Muhyiddin’s grand plan for Malaysia’s development lacks clear focus when it comes to Bumiputra

- The Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 remains high on placebo promises but short on policy specifics. It is seemingly oblivious to its overlaps, misalignments and incoherence

- It fixates on reducing wealth inequality and focuses too narrowly on corruption and leakages as the primary problems with the Bumiputra development agenda

The real surprise was that Muhyiddin’s recent discussion reflected none of the introspection that was supposed to have occurred in the preceding 12 months.

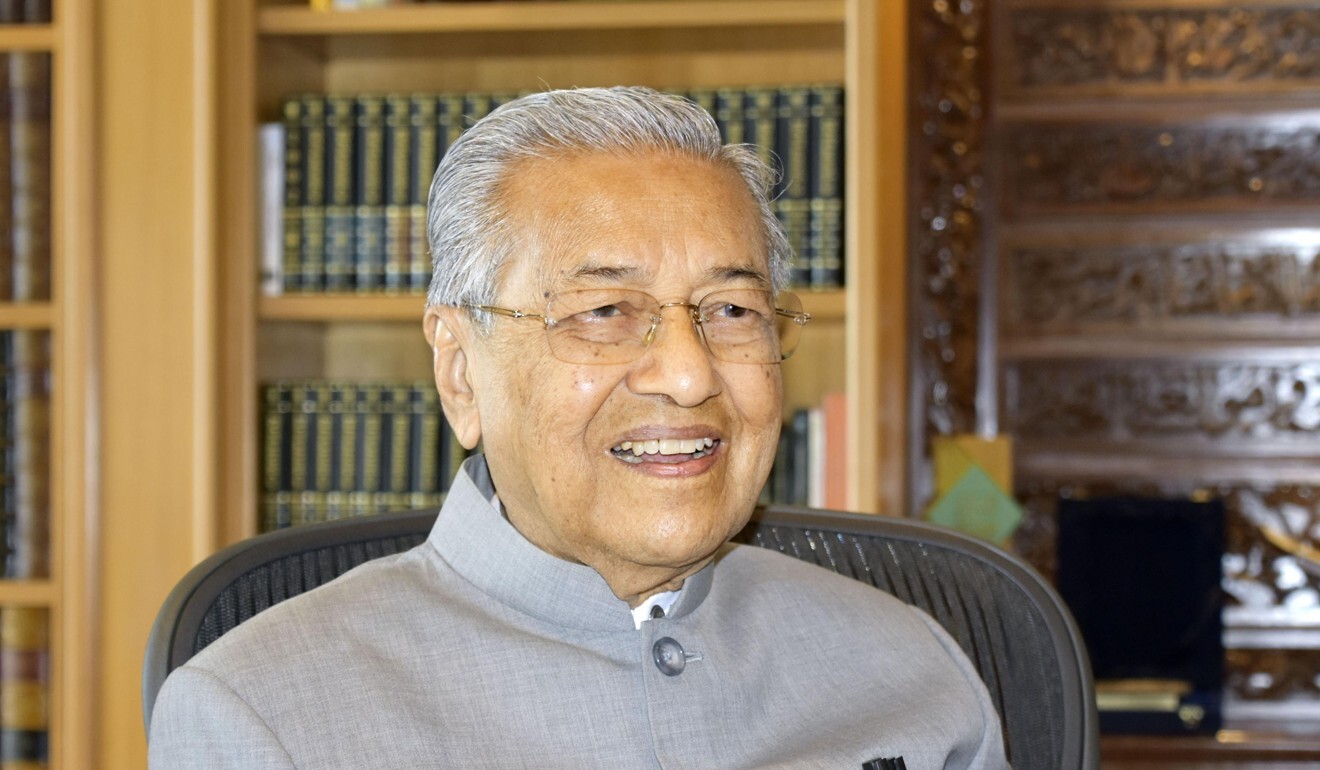

Can Mahathir’s government get Malaysians to believe in shared prosperity – regardless of race?

SPV2030 remains high on placebo promises but short on policy specifics. It is seemingly oblivious to its overlaps, misalignments and incoherence. Its new plans are primarily operational: the creation of a Shared Prosperity Action Council (MTKB) chaired by the prime minister and a Shared Prosperity Delivery Unit (Sepadu) to monitor implementation. It is unclear why another government agency is needed, especially when the Economic Planning Unit remains Malaysia’s official guardian of development.

To its credit, the plan addresses the potential downsides of monopoly power and low wage share in national income. But its “progressive” aims are opaque and amorphous, suggesting priority will be given to income inequality between classes and poverty alleviation.

By contrast, SPV2030’s second objective is notably specific. It targets wealth and income inequality based on “income group, ethnicity, region and supply chain” – so that “no one is left behind”. How these objectives are distinct from the first objective’s “progressive” economic restructuring remains obscure.

Muhyiddin also identified wealth inequality as a source of racial tension, presumably because Malays regard non-Malay wealth with suspicion. This is a popular but unproven assertion.

Indeed, recent experience suggests Malaysians generally view runaway wealth accumulation without an ethnic lens. After the 2018 elections, Malaysia’s government slashed the stratospheric salaries of some government-linked CEOs – an all-Malay line-up – seemingly to popular approval. While this technically affects pay packages, not wealth stocks, it is still worth noting that there was no revolt against a segment of Malay wealth being curtailed. Will Muhyiddin now call for CEO packages at government-linked companies (GLC) to be reinstated so inter-ethnic wealth gaps can be narrowed?

Such wealth is far removed from the average Malaysian, and there is little evidence of widespread enmity toward the wealthy within another ethnic group. Malaysia’s ethnic tensions may stem from socioeconomic conditions but revolve around access to opportunity.

Muhyiddin’s government and Malaysia’s fragile status quo cannot last

Tensions derive more from Malay anxiety that the privileges they enjoy might be eroded while the community has yet to secure economic footholds, and non-Malay grievance toward unequal opportunities arising from the same system of pro-Malay preferential treatment.

Vast sections of the Bumiputra receive special access to residential schools, pre-university and university programmes, technical colleges, microfinance, public sector and GLC procurement. Non-Bumiputra are not totally excluded but unequal access, especially to public higher education, remains contentious.

Preferential programmes for Bumiputra are deeply embedded but their ultimate goal, discreetly acknowledged in Malaysia’s recent development documents, is for beneficiaries to graduate and exit, giving way to more open access and equitable distribution in line with long-term aspirations.

Malaysia is not there yet. It is therefore misguided to focus on wealth instead of issues of capability and participation – the competitiveness of graduates, the concentration of Bumiputra business at the micro-scale and the dearth of medium-scale enterprises.

As more Malaysians learn Mandarin, Chinese schools call for recognition

The SPV2030’s fixation on reducing wealth inequality and its narrow focus on corruption and leakages as the primary problems with the Bumiputra development agenda fails to grasp how the system operates and where it falls short. The key to graduating out of the system and fostering more inclusion and competition, while also allaying Malay economic anxiety and unease about preferential treatment, is to develop Bumiputra capability, competitiveness and self-sufficiency, especially through higher education, entrepreneurial development and SME support.

“Nobody will be left behind. Prosperity is colourblind,” Muhyiddin said at the end of his speech last month. “It must not discriminate against anyone. All of you, regardless whether you are a Malay, Chinese, Indian, Sikh, Iban, Kadazan, Dusun, Murut, Bidayuh, Bajau Melanau, Orang Asal – all of you – have the right to be prosperous and successful in this country.”

Those words may be music to many ears but the substance rings hollow. Not because it is insincere, but because it is incoherent.

Hwok-Aun Lee is Senior Fellow and Co-coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Programme at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, and author of Affirmative Action in Malaysia and South Africa: Preference for Parity.