Golden era with China, or special relationship with Trump? Brexit Boris must choose for Britain

- Managing relations with the warring world powers will be a delicate balancing act for new British prime minister, Boris Johnson

- He has expressed interest in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, but will the US-Britain ‘special relationship’ tip the scales in America’s favour?

According to Brexit supporters, Britain’s decision to leave the European Union is not about turning its back on the world. Rather, it is about staking out a new position in the global economy as a sovereign state that can make deals with like-minded partners without the constraints of being an EU member.

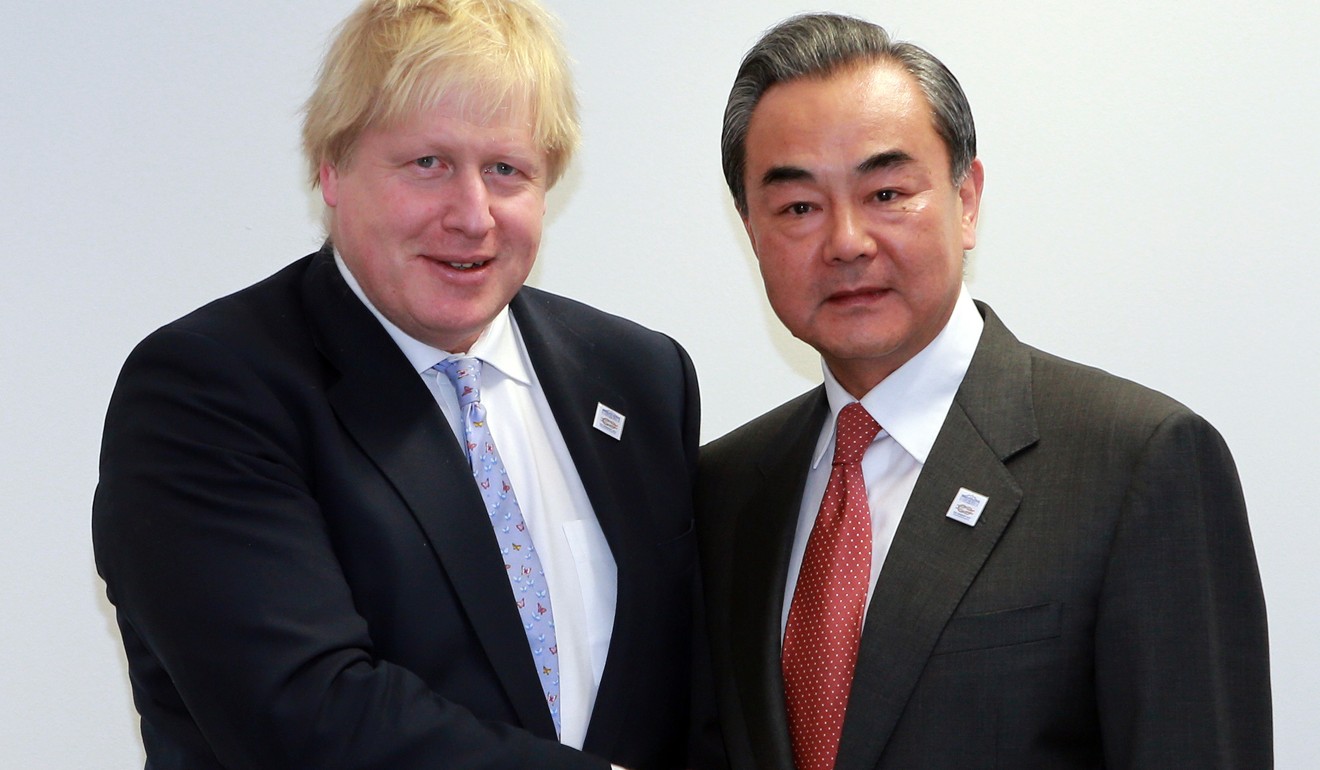

Britain’s new prime minister, Boris Johnson, is apparently seeking what some British diplomats have called a “special relationship” with both powers, as Britain is hungry for new partners and markets to offset any losses in its relationship with the 27 nations that will remain in the EU.

Brexit Britain is missing an Asia policy

In an interview with a Hong Kong broadcaster a day before he succeeded Theresa May as prime minister, Johnson said his government would be very “pro-China” and that the British were “enthusiastic” about the China-centred trading network that Beijing was building. Johnson, who campaigned for Brexit ahead of the referendum in 2016, also vowed to keep Britain “the most open economy in Europe” for Chinese investment.

He has pledged to extricate Britain from the EU by October 31 “come what may”, but a no-deal Brexit would likely precipitate a trade war of sorts, which could be catastrophic for the British economy if Johnson can’t negotiate favourable parallel trade deals with the US and China in time. The risk of a recession might drive him to rush into their embrace immediately. Britain already receives more Chinese foreign direct investment than any other EU country and is one of Beijing’s top three trade partners in Europe.

However, the new boss at 10 Downing Street has to deal with a host of challenges facing London’s relations with both powers amid an intensifying US-China confrontation. In some cases, the British will have to choose sides, as an accord with one may mean discord with the other.

How Brexit Britain can gain from China’s Belt and Road

At the time, London’s move angered Washington and the new British leader’s comments on Beijing’s belt and road plan may suggest another similar challenge to Britain-US relations. Johnson’s predecessor Theresa May had refused to sign a memorandum of understanding that would have lent the Chinese project official endorsement from Britain.

So far, Italy is the only G7 nation to have signed up the belt and road project, irritating the Trump administration in the process. If Britain were to also hop on board, it would hurt its relations with Washington – as it would suggest a preference for doing business with Beijing, so long as its serves Britain’s national interest.

Britain will also have its hopes pinned on a free-trade agreement with China post-Brexit, but this could again cause friction with the Trump administration, which has warned its allies against making such deals as they could be in breach of agreements with the US.

In a trade document outlining the US’s priorities in March, Washington indicated that London may have to pick between it and Beijing. The White House has signalled that any trade pact with Britain would effectively bar it from signing one with China. It warned of “appropriate action” if the country negotiates a trade deal with a “non-market country” – an obvious reference to the communist state.

Why Brexit strengthens Beijing’s hand in the South China Sea

In sharp contrast, Britain’s “special relationship” with America – a term coined by the former British prime minister Winston Churchill in 1946 – is rooted deep in history, with the seeds of a common language, culture, lifestyle and religion having been sown hundreds of years ago during the time of the Thirteen Colonies.

US-China trade war and Brexit casting shadow over Hong Kong economy

In the end, the US-UK relationship is destined to be more “special” than the UK-China one. Whenever London is forced to choose, it will side with its first love. ■

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on the topic since the early 1990s