then a plea to mitigate meanness: “please don’t be too harsh”.

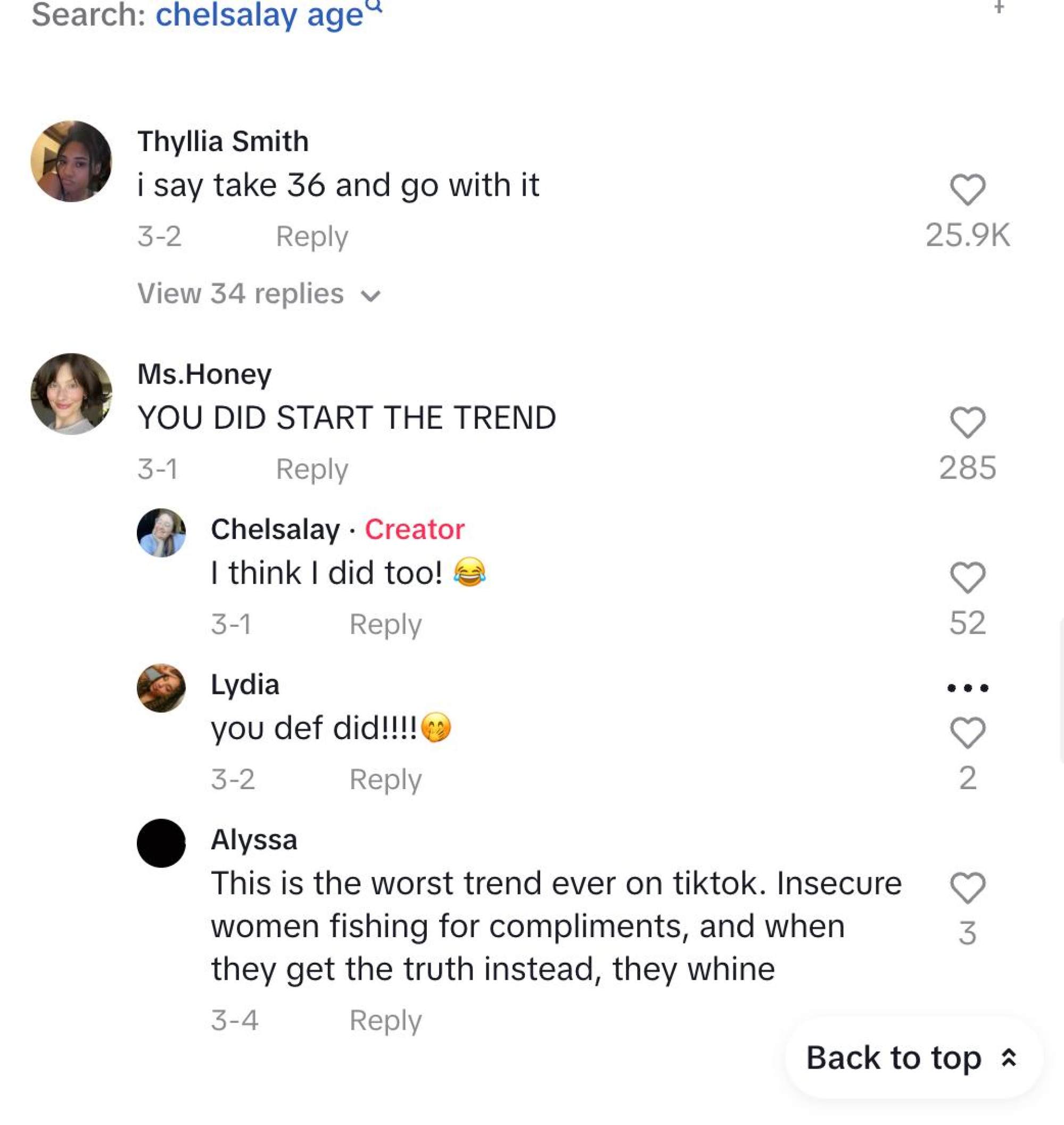

For attractive, dewy-skinned influencers, the fishing yields lots of compliments. @isabelle.lux, for example, uses the trend to market anti-ageing products, and get people to share their anti-ageing regimen too.

For the rest, attacks are savage. They run along the lines of “you look waaaay older than your age”, cruelly saying someone is in her fifties when she is clearly about 19, to body-shaming and bullying taunts about “Grandma vibes”, or flat-out hate speech, which to repeat would be to dignify.

But that’s the culture in TikTok-verse.

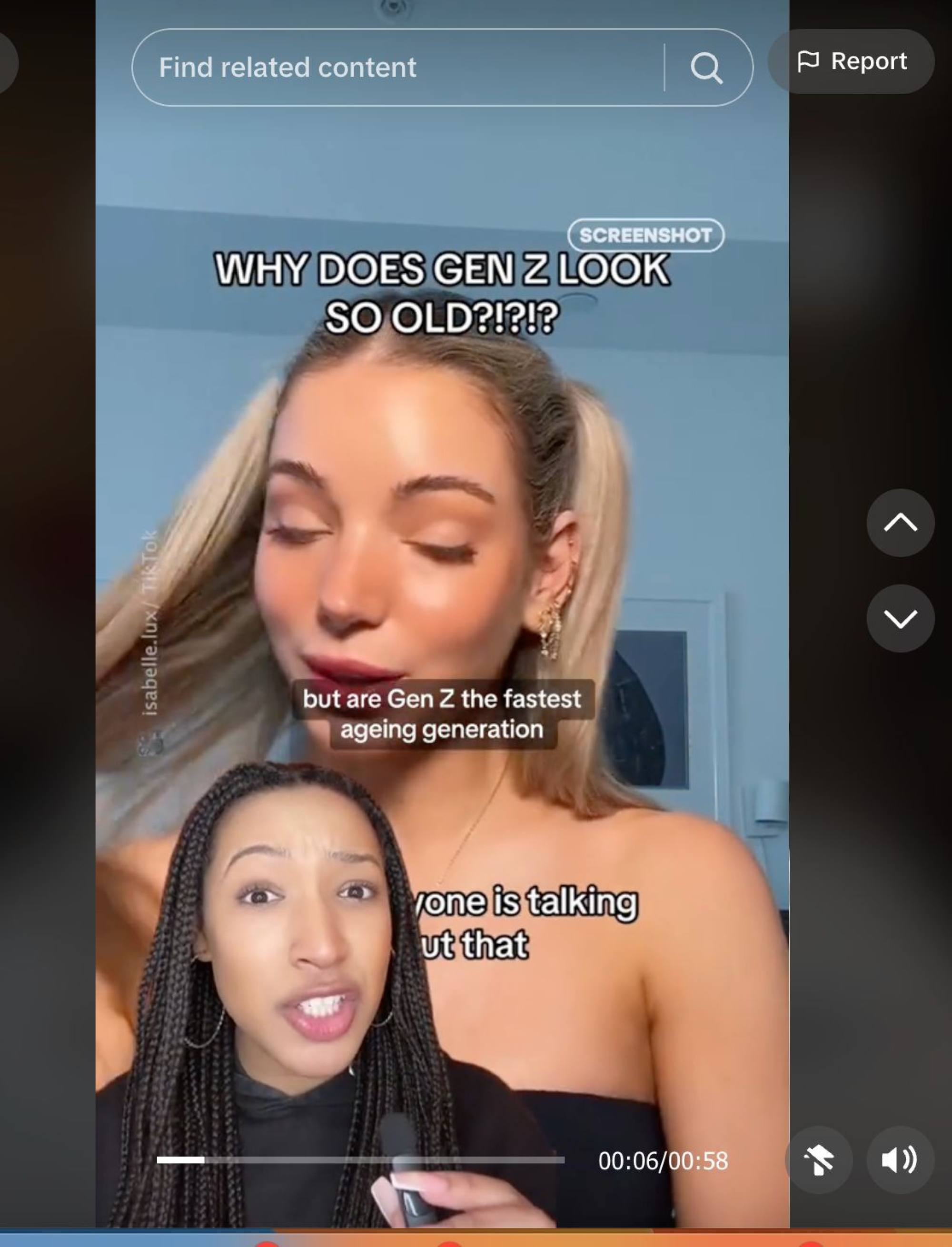

Still, it is users such as @TrinityShiroma who make you wonder if everyone got the brief. She opens with: “I’m prepared to get my feelings hurt by ‘how old do I look’ … because there’s this trend going around that Gen Z is ageing quicker, and I’m Gen Z.”

She is referring to women who are not even 25 years old, but who believe they are growing older more rapidly than millennials, or “ageing like milk”. Fearing they are already past their prime, they blame a host of causes – vaping, UV, stress, or the pressure of having to live up to the lives of others on social media; and fear they are already past their prime.

In real life, this anxiety is driving teens to seek plastic surgery, tweens to ask parents for anti-ageing serums, and little girls to worry about freckles.

How did this algorithm turn Gen Z on itself? When something is so powerful it drives users to behave entirely counter to their professed values of being progressive and inclusive – more “woke” than their predecessors – is it time to call code red?

True, social media has always had the potential to cause trouble. As early as 1997, Andrew Weinreich’s Six Degrees, a first-generation networking site which had users build profiles and share their friends list, sparked privacy concerns. By 2002, cyberbullies and sexual predators had emerged on Friendster and, later, MySpace. After its launch in 2004, trolls drove up teen suicide on Facebook, while gangs soon used it to recruit youngsters. In 2006, Twitter (now X) became a channel for hate.

TikTok at least also promotes voices of reason. Dr Yumiko Kadota, a specialist in plastic and reconstructive surgery in Sydney, Australia, pleaded on her account: “Can we please stop doing this ‘trend’? If you think you look younger than your age then you’re just fishing for compliments, and you look like a tool. If you look older than your age, then people are just going to be mean to you in the comments. So just stop doing it.”

Given how so many cannot tell the game from reality, content moderation should top the FYP of lawmakers anywhere, not just in the United States. Any media that rewards how well one person tears down another’s physical appearance is a cancer.

Although it is unrealistic to expect users, all so fond of clicks, likes and shares, to ditch their favourite channels in favour of mental health, watching a whole generation succumb to keeping up with hyper-processed images is frightening.

An entire Reddit thread obsesses over whether Barbie actress Margot Robbie looks 40 (she is 33). Socialite Kim Kardashian “freaked out” when her friend tried a filter that made her look her mother’s age. Six years ago, in 2018, Oscar winner Julia Roberts, then 50, admitted she had been hurt by Instagram flamers who shamed her for ageing badly, after her niece Emma Roberts posted a picture of the pair without make-up.

She had not asked anyone how old she looked. But if the textbook definition of “Pretty Woman” felt pain, what chance does anyone have?

Thirty years ago, women could at least leave magazines at the salon, regroup with friends to eat carbs without judgment, and discuss feminist Gloria Steinem’s purse in the latest Coach campaign. We might have, among other things, fantasised about gender equality – “men don’t worry about getting fat, jowly and bald, why should we?” – and toasted to platitudes such as “true beauty ages”.

Let’s not regress. Whatever the rules of engagement, toxic challenges should be managed as cigarettes: with warning labels, health advisories, taxes, and legal age for use.

Stop the insanity.

Serene Goh founded brand content company Brango Pte Ltd in 2019, and is the publisher of multimedia website WhatAreYouDoing.sg. She currently focuses on narratives of sustainability, heritage, and modern Asian relationships.