Mahathir’s pushback against Chinese deals shows belt and road plan needs review

Xi Jinping’s signature strategy has shown significant progress, but Malaysia’s decision to shelve two China-financed mega projects is the latest sign improvements are required

In October that year, while visiting Indonesia, he followed up by suggesting a “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, tracing the old trading routes that took Chinese merchants to Southeast Asia, Arabian countries and all the way to eastern Africa.

Where does Imran Khan’s government stand on China’s belt and road?

The overseas media have invariably described the initiative as the Chinese version of the Marshall Plan, a United States government initiative to rebuild Europe after the second world war. However, Chinese officials have shied away from endorsing the comparison, because the US plan had the strong geopolitical intent of supporting its European allies and isolating what was then the Soviet Union.

Still, many have seen Xi’s signature campaign as China’s boldest attempt yet to project the country’s political, economic and cultural influences at a time of profound changes across the world, particularly in the US and Europe.

From last month, state media have ramped up propaganda to mark the fifth anniversary of the grand plan and catalogue achievements ranging from China-built railways in Ethiopia to the China-owned Greek port of Piraeus.

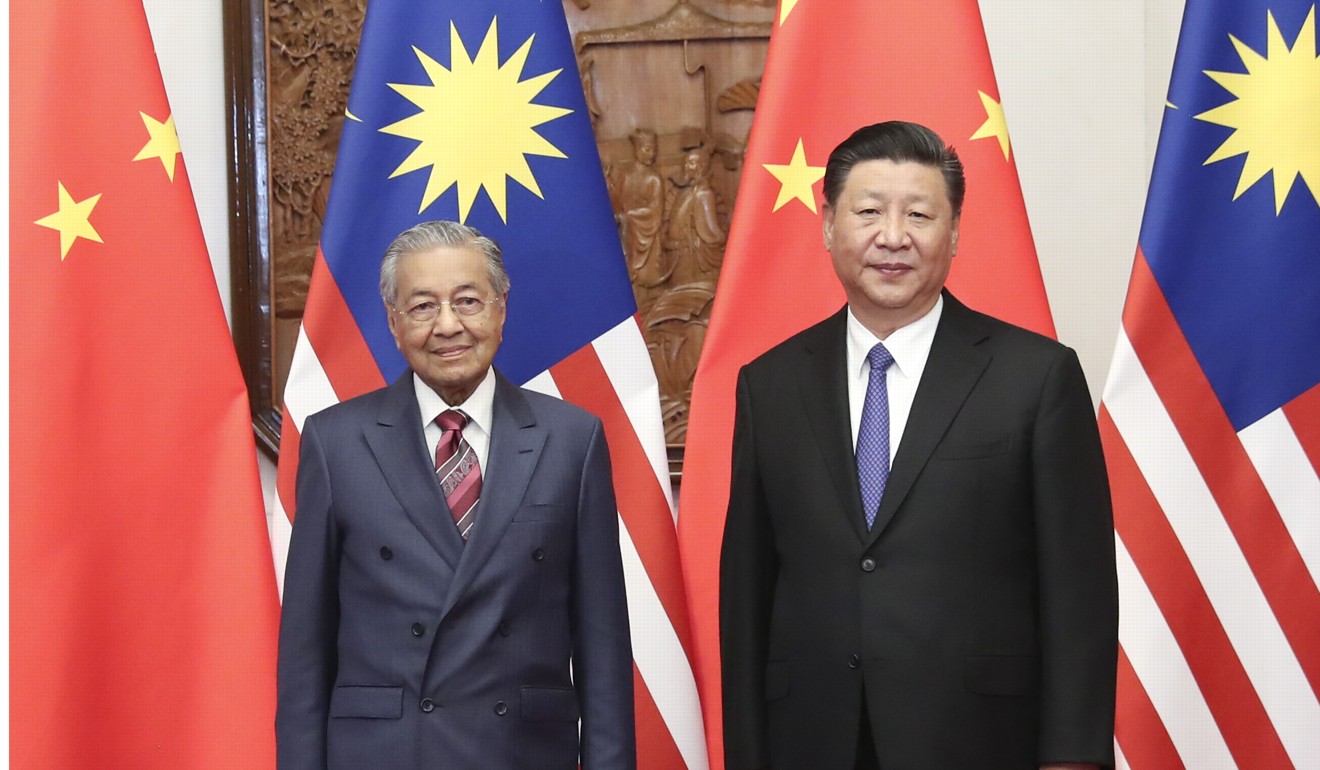

Interestingly, Mahathir announced the decision even before leaving China, and said both Xi and Premier Li Keqiang understood the reasons behind the cancellations and accepted them.

The Chinese government put on a brave face in response, with a foreign ministry spokesman saying it was inevitable there would be problems or different points of view between any two countries.

But Mahathir’s announcement has transcended bilateral cooperation, and should serve as a timely warning to the Chinese leadership about the importance and urgency with which they should conduct a comprehensive review of the belt and road strategy and recalibrate it by reining in its ambitious investment plans.

‘We like rich partners’: Malaysia’s Mahathir heads to China for fence-mending trip

Indeed, Mahathir’s decision is just the latest setback for the plan, as politicians and economists in an increasing number of countries that once courted Chinese investments have now publicly expressed fears that some of the projects are too costly and would saddle them with too much debt.

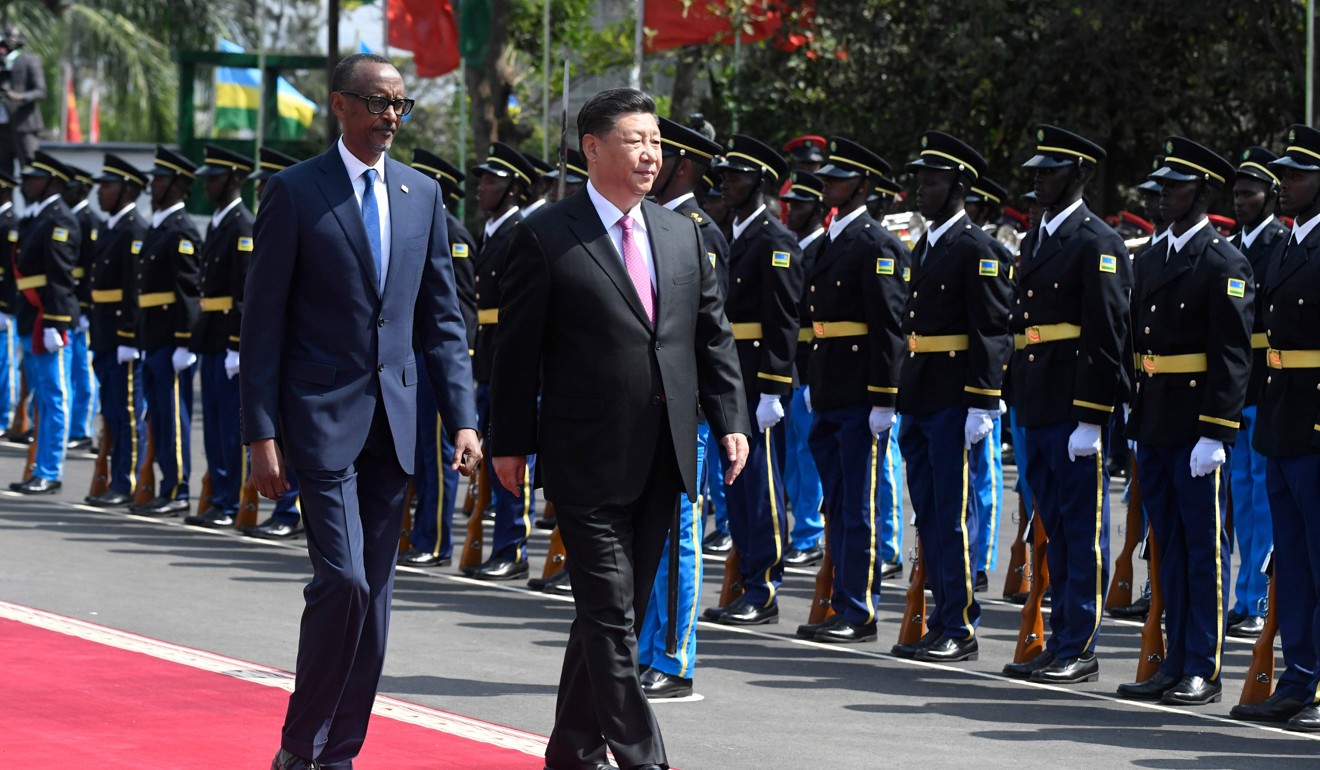

To be sure, China’s belt and road plan has been more successful in Africa, where its investments have already provided tangible benefits including the railway connecting landlocked Ethiopia with Djibouti and the Mombasa-Nairobi railway in Kenya.

From September 3, Xi will host a two-day summit of African heads of state and representatives from international organisations to discuss further cooperation between China and African countries. There is little doubt the belt and road strategy will be one of the key themes, with more investments to be announced.

It remains unclear how much money China has sent to countries involved in the plan.

Some official estimates have put its total direct investment at more than US$60 billion between 2014 and 2017, but the figure could be several times higher if loans from China’s banks are counted.

The Chinese government has been aggressively pushing the belt and road plan abroad while Xi has consolidated his power over the past five years.

Last year he declared China had entered into a new era, arguing it was never so close to the centre of the world stage.

The belt and road strategy thus appears to have become an important vehicle for China to enhance its status as a world leader.

But from the very beginning, Chinese officials seem to have bought into their own hype, overexcited about the gigantic scale and enormous potential of the plan.

Why borrowers on China’s belt and road will go from euphoria to depression

Depending on timelines and estimates, various analyses have suggested it would cover more than 65 countries with a combined population of more than 4 billion people, and would require US$4 trillion to US$8 trillion in infrastructure investments.

Realising this is Xi’s signature project, Chinese officials have struck out in all directions without much of a focus or coordination. It has not helped that the belt and road plan has become what some Chinese jokingly call a “basket” into which most of the country’s overseas investments and projects could be placed, making it difficult to differentiate them or to determine their commercial viability.

Understandably, some countries – including Malaysia – have started to worry about the commercial viability of certain China-financed projects and the impact on their domestic finances. The Sri Lankan government handed over the strategic port of Hambantota to China on a 99-year lease last December after it could not repay more than US$8 billion in loans from Chinese firms, raising questions about debt traps.

Despite their best efforts, Chinese officials still seem to fail to appreciate the political and cultural complexities in certain belt and road countries where there have been heavy Chinese investments.

Sometimes, geopolitical considerations and the determination to value the so-called special relationship have trumped sound business decisions.

The two obvious examples are China’s huge investments in Pakistan and Venezuela.

Over the past 10 years, China has reportedly sent about US$60 billion to Venezuela in one form or another, eyeing its oil supplies. But its government is faced with tremendous challenges because of political tension and economic hyperinflation, and Washington is reportedly considering sanctions.

Chinese handling of Kazakhs a bump in belt and road

The possible collapse of the Nicolas Maduro regime could pose serious risks to China’s investments in the country. Even in Pakistan – hailed as China’s all-weather friend – the latest change of government has raised concerns that some China-financed mega infrastructure projects in the US$62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor would be re-examined and renegotiated.

In a bid to reassure the international community, Chinese leaders have repeatedly said the belt and road plan was open to all participating countries along the principles of “extensive consultation, joint contributions, and shared benefits” because the initiative was not China’s solo performance but a chorus of participating countries. But in many ways, China has acted like a solo performer.

Moreover, the country’s seeming generosity in throwing big money around for belt and road projects overseas has also caused discontent at home, at a time when its economy is slowing and it faces uphill tasks such as lifting 70 million people out of poverty and making up huge shortfalls in the education and health care sectors.

Looking ahead, there are several lessons for Chinese leaders in regards to the belt and road plan’s future development. The leadership must end the current practice of striking in all directions. Instead, it must focus its money and resources on several major projects and make them sterling successes as examples for others to follow.

Secondly, on top of infrastructure projects, Chinese leaders should direct more funding to projects that would improve the livelihood of people in belt and road countries to win more goodwill.

Thirdly, they must improve transparency in these projects to ease international concerns.

Finally, the government should work more closely with international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, which have decades of experience helping developing countries. Closer cooperation with them would help China better navigate its future endeavours and make the belt and road plan more international. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper