Booing fans and failing teams hint at China’s football future after a year of ‘irrational investments’ and underachievement

The investment and spending frenzy may be over for now, but China’s soccer strategy is still pushing forward

This creep is not, however, just characteristic of China’s relationship with Hong Kong. A recent extended article in Britain’s Financial Times observed how China’s next wave of investments is intended by Beijing to result in the development of “football with Chinese characteristics”.

This was always China’s intention, though the country has often struggled over the last two years to match its football vision with an appropriate strategy.

If the Chinese government really does hold out any realistic hope of winning the World Cup by 2050, then the clock is ticking. The generation of youngsters now playing football in schools will be in their early-30s by the time we get to 2040. To build and sustain subsequent generations of elite professionals will be a major task.

In recent weeks, China’s national team has once again showed how far it is behind its international rivals. Back-to-back home defeats by Serbia and Colombia (neither of which are currently ranked in Fifa’s top-10) illustrates how much work China still has left to do.

As if further evidence was needed of China’s pressing need to develop talent and build winning teams, its Super League failed for the second consecutive year to get a team into the Asian Champions League final.

However, with Guangzhou Evergrande (GE) having won the tournament twice (in 2013 and 2015), China’s failure to win further subsequent iterations of the tournament sends out an unfortunate message about Chinese football to the rest of the world, and at just the wrong time.

There is clearly an issue of competitive balance for them to address; it is counterproductive for GE to be dominating domestically but failing internationally. Furthermore, whilst other Chinese clubs (like Shanghai SIPG) have become stronger, many wonder whether they are strong enough to compete or whether they can sustain a challenge to GE. One response of China’s authorities to the issue of talent development, competitive balance and, linked to this, league structure, has been to redesign some of its lower leagues.

Following the National Congress in October, the messaging coming out of China is that such investments are no longer acceptable, and that those making them should focus their attention back towards China (and Chinese football). As such, proposals have been made to further regulate outbound investments, which will potentially impact upon both football and industry in general.

To further complicate matters, rumours have continued to circulate that existing overseas investments will be ‘called-in’ by the Chinese government. This has been especially concerning for fans of Italy’s AC Milan, with some observers speculating that the club’s Chinese owners will be forced to sell their asset and repatriate the funds back to China.

Despite the signals coming out of Beijing, many football fans across the world remain hopeful that a Chinese investor will rescue their respective clubs. For the time being, this seems to be a forlorn hope, though there is evidence that China remains active in the sector. Notwithstanding investment controls, there have been recent reports that Premier League Chelsea’s stadium redevelopment project will be funded by a Chinese investor.

Whether this is the case will remain a moot point for the time being. However, Chelsea’s location in an affluent part of London means the real estate value of any cash injection that a Chinese investor might make in the club would be considerable. Indeed, resultant currency flows back into China would make this an attractive proposition for the country’s state regulators.

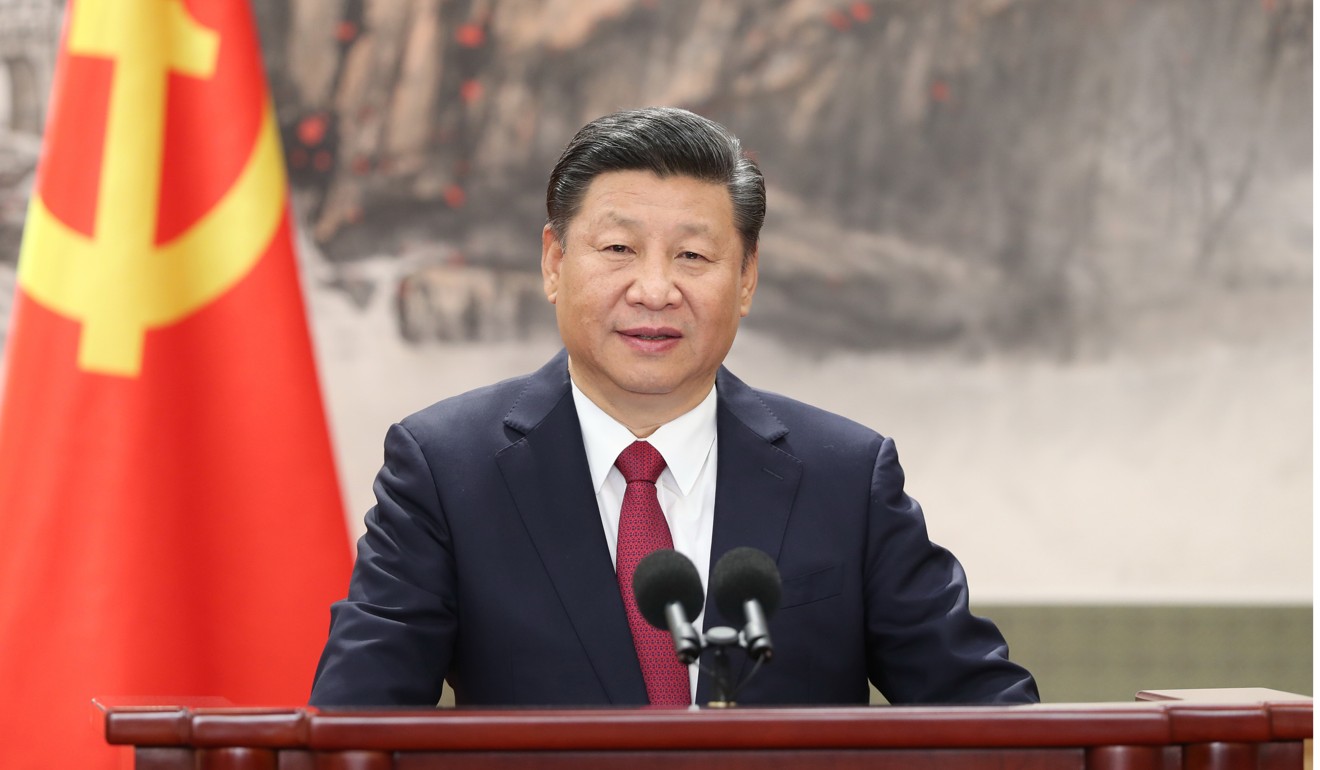

And this is what we should all now accustom ourselves to. President Xi and China’s legions of investors were never going to be football sugar-daddies. However, this year’s events have brought clarity and cohesion to our understanding – and China’s too – of what happens next in football.

This piece is published in partnership with Policy Forum.net, an academic blog based at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy.