What makes Singaporean Malay food unique? From mee rebus to nasi lemak, historian explores the tantalising gastronomy of ‘Nusantara’ in new book

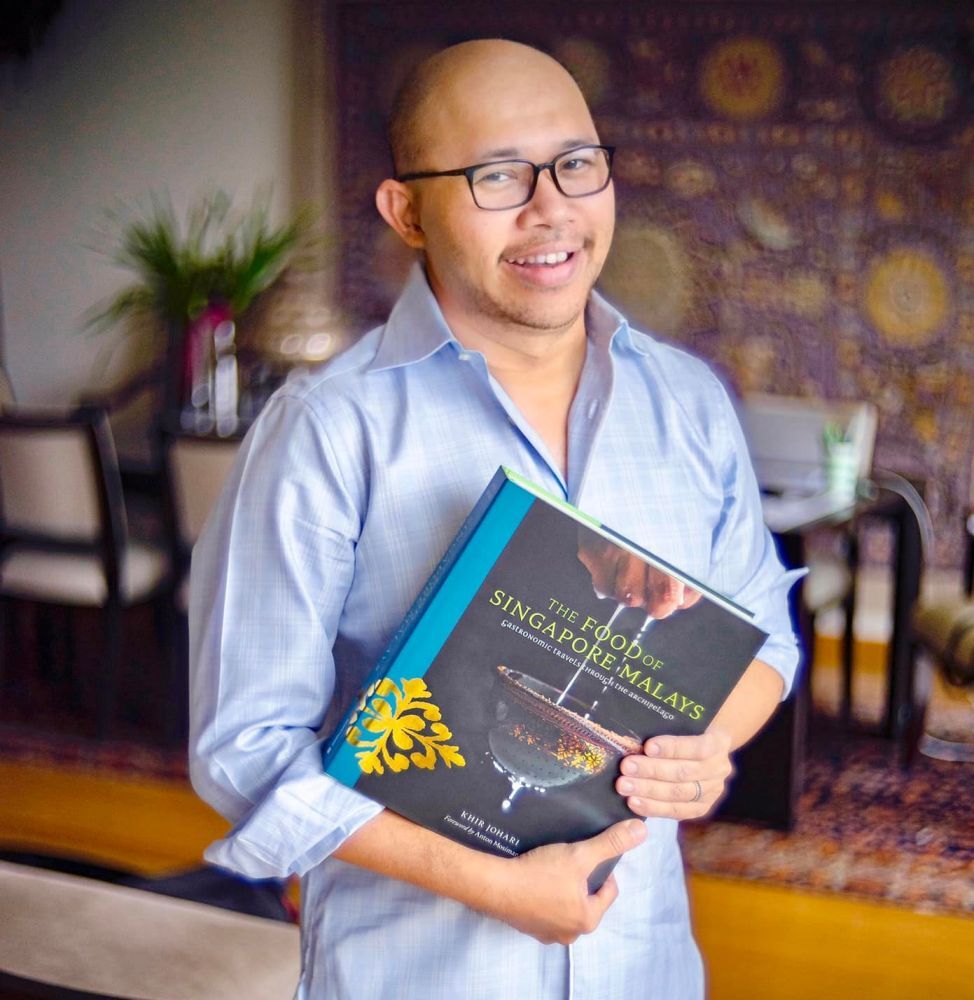

- Khir Johari unearths the complexity of Malay cuisine in his debut book The Food of Singapore Malays: Gastronomic Travels Through The Archipelago

- His collection of recipes, history, and personal anecdotes, spanning 11 years of research, explores the history of laksa, rendang and other culinary favourites

It is little wonder the cuisine’s complexity remains unfamiliar to most. Beyond the five basic tastes – sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami – there are an additional seven flavour descriptions that are unique to the Malay language.

Based on 11 years of research, the four-part encyclopedic coffee-table book contains more than 400 stunning photographs and 32 recipes for classics such as laksa Singapura, a spicy noodle dish, snacks like roti kirai, a delicate crepe served with curry, and desserts like kek lapis cempedak, a layered cake made with puréed cempedak, which is similar to jackfruit.

Khir’s passion for food began when he was just a child. Growing up in Kampong Glam, Singapore’s historic Muslim quarter, he learned from his mother the art of cooking Malay dishes.

His childhood home was the Gedung Kuning, or Yellow Mansion, a historical residence with four kitchens where his great-grandmother would prepare elaborate feasts.

Singapore-Malaysia hawker battle: who will eat their words?

But it was only in 1994 when Khir moved to the US to attend university that he began documenting Malay cuisine’s gastronomic history, scouring libraries and second-hand bookstores in San Francisco and Berkeley.

“Being part of a non-American ethnic minority made me all the more interested in my own native culture, especially when it came to cooking, eating, and dining, which are my lifetime passions,” said the 58-year-old.

“The more I read the more I realised so much of what I was discovering was not common knowledge, even among my Singaporean friends at home. The challenge was to stitch together my autobiographical memories with the broader histories of Malays in maritime Southeast Asia.”

A fear of “losing the heritage we still have” inspired him to begin writing the book, he says in its preface, after he noticed his favourites dishes disappearing such as mee maidin, yellow noodles in sakura shrimp gravy, and rujak su’un, salad mixed glass noodles in a shrimp sauce. “In order to preserve what we have, we need to document,” he wrote.

As Malay food is the result of centuries of cultural exchanges between the region and the rest of the world, many dishes have complex flavour profiles, Khir said – resulting in unique flavour categories like lemak, which describes the richness or creaminess of coconut milk.

In all, the Malay language has 12 flavour categories, more than half of which have no equivalent in English, including kelat, the astringent taste of unripe fruit, mamek, the staleness of a savoury dish with coconut, and payau, a word used to describe the brackish or briny taste of a dish.

The new faces of hunger: inflation’s human cost, from Singapore to the Philippines

With these intricacies come misconceptions, including the belief in Singapore that Malay cuisine is inherently unhealthy. Obesity rates among the city state’s Malay community are higher than among its ethnic Chinese and Indians, with a 2016 national health survey finding nearly one in four Malay adults was obese.

But Khir writes in his book that Malay food is not the culprit for these health woes. Socioeconomic factors may have led some modern-day Malays to adopt unhealthy food choices and lifestyles, but he says traditional Malay diets were based around preventing illness and maintaining health, and included a vast array of medicinal foods.

While popular dishes such as nasi lemak incorporate fried meat, vegetables remain at the centre of Malay cuisine, which features a wide range of boiled, steamed, grilled, and soup dishes, Khir said, adding that “a typical Malay meal at home consists of rice, fish, vegetables, and condiments such as sambal”.

Amid the countless debates surrounding what makes Malay food different around the region, and whether dishes like rendang belong to a single national cuisine, Khir said “it is hard to make the case that these foods are exclusively Indonesian, or for that matter, exclusively ‘Singaporean’”.

Because of Malay cuisine’s many cultural influences, such “essentialist definitions are often debatable”, Khir said. And while Singapore is home to some unique dishes such as mee rebus, yellow noodles in a thick gravy, and mee siam, vermicelli noodles in a sour-spicy gravy, others can be found in multiple places.

The origins of certain dishes may remain controversial, but for those who grew up eating it, Malay cuisine will always evoke strong feelings.

“When I’m feeling nostalgic, nasi jenganan, a simple dish served with a spicy, lightly toasted peanut sauce and vegetables, is enough to bring back warm memories of my childhood,” Khir said.