After Covid-19, Malaysia must offer migrant workers a fairer deal

- As the country ponders its post-coronavirus future, it has a small window to achieve a more humane, progressive and efficient system

- The emphasis should be on the skills and productivity of Malaysian workers, rather than prohibitions on non-citizens

Among Malaysia’s “post-coronavirus” futures, few present as clear a reset window as its migrant labour regime.

Talk of change after the pandemic can be premature and presumptuous. So much remains enveloped in uncertainty and widespread “wait-and-see” postures. Not to mention, Covid-19 is fiercely surging, not subsiding.

However, in the migrant worker domain, Malaysia’s commitments and plans are laid out. The country has a window of opportunity to deliver already-made promises – precisely because the pandemic continues to rage.

Hundreds of thousands of migrant workers have returned home – or having lost their job which automatically invalidates their work permits, now live in the shadows as undocumented residents.

Total foreign worker permits plummeted from 2 million to 1.4 million in 2020. The last time Malaysia touched that level was in 2004, in the middle of a continuous, steep climb from 800,000 in 2000 to 2 million in 2008.

The Global Financial Crisis marked the start of a downtrend in permits and expansion of undocumented labour, until a massive regularisation and registration exercise ballooned the number of permits from 1.6 million in 2012 to 2.2 million in 2013. The figure hovered at 1.8 to 2 million in 2016 to 2019.

The current dearth of migrant workers, who perform manual jobs on plantations and construction sites, and long hours of routine tasks in manufacturing, is hitting many industries hard.

In a sense, this outcome aligns with the national objective of reducing reliance on imported labour, although the current worker shortage has also emerged abruptly and out of circumstances beyond employers’ control.

Malaysia has frozen new hires from abroad since the middle of last year. The ongoing rise in Covid-19 infections in major source countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal and Indonesia means that mass re-entry will not happen any time soon.

Pressures are mounting, especially from plantation companies, for relief from the worker shortage. A “labour recalibration” programme allowing the employment of undocumented workers, and extension of plantation workers’ permits for a year, will not be enough.

However, beyond the question of selective unfreezing of foreign worker recruitment, an opportunity presents itself to make good on the more humane, progressive and efficient migrant worker system that Malaysia has repeatedly committed to.

For one, Malaysia can further extend positive moves made in recent years.

It formally eliminated the domestic labour outsourcing industry to curtail the power of middlemen who are often responsible for worker abuse and exploitation. Malaysia also extended more social protection to migrant workers, and paid more heed to forced labour conditions.

But the country is far from a breakthrough. Outsourcing persists under different forms, most migrant workers have not been registered for social security, and forced labour exposés recur.

Malaysian authorities should decisively streamline the management of migrant worker inflows through formal channels, protecting workers and pressing employers to meet their obligations. For example, it should continue pressing employers to comply with legislated worker housing standards.

Second, it should look at how to boost the skills and productivity of Malaysian workers and see how good jobs can be created for them in the manufacturing sector. Such operations are urban-based, where youth predominantly reside, and enjoy greater scope for technological progress.

After all, with the government adopting a sectoral approach to migrant worker dependency, the labour import freeze that currently applies across the board will continue for manufacturing firms even after the restriction is relaxed for other sectors.

01:48

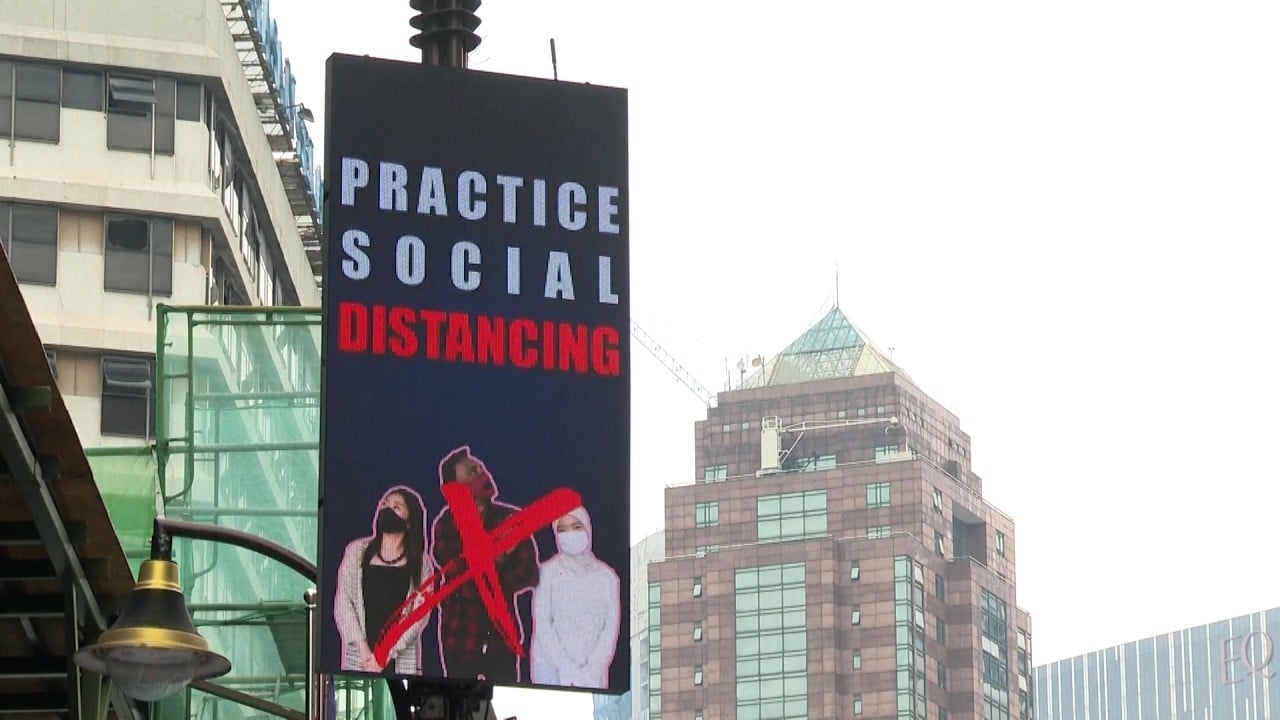

Malaysia tightens restrictions as total Covid-19 cases pass 500,000

In the plantation, agriculture and construction sectors, the prospects of replacing foreign with local workers are dimmer, and the prevalence of undocumented workers higher. Past trends of economic recession displacing the formally employed into the informal economy is not only likely to repeat this time, but might be more severe since borders are tightly controlled.

It will be a terrible waste if, in the years ahead, Malaysia drifts towards a repeat of previous cycles of undocumented worker build-up, followed by a haphazard mix of crackdowns and deportations on the one hand, and amnesty and regularisations on the other.

The current rigid system, which locks each worker permit to one employer, exacerbates exploitation because the employer’s ability to rescind the visa gives them excessive clout or induces workers who lose or leave jobs to take on informal jobs.

If workers can switch employers without any hassle or penalty during the current crisis situation, why not allow for this to continue when some form of normalcy returns to the economy?

The placement of migrant labour decision-making power under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MOHA), instead of the arguably rightful custodian, the Ministry of Human Resources, cannot be ignored as a major contributing factor.

The establishment of a massive labour outsourcing industry happened under MOHA’s watch. The recent case of a syndicate making counterfeit passes – allegedly involving immigration officers – reflects the propensity for fraud and corruption, and continual vested interest in profiting from commodified migrant workers.

The need for jurisdictional transfer to the Ministry of Human Resources preceded the pandemic, and will persist beyond.

Politics clearly militate against reform. But as long as the window remains open, any progress that can slip through should be welcome.

Hwok-Aun Lee is Senior Fellow and Co-coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Programme at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.