Who pays when Indonesian ride-sharing fraud goes full throttle?

Drivers are using various techniques, including fake GPS apps found on the dark web, to inflate their numbers and get undeserved bonuses

Ignasius Yoesrandewanto, a driver with Indonesia’s ride-hailing giant Go-Jek, was waiting for work recently at his usual spot in a bustling railway station in Jakarta when he got a request that would seem quite a challenge for the 34-year-old scooter operator.

He was asked to deliver a locomotive.

“I cancelled the order right away,” Yoesrandewanto told This Week in Asia. “You know it’s fake.”

The story may be worth a chuckle, but such bogus auto-bid requests matter to Yoesrandewanto’s bottom line, as bonuses are based on a driver’s performance and completion rates.

What Uber needs to do to catch up with Asian rivals

At Go-Jek, for example, two-wheeler drivers must complete at least 60 per cent of all bookings per day to receive a maximum bonus of 200,000 rupiah (US$14). For drivers with Singapore-based Grab, Go-Jek’s main rival, the cancellation rate must be below 10 per cent.

“Fake orders are hurting my income. With Go-Send we wouldn’t know what kind of stuff that we have to deliver before we accept the order,” Yoesrandewanto said, referring to Go-Jek’s small parcel delivery service. “In 24 hours I got two or three fake orders, that means I have to cancel these bookings and that would affect my performance.”

Fraud is widespread in Southeast Asia, and Indonesia seems to lead the pack. According to a recent survey by Jakarta-based Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (INDEF), 61 per cent of ride-hailing drivers – two- and four-wheelers – in the region’s biggest economy know other drivers who have conducted fraud. More than 80 per cent of drivers receive fake orders on a weekly basis, and one out of three drivers see it every day. In Southeast Asia, up to 20 per cent of all rides are fake, according to Grab.

Singapore’s oBike gets on its bike: proof you can ‘kill your innovators’?

“Drivers cheated because they weren’t afraid to get caught and they wanted to get the bonus without having to work for it,” says Berly Martawardaya, programme director at INDEF. “The ride-hailing companies’ detection [system] is still weak so many drivers think it’s safe for them to cheat because only a few drivers are caught.”

To fight this trend, Grab and Go-Jek revamped their anti-fraud tools in recent months. These campaigns are also closely monitored by investors as a way to gauge, among others, the value of the companies, a source within the industry said. Go-Jek, particularly, will have to show that it can tackle fraud in home market Indonesia before expanding to other Southeast Asian countries. The company, valued at US$5 billion, has set aside US$500 million to expand to Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines.

INDEF’s survey showed that 42 per cent of drivers said Go-Jek had the most fraud, compared with Grab’s 28 per cent.

“Once a friend told me about a fake GPS [app], but I don’t want to use it because that means I would lie to the customers,” says Dramendra Radiasi Gultom, a two-wheeler driver with Go-Jek, referring to drivers creating fake orders.

No free ride for Singapore’s Grab after Uber exits Southeast Asia

The region’s ride-hailing fraudsters might be inspired by their predecessors in China. Cheaters were rampant there when Uber battled the country’s ride-hailing behemoth Didi Chuxing. The fraudsters were enticed by Uber’s high bonus payouts, which could reach up to threefold of drivers’ official fare earnings. Uber sold its business to Didi in 2016.

Old game, new players?

Aside from the GPS app, Indonesian drivers often set up fake driver and rider accounts, or buy one at myriad computer stalls in Jakarta’s malls, sold for up to 1 million rupiah. This allows them to create their own ride bookings and pretend to finish the trips to hit incentive marks.

Another method is called “cash default”, in which a driver uses a fake account and only accept rides from passengers that pay in cash. For the tech-savvy fraudsters, they would use the unofficial version of the apps and modified phones that enable them to bypass root and mock location detections, as well as to cancel rides without consequence. On the dark web, there are at least 1,300 unofficial versions of Go-Jek’s app for Android, compared with three of Grab’s, a person familiar with the matter said.

“A very sophisticated syndicate in Indonesia used an unofficial [Grab] app so that they can cancel as many times as they like,” says Wui Ngiap Foo, head of user trust at Grab.

In the ride-hailing industry, fraud schemes vary throughout Asia. Drivers in India use the so-called surge-pricing method, simultaneously going offline at popular spots to trigger false demand. Once fares go up, drivers get back online.

In Malaysia, drivers often tell customers they will accept lower fares in cash, under the table, if passengers cancel the booking, because it allows the driver to pocket the fare without giving a cut to the company.

Law enforcement is caught in a game of whack-a-mole in its efforts to curb fraud. Police in Indonesia’s Central Java province recently busted a group of eight cheating drivers that had earned at least 6 billion rupiah (US$418,000) from placing phantom rides on Grab. This group used 53 fake driver accounts and 213 Android smartphones to place the orders every day. In Jakarta, police busted a syndicate of 12 Grab drivers that carried out fake orders for at least three months, costing Grab 600 million rupiah. (US$42,000).

Fighting the fraud

Grab and Go-Jek have recently strengthened their anti-fraud campaigns and detection tools to fight phantom rides, particularly in Indonesia where cheating is more prominent. Grab introduced a whistle-blower programme called “Fairplay” that has generated 9,000 tips and led to 10 busts of illegal syndicates across Indonesia. The programme, it said, has led to an 80 per cent reduction in fraud in the past 12 months.

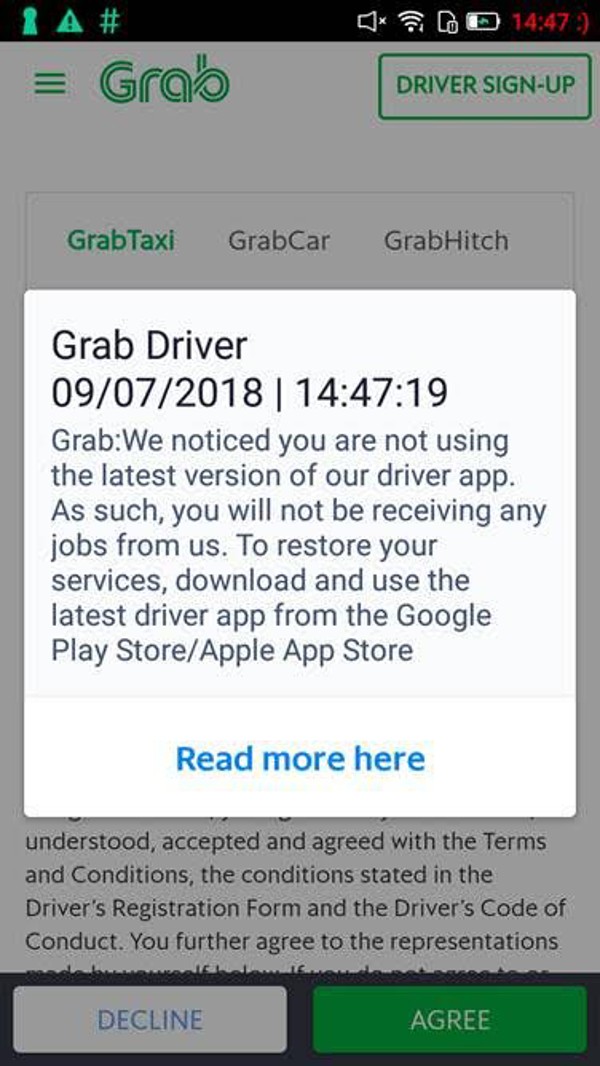

As for Go-Jek, the company in April launched a detection tool that would warn drivers via a pop-up notification if they use fake GPS applications.

Who can grab the opportunity as Uber’s Asian ride gets bumpy?

“Until June we have sanctioned hundreds of thousands of drivers and customers that were involved in placing fake orders,” says Michael Say, vice-president of corporate communication at Go-Jek. “Our system detects that over 80 per cent of phantom rides are concentrated in specific areas and hours, leading us to believe that this is done by irresponsible parties whose mission is to bring over fake rides to Go-Jek platform.”

Some drivers, like Yoesrandewanto, welcome the tighter security. Still lacking, however, is the server’s ability to self-filter orders on small cargo delivery services, which is available on Grab and Go-Jek’s platforms.

“The security is tighter, I have received fewer fake orders now compared to before,” says Yoesrandewanto. “But I hope Go-Jek’s server could filter ridiculous orders for Go-Send, if they could read ‘ghost’ ride orders then they also need to be able to detect items that don’t make sense, like sending a ‘refrigerator’ via Go-Send. It shouldn’t be able to make it into the system.” ■