US-China trade talks: has Beijing been playing an ancient game?

- For centuries, Westerners with a superiority complex have entered negotiations with the Chinese convinced they were winning, only to miss a greater irony

Even the most casual student of the history of China’s relations with the West will know something about the famous failed embassy of George Macartney to the Qianlong Emperor in 1793. Reading the king of England’s haughty letter to the Chinese emperor alongside the emperor’s equally haughty reply remains an excellent object lesson in nonconversation. George III asked for the right for English merchants to live and work in China and to have access to Chinese markets. He sent presents. Qianlong replied with even more magnificent gifts but refused the king’s requests point by point. China needed nothing from the outside, he wrote, and certainly nothing from the Western Ocean people who had at last come to pay tribute to the Middle Kingdom and the centre of the world.

The Chinese were white – until white men called them yellow

Much has been written about the immense distance between these two positions, and the exchange has served as a symbol of a wide variety of interpretations about relations between the West and China both past and present. Indeed, deciphering the exchange takes on a particular pertinence given the ongoing trade negotiations between Washington and Beijing.

What few readers know, however, is that this pattern of Western request and Chinese denial stretches back to the very earliest contact between the two sides. Before 1842 and without exception, these encounters were all in Chinese control. Western visitors got almost nothing they asked for and were not allowed to remain; they were told that the only way they could interact with China was by obeying its laws of tribute, even if these rules were largely symbolic.

Tribute regulations were a means of restraint, invoked or relaxed as necessary but nonetheless functional. But in a sense the West became part of the Chinese world much more than the other way around; despite the Europeans’ best efforts, in other words, these were not embassies to China, they were tribute missions.

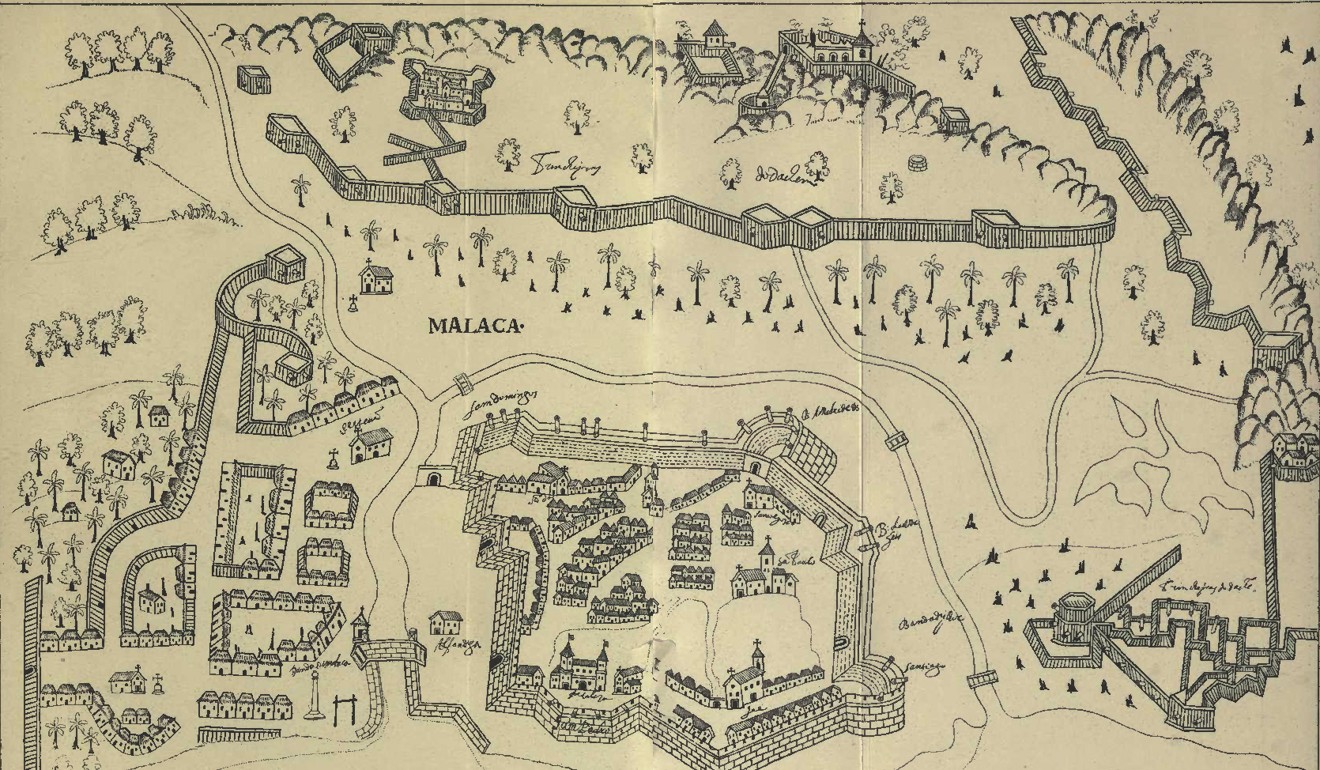

In this sense all the embassies were failures, at least from the Westerners’ point of view, and even those few requests that were granted were conceded on a limited basis and only in terms dictated by the Chinese. The first official embassy, sent by Portugal in 1515, arrived in Canton via the recently established Portuguese stronghold at Malacca.

The entourage hoped to set up a trading post similar to the many others in their burgeoning overseas empire. They claimed to be on a mission of friendship from the Portuguese king, but it soon began to dawn on officials in Guangzhou that the newcomers were really attempting to monopolise the already existing trade and to set up long-term fortifications by force of arms.

In a disastrous development for the Portuguese and for European relations generally, the ambassador and his entourage were thrown into jail, where they died one by one over the course of many years.

Why Trump’s trade war is a blessing in disguise for Chinese leaders

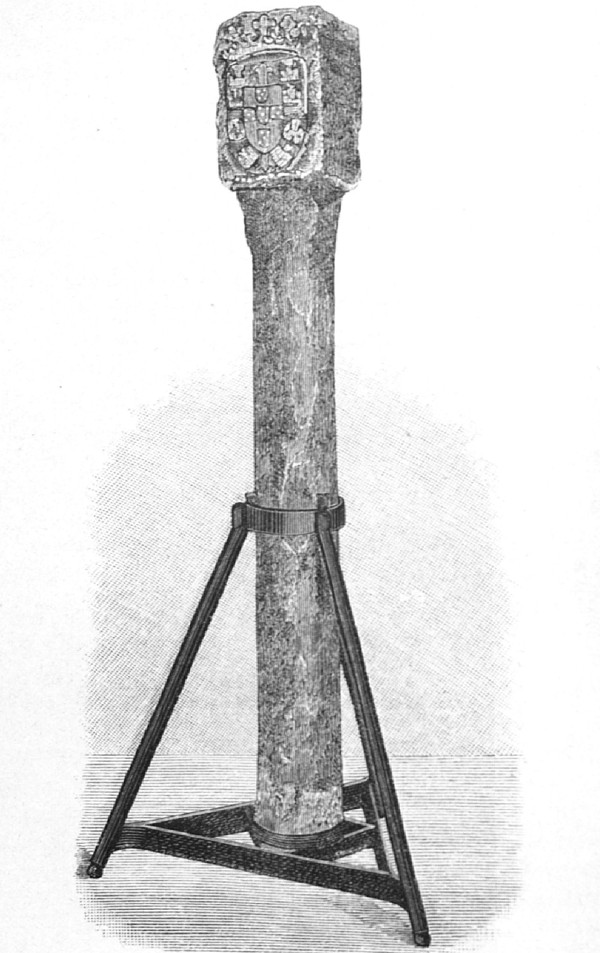

Chinese sources accused the newcomers of many illegal activities, including “setting up stones”, which almost certainly refers to the Portuguese custom of installing stone pillars as symbols of their expanding empire, which at its height encompassed seaports from West Africa to Japan. Evidently, one had been erected at Tunmen, now part of Hong Kong’s New Territories, to show that China had also been “discovered” by the Portuguese crown. Yet this was a vision of empire that differed markedly from the Chinese understanding of international relations, since in principle China did not seek to absorb other lands or to impose its form of government or religion on foreign peoples.

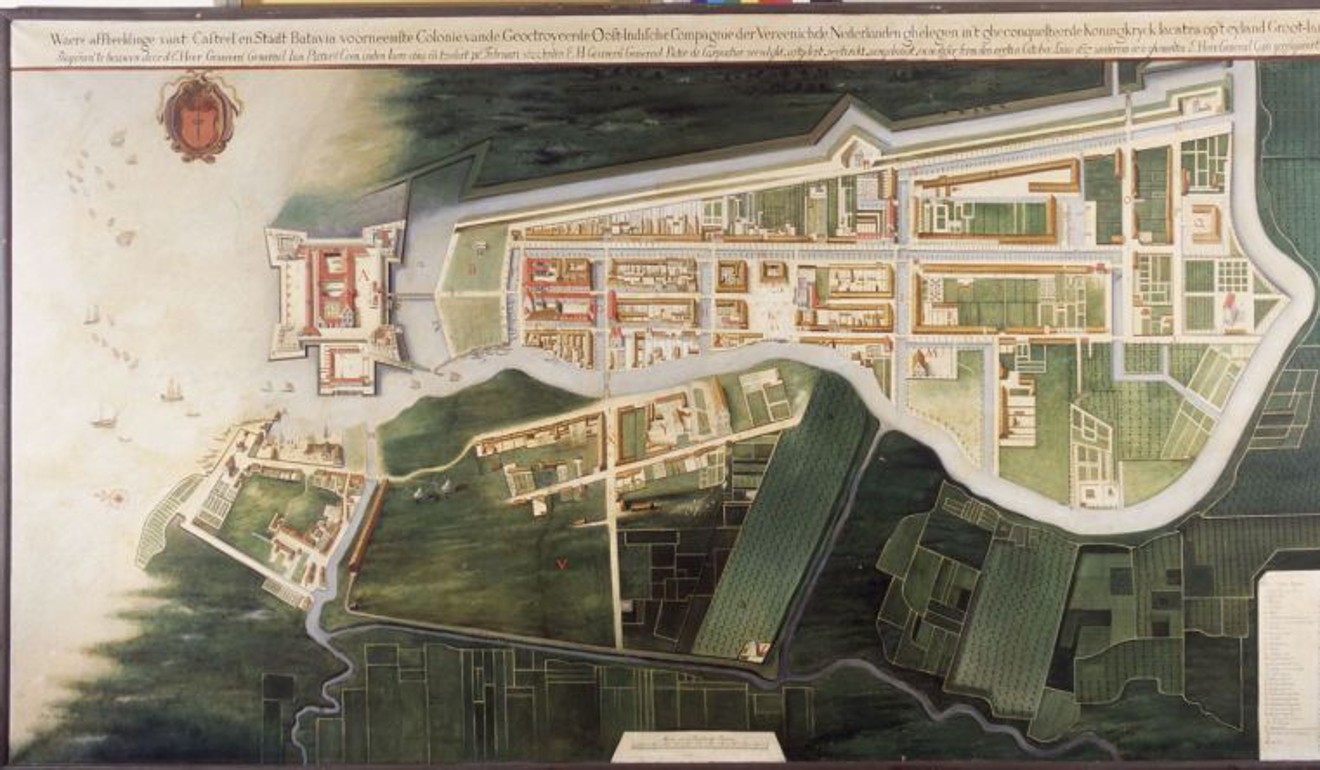

The next embassy was from Holland in 1655, originating in its own regional base of operations at Batavia, present-day Jakarta. Not claiming any interest in territorial expansion at first (they had already occupied southern Taiwan since the 1620s), the Dutch requested what they called a “free trade” agreement, by which they meant a mutual exchange between nation-states unfettered by private or governmental controls.

But in China there was no such thing as free trade, and even if tribute-bearing status was granted, it carried its own set of rules at odds with the Dutch demands: all tribute bearers were assigned ports of entry, they were given a maximum number of ships and men and told how long they would be allowed to remain, and they were informed how many years should elapse before the next tribute mission could be undertaken.

The Dutch envoys, who were in reality merchants in the employ of the Dutch East India company, had to overcome the fact that their insistence on mutual profit seemed to have little effect on Chinese officials, whose tradition taught them that trade was a low priority and that merchants should be placed at the very bottom of the social scale. The Dutch hoped for unrestricted yearly trade, but instead were sent away with an imperial edict telling them that they might pay tribute to the emperor but would have to wait another eight years to return.

Other embassies fared little better. There was, however, one major exception: Russia, which received many favours that were consistently denied to other European nations. In 1689 a treaty was signed that guaranteed “mutual commerce”, and for the next decade Russian caravans came to Beijing every year (and about every two years after that).

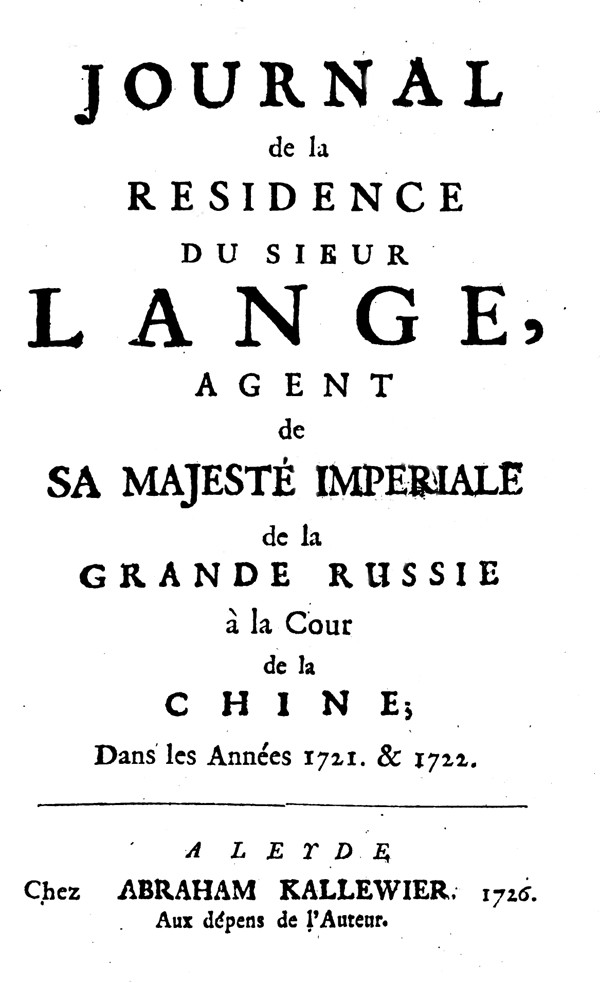

Secondly, unlike the small number of Roman Catholic missionaries who were allowed to live in China, another treaty in 1727 gave Russia the right to establish a permanent Russian Orthodox mission in the capital. Most remarkably of all, in 1721 a visiting Russian ambassador was granted permission to install a representative in Beijing who would oversee all Russian commerce and, when problems arose, speak for the Russian empire and its various policies.

How do we explain this? The simple reason was that Russia was not seen as a Western Ocean country. The Russians were a “border tribe”, and their affairs were administered by an office that dealt with a complex set of nomadic peoples to the north and west beyond the Great Wall, an area fraught with dangers and numerous invasions. China thus came up with a policy in which allowances could be made in exchange for Russia’s non-interference in central Asia – crucial for maintaining a balance of power.

Frequent trade was one such concession. Another was the right to install a Russian “consul” in Beijing, although it lasted only about two years. Western-style diplomacy might be allowed to function at certain times and under certain circumstances, but this did not mean China had altered its traditional attitude towards foreigners or that the West’s point of view had somehow managed to win out. On the contrary, Russia’s hopes for commercial profit, religious freedom, and diplomatic recognition, like those of all other Western nations, remained largely unfulfilled.

Trump’s China-bashing more class war than trade war: Thomas Piketty

The ambassadors did not hide their disappointment and frustration, but a much more interesting undercurrent in their accounts is the way in which European pretences were constantly being deflated by Chinese interlocutors. Such irony was typically lost on Western narrators, who considered themselves superior to anything they encountered in the Middle Kingdom. For both sides, perhaps, the real motives of the other remained somewhat inscrutable, but when two versions of empire, trade, and diplomacy collided, the Chinese side nearly always seemed to emerge victorious, and the West’s desires, whether they were ever understood or not, could be rendered completely superfluous.

But at the conclusion of the First Opium War in 1842, many things changed. China became a colonial contact zone. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain and a number of ‘treaty ports’ were forcibly opened, where foreigners could reside year-round and trade with anyone they wished. For the first time in its history, China had to bow to the dictates of Western desires. ■

Michael Keevak is Professor of Foreign Languages at National Taiwan University and author of ‘Embassies to China: Diplomacy and Cultural Encounters Before the Opium Wars’