China’s big belt and road plans for Southeast Asia hit a 10-year speed bump as ‘political side effects’ mount

- Though belt and road projects have brought economic benefits, fears are growing that the gains will prove to be ‘marginal’ amid growing debt risks

- Demand for infrastructure spending isn’t going away, analysts say – but the days of ‘paying lip service’ to local concerns in the region may be over

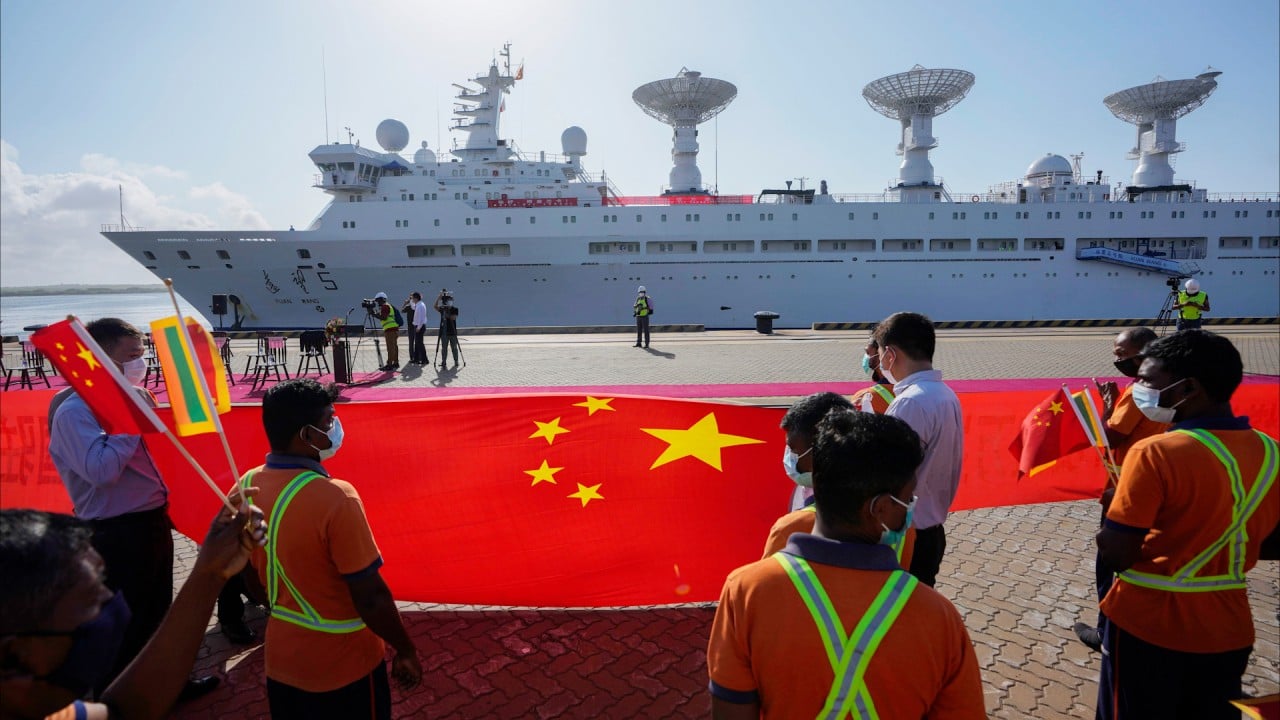

Disputes over land ownership, labour rights, corruption and environmental impacts have been some of the major points of contention with belt and road projects, according to an International Institute for Strategic Studies’ Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment released in June.

“Ethnic tensions have also arisen, with concerns sometimes voiced by local populations that Chinese workers on belt and road projects have received higher pay,” it said.

‘Growing hesitancy to accept China’s money’ could trip up belt and road in Southeast Asia

Nur Rachmat Yuliantoro, an associate professor of international relations at Gadjah Mada University in Indonesia’s Yogyakarta, said that even though belt and road projects had brought some economic benefits to the region, fears were growing about social instability and debt risks.

“The lack of raw materials and local workers has also raised concerns about the marginal dividends from the belt and road process,” he said, adding this was compounded by unclear bidding procedures, geopolitical concerns, and a dearth of predictability surrounding projects.

“These political side effects could negatively impact future collaborations with the Belt and Road Initiative and China” and push Southeast Asian nations to build relationships with other international partners instead, he said.

Nearly 60 per cent of China’s overseas loans are now held by countries considered to be in financial distress, the Maybank report said, compared to just 5 per cent in 2010 – with rising interest rates and inflation only increasing debt risks. In Laos, for example, public and publicly guaranteed debt owed to China was 27.8 per cent of the country’s entire gross domestic product in 2021.

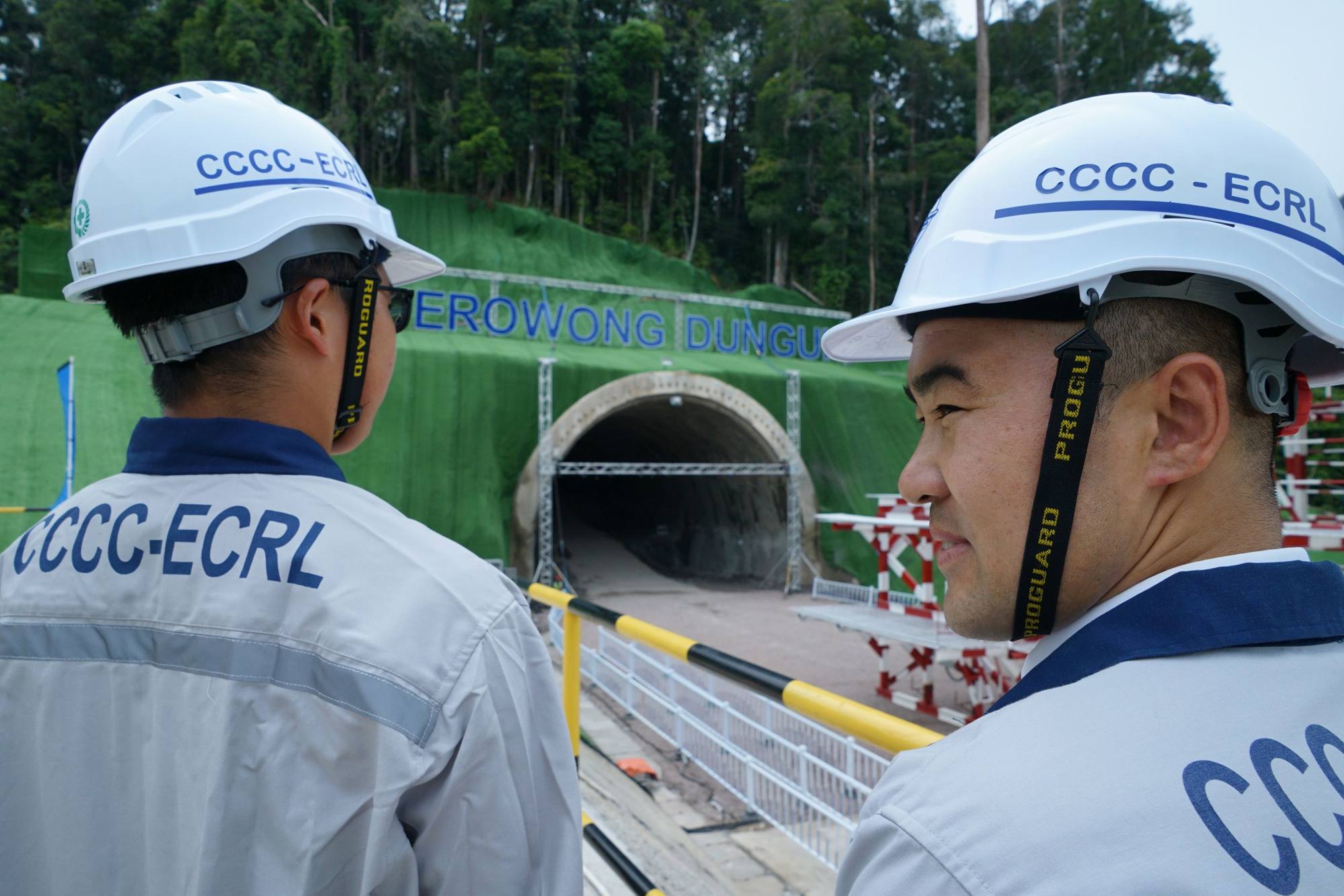

“He raised with both his China counterpart and the large Chinese investors the need for ‘upskilling’ Malaysian workers and for technology transfer,” Oh said.

Instead of a “transformational game changer for their livelihoods”, most ordinary people in recipient countries viewed belt and road projects as “objects of curiosity similar to Disneyland rides”, he said.

Imported Chinese labour was another issue, Oh said, as these workers were often preferred by Chinese companies over local hires to ensure belt and road projects are built “as fast and as smoothly as possible”.

Benjamin Barton, an associate professor of international relations at the University of Nottingham’s Malaysia campus, said that the belt and road “business model” was built on using Chinese subcontractors, recruiting Chinese labourers to work long shifts comparable to those they would at home, a reliance on materials produced in China and securing financing from Chinese policy banks.

Some countries have tried to impose quotas on the recruitment of local labour, but enforcement is often patchy, Barton said, as it can be “cheaper” for companies to resort to bribery than uphold the law.

On a day-to-day basis, there have been growing concerns over the financial viability and general added value of belt and road projects

Demand is also growing for the terms of previously signed deals to be revisited and the granting of repayment period extensions, but Barton said these are largely being negotiated at the highest levels of office.

This sprawling project, just across the water from Singapore, has witnessed sluggish sales – being described by some as a “ghost town” – amid Chinese currency controls and public anger at Beijing’s growing influence in Malaysia.

While the project resumed development last year, local communities have this month called on developers to apply for a new environmental impact assessment to identify the project’s impact on a shoreline that is vital to many fishermen’s livelihoods.

Countries mainly took on such projects to meet development objectives or fulfil specific political promises, Barton said, with short-term financial dividends not necessarily a primary concern.

“That is why there will be continued interest in belt and road projects across Southeast Asia, where there continues to be an investment deficit in infrastructure,” Barton said, pointing to the three logistics and infrastructure agreements signed by Anwar in China’s southern Nanning city last week.

But there will also be “a significant push for projects which fare better at protecting the environment and demonstrating their sustainability credentials”, he said, noting that “the age of just paying lip service” to local concerns “is quickly dissipating”.

China realises small is beautiful as Belt and Road Initiative turns 10

Since 2017, Beijing has highlighted the need to improve environmental management of its belt and road investments after acknowledging that sustainability had emerged as an essential component of the giant connectivity push, recognising the challenges its projects were facing overseas.

Upon its launch at the G7 in 2021, the US-led programme promised to provide – with help from the private sector – some of the US$40 trillion in infrastructure that developing countries are forecast to need by 2035, operating as an alternative to China’s belt and road for low and middle-income countries.

Washington’s plans have emphasised what Han calls the “software” – cooperation on climate, healthcare, digital governance and gender equality, for example – as opposed to the “hardware construction” of belt and road infrastructure projects.

“In the next 10 years, based on its achievements, the Belt and Road Initiative should consider pivoting to these areas with investments which can benefit people more directly,” she said.

Between 2013 and 2015, most belt and road projects centred on transport and energy infrastructure, the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ June security report found, but started to include more special economic zones and trade agreements from 2016 onwards.

The US and some of its allies have framed China’s “tailor-made belt and road collaboration model” as a neocolonialist “debt trap” that was “damaging the climate”, Han said.

“This issue needs to be addressed through more dialogues and communications with the local community to make the Belt and Road Initiative not only Chinese, but also part of the local community’s development initiative.”

A Western-led challenge to China’s belt and road? Not so fast, analysts say

Jon Yuan Jiang, an independent Australian-based PhD scholar and international-relations specialist, said regional governments were likely to start negotiating harder for more local workers to be involved in the construction of future belt and road projects, given the limited economic benefits the host country enjoys during this phase.

They may also weigh the costs of such projects more closely than before and “seek more favourable loan terms or explore alternative financing options to alleviate debt burdens”, he said.