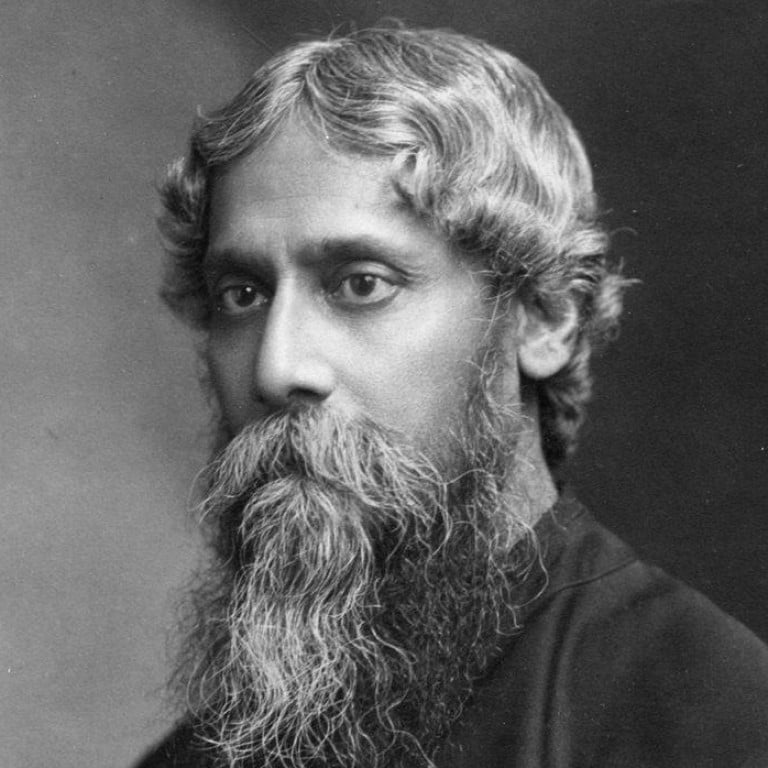

How celebrating the centenary of Rabindranath Tagore’s China trip can offer New Delhi and Beijing a chance to reset ties

- Marking the event could serve as a platform to revive cultural exchanges, reminding both that for most of human history, they have lived in peace

- Tagore centres for civilisational dialogue would help improve the image of China in India and vice versa, which is mostly shaped by Western narratives

One way of turning things around is to reflect on the times when the neighbours were engaged in the struggle to establish modern states and to take seriously a major thinker of that period, Rabindranath Tagore, who envisioned harmonious relations.

This April marks the 100th anniversary of Tagore’s visit to China and provides an opportunity to celebrate the occasion and study his vision.

His point of view was appreciated and he was effusively welcomed by several Chinese intellectuals, including Liang Qichao, who compared his visit with those of ancient travellers between India and China. In his introduction to Tagore, Liang spoke of how India and China had extensive contact in the past – most prominently through Buddhism – which was interrupted by colonial expansion. Western colonialism had not just hindered positive civilisational exchange; it had created the conditions for mutual suspicion and misunderstanding. Liang saw Tagore’s visit as reigniting the contact between two ancient civilisations in modern times.

Tagore also had a deep influence on modern Chinese literature. “I was so elated as if I had found a hidden orchid while strolling along a mountain path,” the author Bing Xin wrote in her moving tribute to discovering Tagore. Several Indians and Chinese travelled to each other’s countries after Tagore’s trip. India-China relations could be said to have reached a crescendo in 1954 with the signing of the Panchsheel agreement, which created a new paradigm for international relations. The subsequent sad break in ties needs no repetition.

However, the popularity of Tagore in China has only increased. He is widely known and is taught in Chinese school textbooks. In some ways, his ideas have more relevance at this time when both sides are re-examining the importance of their ancient heritage, and there are three key aspects of Tagore’s thought that deserve the attention of the world today.

The first is his critique of Western modernity. Tagore believed that in Western modernity, moral progress had not kept pace with scientific advances. He was a critic of Western nationalism, which he considered an abstract and limiting ideal driven by profit-making that had led to unnatural growth. He also questioned the excessive materialism of the West and believed that society should benefit from the gains of applied science, but that these must not overwhelm human relations.

Today, as China and India have both made immense material progress, much debate and discussion is focused on the shape that Chinese and Indian modernity is going to take. Both countries are seeking clarity on how their modern social organisation differs from that of the West, and its relationship to their ancient civilisational heritage. Scholars of China, for example, have noted the distinct state organisation in the country, referring to it as a civilisational state. Tagore emphasised that one must search for civilisational heritage in folk forms, in the ways and beings of ordinary people rather than in the culture of the elite.

The second is the doctrine of universal man. Tagore was immensely concerned with the place of the human being in society and directly confronted the complex problem of human experience in modern society. He believed that individuals would only find their self-expression in seeking to spiritually expand and unite with all of humanity. He thus sought an organic unity of humanity, which, in his view, would be guided by love. Individuals should strive to be “world-workers” who reject both rootless cosmopolitanism and narrow provincialism. Tagore further argued that Western nationalism was producing a limited sort of human being, and instead, there was a need to create what he called the complete moral man. He particularly emphasised the importance of education in developing human personality.

The third aspect is Asian unity. Tagore contended that it would be Asia that would show a new dawn to the world. Pan-Asia as an idea is often associated with Japanese thinkers, but the Nobel laureate was a critic of Japanese imperialism. He did not view Asia as a racial or geographical category but rather as a historical and political one. A synthesis of different cultures in Asia would develop in her “a confident sense of mental freedom, her own view of truth”. Otherwise, Tagore said Asia “will allow her priceless inheritance to crumble into dust, and trying to replace it clumsily with feeble imitations of the West make herself superfluous, cheap and ludicrous”.

As is evident to anyone who is paying attention, we are reaching the end of the era dominated by the West

What possibly could unite such a large land mass with such a huge variety of peoples and cultures? As the American scholar William Edward Burghardt Du Bois wrote “colored people vary vastly in physique, history and cultural experience. The one thing that unites them today in the world’s thought is their poverty, ignorance and disease, which renders them all, in different degrees, unresisting victims of modern capitalistic exploitation”. Pan-Asia was a theory shaped by the resistance to Western domination over the world. Du Bois, who was a founder of the Pan-African movement and an admirer of both the Indian freedom struggle and the Chinese revolution, expanded the Pan-Asia concept further to Pan Africa-Pan Asia.

Tagore declared that the time has come to “prepare the grand field for coordination of all the cultures of the world, where each will give to and take from the other; where each will have to be studied through the growth of its stages in history. This adjustment of knowledge through comparative study, this progress of intellectual cooperation, is to be the keynote of the coming age”. He felt that Asia must first seek to synthesise and understand its own heritage so it could properly assimilate the contribution from the rest of the world.

As is evident to anyone who is paying attention, we are reaching the end of the era dominated by the West. China and India will likely be the two largest economies in the world by 2050. The relationship between them and their cooperation will shape not only their own populations but the future of humanity itself. Unfortunately, there is currently a pitiful amount of contact between the two nations, who have maintained close communications with the West.

This is why it is important not only to commemorate the centenary of Tagore’s visit to China but also to take up his unfinished project of seeking a synthesis of Asian thought that requires Asian countries to know and understand each other. The image of China in India and vice versa is mostly shaped by Western narratives. Discussions tend to focus on realpolitik and narrow concerns. A small group of scholars certainly do have contact, but many of them are based in the West and their works have limited reach in broader society. Far wider association is needed. It would be apt to set up Tagore centres for cultural understanding and civilisational dialogue. Tagore’s own vision of the importance of his trip was summarised in his statement: “I shall consider myself fortunate if, through this visit, China comes nearer to India and India to China – for no political or commercial purpose, but for disinterested human love and for nothing else.”

The two societies must consider honouring the 100th year of Tagore’s visit to China, an event that would remind both that for most of human history, they have lived in peace with each other. A study of his thought will provide us with a modern vision for how they can continue this long-standing tradition.