Why Thai politics remains a rigged system with little chance of reforms

- Thailand’s Senate has an outsize role in who forms government because the bulk of the 250 senators are uniformed military or police personnel

- Several senators have stated they would not endorse Paethongtharn Shinawatra, former leader Thaksin’s daughter, even if she has the votes to form government

The behind-the-scenes manoeuvring is intensifying as party leaders contend with the reality of the senate’s outsize role, that makes the magic number for an opposition party to form government 376, not 251. Thai politics have never been so fluid.

Third, the election law prevents candidates from switching parties 30 days before the election.

Paethongtharn believes that an outright majority would make it difficult for the 250-member senate not to support her; otherwise the electorate may view the decision as theft. Disenfranchisement of voters in 2019 led to years of violent street protests, and the same could happen in 2023.

But her logic is flawed as key senators, including junta-appointed Wanchai Sornsiri, have already made it clear that they would never endorse the inexperienced 36-year old proxy for her father. Given that the bulk of the 250 senators are uniformed military or police personnel, they are part of the chain of command.

Pheu Thai, for its part, has also proposed two less triggering candidates – ones who aren’t the daughter of the former leader overthrown in a coup – party leader Cholnan Srikaew and property tycoon Srettha Thavisin, as it searches for potential coalition partners.

Second, the ultra-royalists are divided, for now.

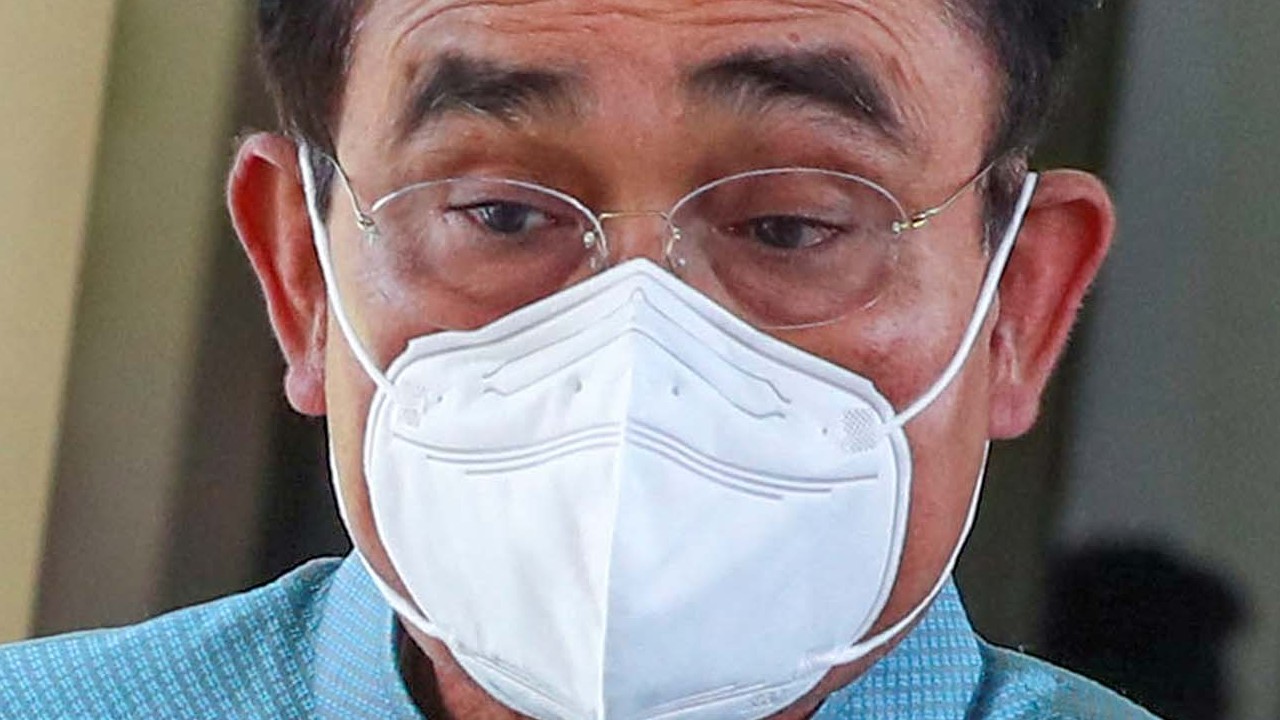

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha is weak. He survived a number of legal challenges, including one that gives him two more years in office. He also survived two no-confidence votes only through the thin parliamentary majority he enjoyed.

His poll numbers plunged as a result of his government’s poor economic performance during the pandemic, surging inequality, and continued legal repression and physical coercion against the opposition. Prayuth’s approval ratings sank to 14.5 per cent, dismal for an incumbent, though climbing again.

Prayuth joined the relatively new United Thai Nation Party (UTN), and brought some 30-40 Palang Pracharath Party (PPRP) members with him, including the head of the influential Sam Mitr faction.

Prawit Wongwusong is seen by the general public as both a dinosaur and the embodiment of all that is wrong with Thai politics

The PPRP is running retired general Prawit Wongwusong. But while trusted by elites, the 77-year old former coup leader is in poor health and seen by the general public as both a dinosaur and the embodiment of all that is wrong with Thai politics. The problem for the royalist camp is that PPRP has no other credible candidate who can compete at the national level.

While Prawit’s campaign has focused on providing numerous policy giveaways, it will not make up for the fact PPRP has been weakened by defections and poor performance. Its poll numbers plunged from 50 per cent in early 2020 to under 4 per cent in September 2022.

Former PPRP secretary general, Prawit protégé, and convicted drug smuggler, Thamanat Prompow, whom Prayuth ousted in 2022, is to return to the PPRP with 11 MPs. Prawit hopes Thamanant, a former deputy minister of agriculture, can develop some policies to win over the rural electorate and put a relatively younger face on the party.

UTN is likely to outperform PPRP. While Prayuth may only have two more years (unless the constitution its amended), he is a known quantity and a better campaigner with the power of incumbency.

Both parties will garner more than the 25 seat threshold for nominating a prime minister. But they will not split the vote: The military-royalist factions will coalesce around Prayuth. Indeed, not everyone believes the rift between Prayuth and Prawit is real, but rather a tactical move to earn more party list seats.

Third, Move Forward, under Pita Limjaroenrat, remains an important party especially among the urban middle class, despite facing a slew of lawsuits including a 100 million baht (US$2.9 million) defamation case currently before the courts. Move Forward has the best fundraising among the major parties, and is currently polling third or fourth. Its leaders have stood out in debates, but it has not broadened its support to the countryside.

Thai opposition files no-confidence motion against PM

While Move Forward and Pheu Thai were a solid block in 2019, that is less true today due to the former’s stance on monarchy reform. The PPRP, which is looking to make a deal with other parties including potentially former foes, sees the issue of the monarchy as too sensitive.

Fourth, the Bhum Jai Thai party has moved from a perennial coalition partner to the possible kingmaker. In 2019, BJT won 10.5 per cent of the popular vote, giving it 39 seats and 12 party list seats. But it has since gained more than 15 additional seats through defections, and recent polls suggest it could win upwards of 100 seats, making it the indispensable coalition partner. UTN and PPRP are unlikely to win the minimum 126 seats needed to form a government even with the support of the senate.

Any royalist-military coalition will also include the Democrat Party, led by commerce minister Jurin Laksanawisit. The Democrat Party is now largely a regional group but still likely to control around 40 seats.

BJT’s leader Anutin Charnvirakul has some crossover appeal, despite his low-level national support at 5 per cent in a late-2022 poll. A former Pheu Thai member, he is serving in the PPRP government as health minister. Prayuth could hold the reins with a promise of a handover in 2025 when his term limit is reached.

In essence, it remains a rigged system, with a dangerous mix of a very unpopular leader, from an unpopular party, who is likely to hold onto power. Yet, there is insufficient pressure for the royalist-military establishment to make any meaningful political reforms.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington DC, where he focuses on Southeast Asian politics and security issues.