Wuhan lab’s US partner embroiled in research funding debate as Covid-19 ‘lab leak’ row rages on

- EcoHealth Alliance has been studying how coronaviruses from animals, with bats as the main hosts, could affect humans. Its work, funded by US taxpayers, has been scrutinised amid efforts to determine the source of Covid-19

- Scientists say the saga underscores the need to improve transparency around research proposal vetting, including the opaque process of peer reviews

Much of this has been due to its long-time collaboration with the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), which is located in the central Chinese city where Covid-19 was first reported in December 2019. Both organisations had collected and modified bat viruses to explore the threat of emerging diseases to humans.

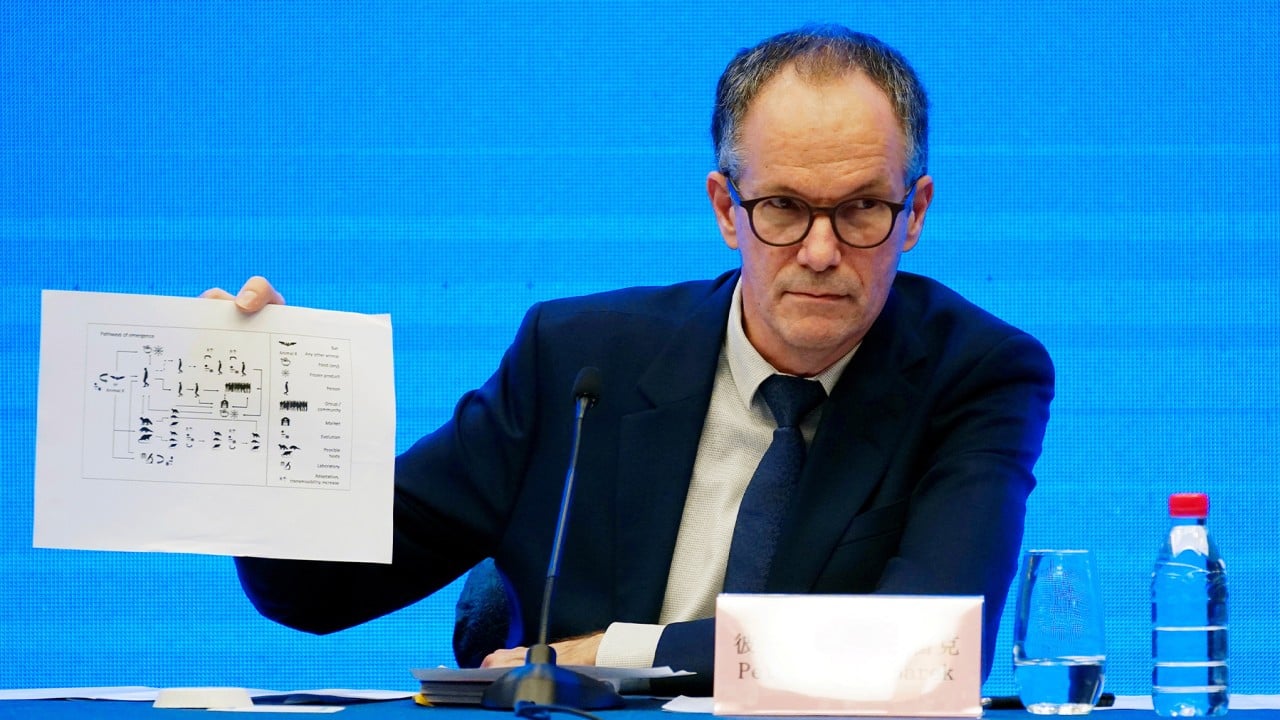

As international scientists and the US intelligence community sought to determine the source of Covid-19 – with some believing it leaked from a lab, namely the WIV, while others saying it emerged naturally – EcoHealth Alliance last year saw its funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suspended by the Trump administration.

The US medical research agency subsequently told EcoHealth Alliance that its grant could be reinstated subject to strict conditions, but the group said those would be practically impossible to meet.

Now, newly-released documents from the NIH related to EcoHealth Alliance’s funding are renewing long-standing questions about biosafety and the transparency of procedures for approving sensitive scientific research, including the opaque process of peer reviews

This Week in Asia obtained 26 pages of documents related to EcoHealth Alliance’s research project, Understanding the Risk of Bat Coronavirus Emergence, following a freedom-of-information request with the NIH.

While heavily redacted, the documents – which include scientific peer review assessments of EcoHealth Alliance’s grant proposal to study the risk of bat coronaviruses to humans – highlight the secrecy involved in approving scientific funding, while also offering a glimpse into how scientists who reviewed the non-profit’s research proposals viewed its work.

Other recently-released documents have further fuelled the unproven theory that Covid-19 escaped from a lab.

After successfully suing the NIH, US-based investigative media outlet The Intercept received and published 900 pages of other documents related to EcoHealth Alliance’s work with the WIV, specifically related to an experiment on mice. US Republicans have since used this to insist that the NIH knowingly funded “gain-of-function research of concern”, or the study of certain infectious agents by making them more dangerous.

Still, the 11 scientists that The Intercept interviewed stressed that the controversial experiment could not have directly sparked the pandemic. Neither were the viruses listed in the grant documents related to the pathogen that causes Covid-19.

The grant approval process

In the summary statements from NIH’s Scientific Review Group obtained by This Week in Asia, reviewers – comprising non-government scientists from universities and other institutes – described EcoHealth Alliance’s proposals to study the risk factors for bat coronaviruses transmitting to humans as “impressive” and “outstanding”.

“Given the Sars outbreak and current emergence of Mers in the Middle East, the significance relates to advancing the knowledge of the zoonotic potential of coronaviruses,” one summary said of the project, which received about US$3.7 million between 2014 and 2020 under a 10-year grant, before the Trump administration suspended funding last year.

The NIH redacted in full individual reviewers’ detailed critiques of the proposals, citing Freedom of Information Act exemptions intended to preserve the frank exchange of opinions during decision-making at government agencies.

Lawrence Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, said authorities should be willing to offer greater transparency without disclosing reviewers’ identities.

“Government funding should be fully transparent and open to public view,” he said.

“The public has the right to know if government funding is supporting a research activity of high public importance. The NIH need not disclose confidential information but it should provide information to ascertain whether the funding was justified and fully ethical.”

China should open the Wuhan lab – if US does the same at Fort Detrick

Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers University who has been highly critical of the NIH’s funding of research in China, said the documents indicated reviewers had not made “substantive comments on biosafety, biosecurity, or biorisk assessment” as a relevant section on “biohazards” only contained a single line of feedback.

An EcoHealth Alliance spokesperson, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said references to “unacceptable” protections for human subjects related to methodology for interviewing people, which would have been rectified before final grant approval.

“The human subject research refers to anthropological research questionnaires and the like; it’s not human test subjects,” the spokesperson said.

Several other experts familiar with the NIH’s grant approval process told This Week in Asia that no proposal would be approved before a reviewer’s criticism was resolved.

The spokesperson also denied that EcoHealth Alliance’s proposals had neglected or failed to meet biosafety standards. “The length of sections … does not necessarily directly correlate to whether they were well thought out, or well thought or well reviewed,” the representative said.

Coronavirus lab leak ‘smoking gun unlikely’ in US data trove

The NIH did not respond to a request for comment. On its website, it said confidentiality during the peer review process was “essential to allow for the candid exchange of scientific opinions and evaluations; and to protect trade secrets, commercial or financial information, and information that is privileged or confidential”.

Scientists say most of their peers agree with this approach to prevent the theft of research and allow for frank critiques of proposals.

Michael Z. Lin, a biochemist at Stanford University, said that scientists did not like to have criticism of their work publicly advertised.

“Often the criticisms are actually wrong or misinformed, so having them publicised would give an inaccurate impression of the quality of someone’s work,” he said. “Reviewers aren’t themselves peer reviewed, so what they write isn’t authoritative. Nevertheless, we need to have some gatekeeping mechanism, so peer review is it.”

A US-based microbiologist, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said greater transparency in research funding would be welcome, but most scientists would be against greater disclosure in the awarding of grants due to reputational concerns.

“The reality is most are rejected and people don’t do well with rejection,” he said. “People would find it emotionally embarrassing if their peers could see all of their grant feedback.”

‘Lab leak’ controversy

Last month, an investigation by US intelligence agencies failed to reach a conclusive answer on the pandemic’s likely origins, with four leaning towards a natural origin, one towards a lab accident, and three unable to reach a determination.

Beijing has vehemently rejected suggestions of a lab leak, with its embassy in the US describing Washington’s efforts to probe the pandemic’s origins as “doomed to be in vain because the investigation is based on fabrications and it is anti-scientific”.

The EcoHealth Alliance spokesperson said the “current body of evidence” supported a natural origin and defended the group’s research, arguing the pandemic had “shown incontrovertibly that we really do stand to only lose by not trying to get out in front of these things, as opposed to having to react once people have started to get sick”.

‘Politics hinders coronavirus hunt, but China research a top WHO priority’

Many experts have nonetheless highlighted the need for a comprehensive investigation and China’s cooperation and transparency to rule out the possibility of a lab leak.

Scientists have also raised safety concerns about future gain-of-function research, regardless of whether the pandemic could have started in a lab, an issue complicated by disagreement over the precise definition of such work.

Although the NIH did not deem EcoHealth Alliance’s project to meet the criteria for gain-of-function work under government guidelines, some scientists have argued that its research altering viruses clearly met the definition.

NIH-funded research in China included fusing the spikes of newly-identified bat viruses onto a known bat virus backbone, creating a number of “chimeric” viruses. Researchers discovered the altered viruses reproduced more quickly and caused more severe illness in genetically-engineered mice with humanised lungs, according to the documents obtained by The Intercept.

The controversy has also cast a cloud over the future of scientific cooperation between China and other countries such as the US, including studying the threat of emerging viruses and investigating the causes of the current pandemic.

EcoHealth Alliance’s work was seen by supporters as a promising example of US scientists getting a foothold in China, a coronavirus hotspot, to understand the risks and factors behind the emergence of deadly viruses.

Amid uncertainty over whether China will allow further investigations into the pandemic’s origins inside the country, the WHO last month issued an open call for experts to join a new advisory group, the Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins on Novel Pathogens, to lead the search for answers.

Yanzhong Huang, director of the Centre for Global Health Studies at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, said it was important to preserve scientific collaboration between countries, but transparency was a key concern.

“I support international collaborative research, including research that promises to improve global health security, but I think there should be greater scrutiny of such collaboration – after all, scientists may not follow exactly what they propose in the actual process of research,” Huang said.