Do China’s leaders care about what foreigners say about the country?

- Yes and no. China still craves international endorsement, but believes it is no longer the humble apprentice who used to learn from the masters in the West

- Rather than try to change the English-language international media’s echo chamber, Chinese officials are busy constructing an echo chamber of their own

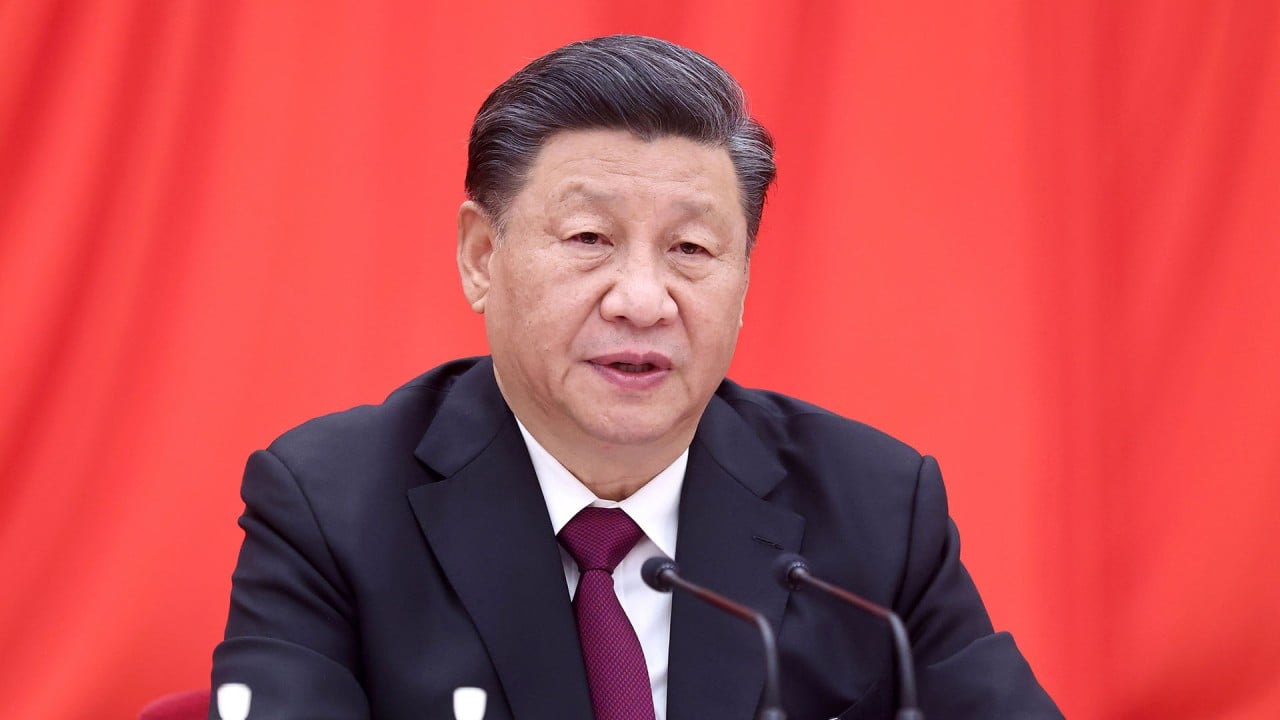

Do China’s leaders still care what foreigners say about the country? Do they get it that Beijing’s aggressive approach to its changing international environment has lost it friends and stoked disapproval in many parts of the world?

But that is not how people outside the country feel. China’s wolf warrior diplomats respond aggressively to foreign government officials or individuals who challenge Beijing’s narratives on sensitive issues; the state media pushes back strongly against critical reports in the overseas media and labels them as anti-China; the nationalistic online warriors within China go after anyone who tries to present views different from the official line as unpatriotic or appeasing to the West.

How China’s leaders stay in touch with reality

Put simply, China gives an impression that it brooks no criticism from anyone, constructive or otherwise.

There are a myriad of reasons behind China’s momentous shift in its approach and rhetoric to its foreign relationships. One important one is that China believes it is no longer the humble apprentice who used to learn from the masters in the West.

In the early years of China’s reform and opening up, Deng Xiaoping reportedly said that China should be on good terms with the US simply because those countries which followed the US had all developed well.

At the first high-level meeting between Beijing and the Biden administration in Alaska in March, China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi publicly rebuked the US for not being qualified to “speak from a position of strength”.

Xi and other senior officials have used multiple occasions to stress that Beijing no longer accepts sanctimonious preaching from the so-called masters (read: the US and its Western allies) who feel they have the right to lecture China.

As China plays a long game, Xi has publicly said that time and momentum are on China’s side, indicating an intention to hunker down for a protracted struggle with a declining but still potent US. Meanwhile, other senior officials have openly talked up a supposedly inevitable trend of East rising and the West declining.

Why rising ultra-left nationalism endangers China’s development

Their optimism is apparently based on the belief that so long as China focuses on its own priorities to ensure its GDP surpasses that of the US to become the world’s largest economy by the end of the decade, the rest of the world will see China differently as its own position of strength improves.

Instead, Chinese officials are busy constructing an echo chamber of their own. This month, China held its annual Understanding China Conference in Guangzhou, a premier forum aimed at helping the international community to better understand China’s domestic and international strategies. But it merely succeeded in preaching to the choir as the list of foreign attendees is carefully vetted and overseas journalists – including those from the South China Morning Post – were denied press credentials to cover the event.

To be sure, China has not quit its efforts to sway international opinions, particularly in developing countries, as it positions itself as the champion of multilateralism and free trade. For instance, China has sent billions of vaccine doses to the African and Arab countries – where Chinese media have beefed up their operations – and has promised to encourage more exports from those countries.

Wang Xiangwei is a former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper