China reliant on US core technology for some time, but so is the world

America's unassailable lead in semiconductor manufacturing is the dividend from over 50 years of research and development

As the so-called ZTE incident enters the next phase, the line coming out of China has changed from bravado to humility. The Global Times lamented the “huge gap” in technology that would require “generations of arduous efforts to overcome”, while the Communist Party's Beijing Daily said China was “not amazing” in certain areas, a tongue-in-cheek reference to a recent propaganda film called Amazing China. Separately, a Tsinghua University professor was quoted by The New York Times saying China’s prosperity was “built on sand”.

While the statements from state-controlled media could be clever attempts at downplaying China’s strengths in the face of escalating trade tensions with the US, the professor’s comment is factual – technically speaking.

Not only China’s, but the world's prosperity is built on sand. That’s because it is the raw element used in the production of silicon, the base material for most semiconductors, commonly known as microchips.

Semiconductors are China’s biggest import by value – exceeding even crude oil. Clearly, silicon is its technology Achilles’ heel despite decades of efforts trying to catch up to the west.

The US has been reaping the silicon dividend for more than 50 years, ever since transistor co-inventor William Shockley moved to California in the late 1950s to start a company to perfect the process of manufacturing silicon-based transistors. In doing so, Shockley was the one who put the “silicon” in Silicon Valley.

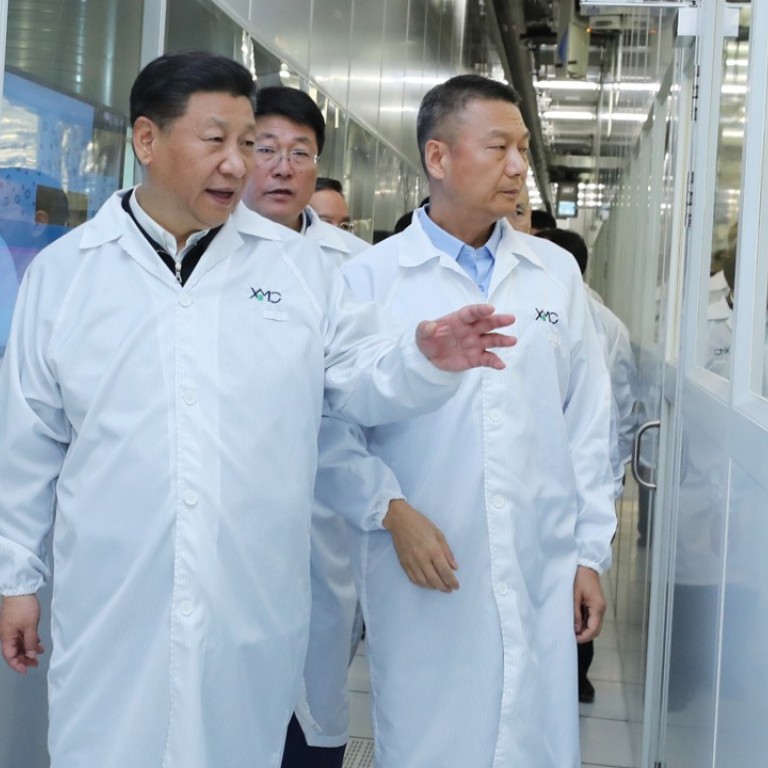

When the US first imposed a seven-year ban on ZTE buying its products, an act that crippled the telecoms giant and is still unresolved despite intervention by US President Donald Trump at the request of Chinese President Xi Jinping, there was a rising chorus of voices, led by Xi himself and taken up by tech company leaders like Tencent’s Pony Ma, calling for the country to become self sufficient in core technologies.

This call to action is nothing new. In the 1990s billions of yuan were invested into new semiconductor fabrication lines using technology (legitimately, in this case) transferred from foreign chipmakers, only to find that these “wafer fabs” – that can take two years to build from scratch – were outdated on day one because the state of the art had moved on.

Efforts by China to obtain US semiconductor trade secrets through legitimate acquisitions have also mostly failed, with Washington pushing back on national security grounds.

The biggest one that never happened was when Tsinghua Unigroup offered US$23 billion for US memory chip maker Micron Technology in 2015. The offer was turned down, but it was never likely to have received Washington’s approval anyway.

China tech boosters like to point to the Kirin phone chips designed by Huawei Technologies, the world’s No 3 smartphone maker, as an example of a Chinese company wisely reducing its dependence on foreign core technology – in this case US phone chips from Qualcomm, whereas Huawei’s rivals Xiaomi and ZTE still have to buy them.

The recent sale of a controlling interest in Arm’s China unit, giving the Chinese investors access to the UK company’s semiconductor IP, is cited as another success on the road to core tech independence.

If China’s long term goal is to develop its own core technologies to lessen dependence on a geopolitical rival like the US, acquiring chip design skills is only the first step. It also needs an indigenous semiconductor manufacturing industry – and doing that is far more difficult.

The problem is that Huawei doesn’t manufacture its own chips – nor does Qualcomm for that matter. They outsource this very complicated and capital intensive process to independent silicon wafer foundries.

The dominant foundry by far is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (TSMC), which had a 56 per cent share of total industry revenues in the first half of 2018, according to TrendForce. It is the principal foundry for Huawei’s Kirin and Qualcomm’s SnapDragon chips.

The next closest player, Singapore-US outfit GlobalFoundries, represents under 10 per cent of the market. The biggest mainland Chinese foundry, SMIC, has under 6 per cent – and in 2009 agreed to transfer 10 per cent of its shares to TSMC as part of a settlement over an earlier IP theft case.

While Huawei’s loyal smartphone users may take some comfort from thinking the company didn’t make the same “mistake” as ZTE by relying on US phone chips, they may be surprised to learn that the wafer foundries that fabricate Kirin chips mostly rely on equipment from US companies.

Applied Materials, KLA-Tencor and Lam Research – all based in Silicon Valley – accounted for more than 55 per cent of the so-called front end wafer fab equipment market in 2017, according to The Information Network. Japan’s Tokyo Electron and Europe’s ASML together took 38 per cent.

So Huawei, like ZTE, still relies on core US technology – as does every company in the world that uses silicon in its products.

The technology developed over the decades by Applied Materials and its Silicon Valley peers can be directly traced back to Shockley's laboratory, where engineers used crude but commonly available items like kilns, drill presses and glass tubes to try and produce workable silicon devices.

It is not as if China is completely defenceless. The country has a lock on the supply of rare earth materials which are critical for many electronics applications. And it can swap technology for access to its large, growing market – though this tactic is one of the major causes of friction with its western trading partners.

Given that China, like the rest of the developed world, will rely on US core technology in semiconductors for the foreseeable future, Beijing may have little choice but to play by global trade rules. It would also be prudent to commit more funding to original research and development in semiconductors – but without the bravado. Like Deng Xiaoping said: “Hide your strength, bide your time.”

The author is a technology news editor with the South China Morning Post. From 2002 to 2009 he worked for SEMI, the Silicon Valley-based trade group representing semiconductor equipment and materials companies. Follow on Twitter @craigaddison