Trump’s big button to Thai penis whitening: hail the emperor, without his clothes

The US president’s boast about his bigger nuclear button has roots in imperialism’s use of phallic domination as a tool for power projection

“I’ll liberate Africa with my penis,” declares Mustafa Sa’eed, a protagonist in Sudanese writer Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North, considered one of the most important works in Arab literature.

Sa’eed, whose life coincides with the period of British colonisation of Sudan, is a brilliant student who goes on to study in Britain, shines in academia, shows political promise in his leadership of the anti-colonial struggle, and writes scholarly tomes. But he has a fatal flaw: he uses his exotic charm to seduce English women. He destroys their lives in the process, three of them commit suicide. But for Sa’eed, it’s all for a cause – they are collateral damage in his quest to reclaim the masculinity that Sudan has lost to the British empire.

Singapore and Hong Kong may be different, but there’s no debate on what the British did to India

In his perverse conquests, Sa’eed is seeking to reverse a sexualised power dynamics that has existed between empires and their colonies, new and old. From Rudyard Kipling to Theodore Roosevelt, imperial agency has always sought to justify colonial campaigns as “manly” civilising missions, citing the coloniser’s masculine superiority as the rationale for its right to control distant lands – a well-hung empire for the well-endowed colony.

The resistance to the imperial project has also, consequently, been mostly couched in muscular terms. Asia’s freedom struggles are replete with clarion calls for men to rise and stop the rape of the motherland, a universal nationalist trope. As Cynthia Enloe puts it in her Bananas, Beaches, and Bases, “nationalism has typically sprung from masculinised memory, masculinised humiliation and masculinised hope”. Look no further than Sa’eed.

Judging empires: Was Japanese rule in Taiwan benevolent?

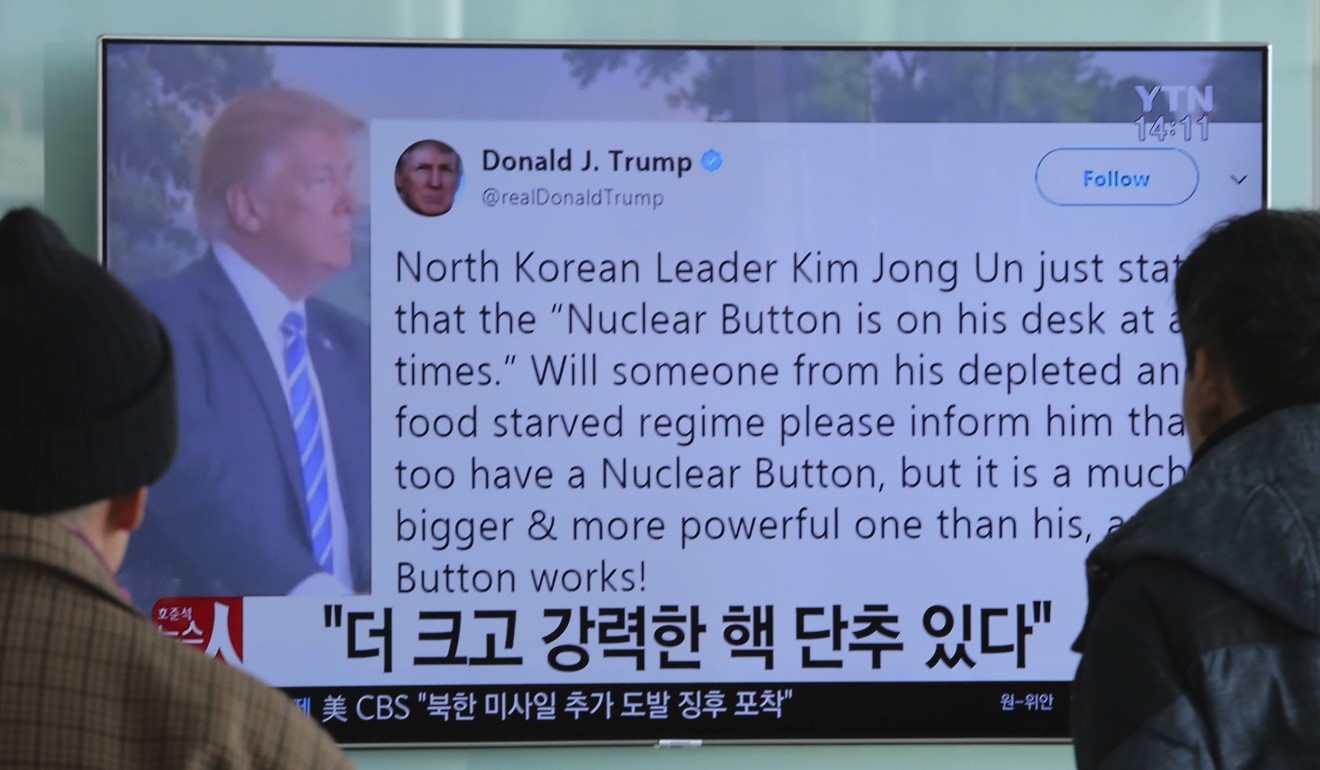

But phallic domination as a tool for power projection and control has got a lot subtler since the days of assembly-line rapes by Genghis Khan and his men, to the extent that it can go mostly undetected these days. Until its cover is blown now and then by an unsubtle practitioner such as Donald Trump, who recently tweeted that his nuclear button is “a much bigger and more powerful one” than that of Kim Jong-un, who he also fondly calls “Little Rocket Man”.

Who gained the most from Hong Kong’s colonial era: Britain, China or the city?

Trump’s thinly veiled phallic bluster has distinguished precedents in US history. When Americans began to debate if the Philippines should be set free or become a colony after the US won the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the Philippine-American War broke out the following year, Theodore Roosevelt led the imperialist argument saying: “We of America, we, the sons of a nation yet in the pride of its lusty youth … We know the future is ours if we have the manhood to grasp it, and we enter the new century girding our loins for the contest before us.” He won the debate.

Roosevelt was channelling the prevailing politico-religious consensus. Anxieties about falling male attendance in churches and fears of dwindling manliness with “overcivilised” men losing touch with nature as a result of industrialisation and urbanisation had triggered the “Muscular Christianity” movement in England around the middle of the 19th century. Churches, for the first time, began to offer physical activities such as exercise and athletics. They also called on men to engage in the then male domains of military, politics and business, imperial adventures and international evangelism. The idea was that British manhood would save the world from barbarity and the world would save British manhood from civilisation.

We’ll never forget you, Britain told Hong Kong with a straight face

Muscular Christianity reached America in the 1870s and gathered pace around the turn of the century, leading to the establishment of boys’ and men’s lodges and fraternal bodies such as the Boy Scouts of America. These organisations embodied European and American male codes of honour such as valour, drive, virility, restraint and dignity. Going forth into the world, acquiring colonies and spreading these supposed white male values was the zeitgeist of the time.

But the exercise of masculinity would vary depending on geography. In Africa, where the inhabitants were perceived as savage, justification for colonial rule would need the creation of the myth of black primal and bestial sexual appetite to contrast it with the measured, civilised masculinity of the white man. The coloniser’s control over his urges would be the rationale for his right to control the land.

Effeminate Indians, Chinese houseboys

In India, an advanced civilisation, legitimising imperial control would on the other hand necessitate the construct of the weak and effeminate native destined to be ruled by the strong, virile Englishman. Historian James Mill, for example, who wrote the History of British India – without ever visiting India – saw Hindus as possessing “a certain softness … that distinguished them from the manlier races of Europe”. For Colonel JSE Western, Hindus were “the non-fighting classes (who) never possessed the desirable virtue of courage”.

British writings of the time are particularly unkind to the inhabitants of Bengal, the nerve centre of the Raj and the site of the most extensive contact between the sahibs and their subjects. For historian and politician Thomas Babington Macaulay, who describes Bengalis as weak, timid and devoid of any masculinity, “There never perhaps existed a people so thoroughly fitted by habit for a foreign yoke.”

Hong Kong, like India, needs to remember the truth about British colonialism

Concurs journalist and writer George Warrington Steevens, “The Bengali’s leg is either skin and bone … or else it is very fat and globular … with round thighs like a woman’s. The Bengali’s leg is a leg of a slave.”

David L. Eng of the University of Pennsylvania calls this process of feminising Asian men “racial castration”, designed to perpetuate a racist and heterosexist structure to support colonial order. In the US – on its way to replace the 19th century colonial powers as the torch-bearer of western global leadership – this feminisation of Asians was to take other forms.

What China’s Belt and Road has to learn from 1920s America

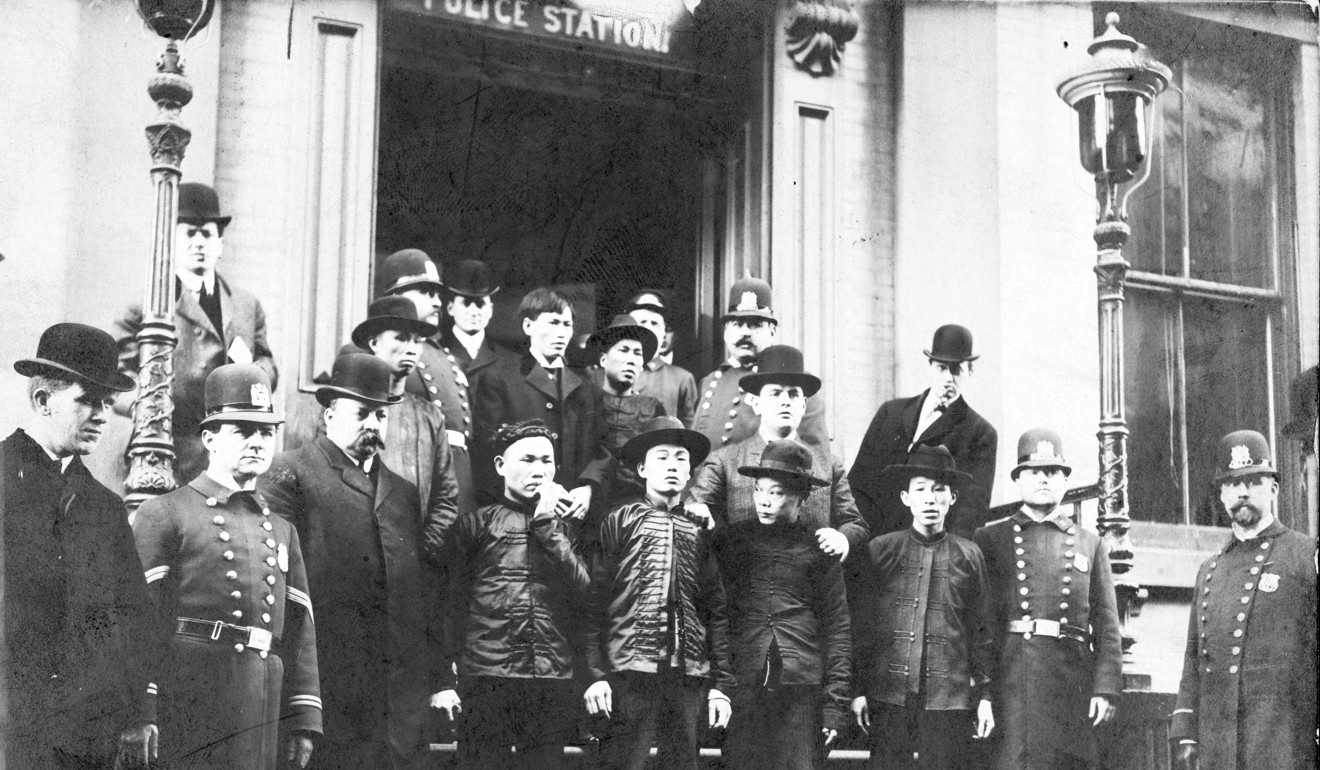

The iconic photo taken to mark the completion of the historic transcontinental railway line in 1869, for example, doesn’t have a single Chinese face in this celebrated male achievement even though some 10,000 to 15,000 of them are estimated to have worked on the project. Instead, as resistance began to grow against Chinese immigrants taking the white man’s jobs, these immigrants found themselves increasingly refused factory work and finding employment in tasks then associated with women, such as cooking, washing and cleaning. Many found jobs as houseboys. Even in 1920, half the Chinese men in the US were employed as domestic help.

To extract more work from male Chinese workers and save American employers the cost of covering the upkeep of the workers’ dependents, laws were passed to restrict Chinese women from entering the US. Only about 1,300 Chinese women were allowed entry into the US between 1875 and 1882, compared with some 100,000 Chinese men. Simultaneously, miscegenation laws mostly applied only to Chinese men, while white men could marry Chinese women.

So the enduring image of the “Chinaman” in 19th century America was a man in a ponytail either hanging around with other men in ponytails in Chinatown, or doing housework, or cooking and cleaning in restaurants.

On top of the world

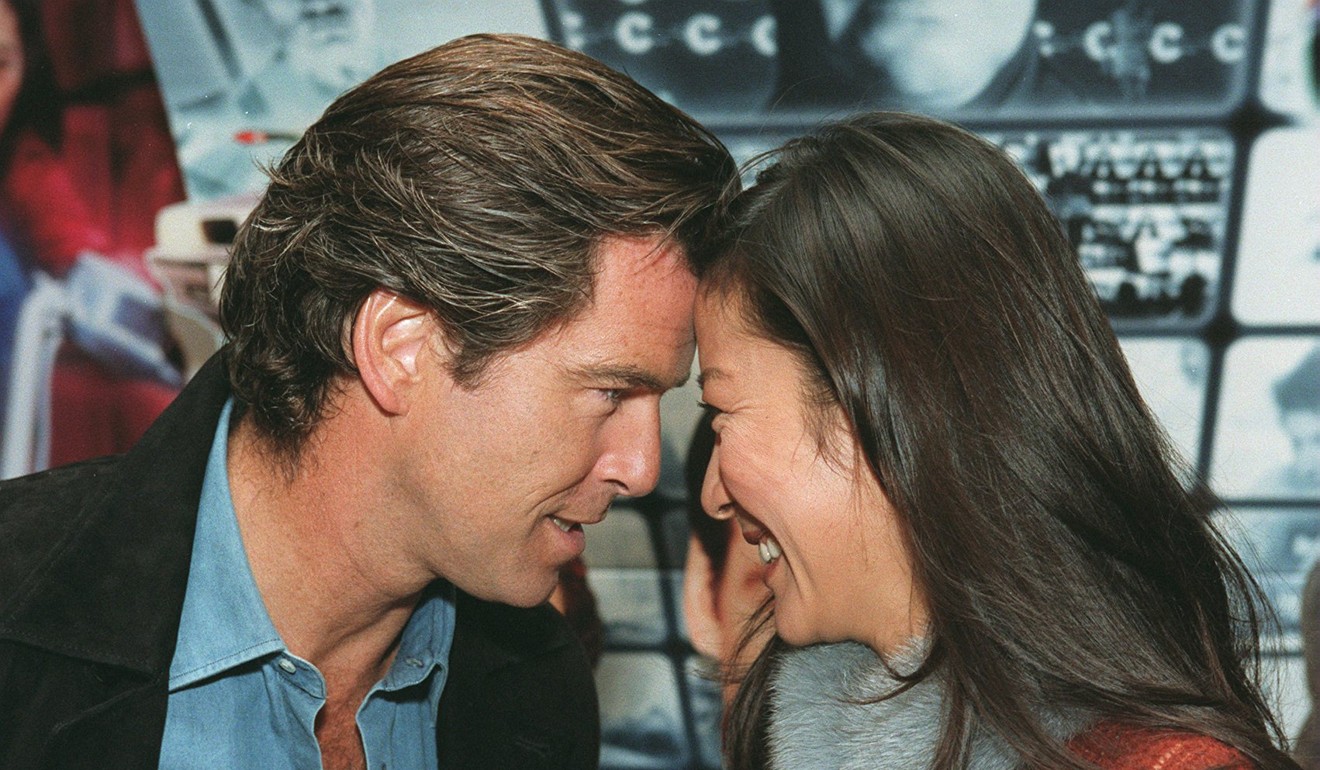

The American man, on the other hand, was moulding steel, laying railways, taming bulls, chasing bandits, fighting wars, and soon, bringing back “war brides” from countries such as Philippines, Japan, Korea and Vietnam, among others. Blissfully in love, the cross-cultural couples themselves would be unaware of the powerful political message of their pairing, especially when magnified through cinema. Even now, Hollywood mostly chooses American men and Asian women in cross-cultural pairings, the reverse is a rarity.

Along with all those manly activities, the American man was also frolicking with Asian women in the euphemistically titled “rest and recuperation” (R&R) centres around the US military bases abroad, reinforcing the notion of his universal masculine appeal. In what scholars like Sunny Woan consider white sexual imperialism, stereotypes like the submissive, exotic, hyper-sexual and gettable Asian woman and the powerful, dominant and wealthy American man trace their roots to the R&R-induced interactions during the East Asian wars. Over the decades, these stereotypes would be magnified through mass media and tourism, and internalised on both sides as a metaphor for the asymmetric power relation between America and Asia.

Prostitution to redemption: a Chinese farm girl’s journey

Take Thailand. At the peak of its alliance with the US during the Vietnam war, Thailand was home to bases for more than 750 US aircraft operating in Southeast Asia, more than 50,000 American servicemen, and major American intelligence installations. It became the launch pad of covert American operations around the region, as well as a major R&R (which American GIs also called Intercourse & Intoxication) destination. The US paid back with a gigantic economic aid programme, while GIs splashed their allowances on Thai bars, leading to a boom in the Thai tourism industry that has since become the mainstay of the country’s economy.

In Thai popular memory, as well as in much of Southeast Asia, America and the West in general thus occupy an aspirational plane, not just of financial muscle but also of libidinal power. Little surprise then that hospitals in Thailand are offering penis whitening services. Apart from Thailand, many of the clients for the service are reportedly coming from other parts of Asia. That is how deeply ingrained the binary of power and white phallus has become in the region after centuries of colonial and neo-colonial experience. As we prepare for Asia’s rise, we are girding our loins, like Roosevelt, and we won’t take any chances. We know where power flows from, and what it should look like to wield that power.

Don’t cry for me, Shinawatra: why Yingluck’s bad luck is good for Thailand

Sandwiched between the French and the English, Thailand deftly courted both powers to avoid being colonised, the only country in Southeast Asia to do so. It was just as agile in playing along with a rising US as it saw the opportunities in aligning with a new power – unlike Sa’eed, the Sudanese protagonist, who could never make peace with a dominant, alien power.

After his run of predatory relationships, Sa’eed is finally trapped into a marriage with a manipulative Englishwoman who emasculates him. He kills her while making love, is convicted and goes to jail in England, after which he returns to Sudan. There, he hides his identity and settles down as a farmer in a remote village. He meets a violent death drowning in the Nile, his painful demise in anonymity an allegory of the enduring power of the empire and the price to be paid for defying it. ■

Debasish Roy Chowdhury is the deputy editor of This Week in Asia