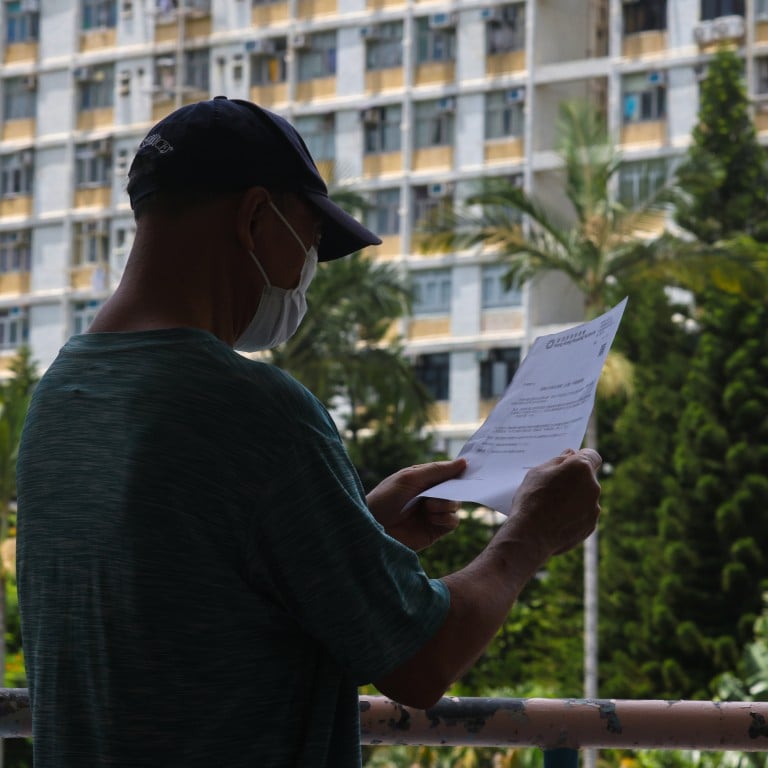

Former Kowloon Walled City resident trying to take Hong Kong government to court over fourth rejection of public housing application

- Retiree files application for judicial review over policy barring him from public housing after he accepted compensation 30 years ago when his flat was demolished

- ‘He is 74 and unable to find any more work due to his age and arm injury. We feel that as an elderly resident, he should have a roof over his head,’ NGO says

A former Kowloon Walled City resident is trying to take the Hong Kong government to court after his application for public housing was rejected four times, contesting an eligibility clause that bars him because he accepted compensation when the area was demolished.

The retiree surnamed Hui filed an application for judicial review and accused authorities of “unfair treatment” over a policy that made him ineligible for government housing because he had accepted the financial package 30 years ago when his home in the Kowloon Walled City was knocked down.

“They reject me for the same reason every time, so I have no choice but to appeal through legal means,” the 74-year-old said.

Those who accepted the money are considered to have opted to make their own accommodation arrangements under Housing Authority guidelines and cannot apply for public rental flats.

Inside Kowloon Walled City: ‘I knew I was somewhere extraordinary’

But those reimbursed because of more recent redevelopment projects or clearance of squatter areas can apply for two years after receiving payment.

Hui accepted the deal in 1993 and received HK$70,000, the equivalent of HK$131,237 (US$16,750) today, as compensation for the demolition of a 250 sq ft (23.2 square metre) flat he co-owned with a friend in the 1980s.

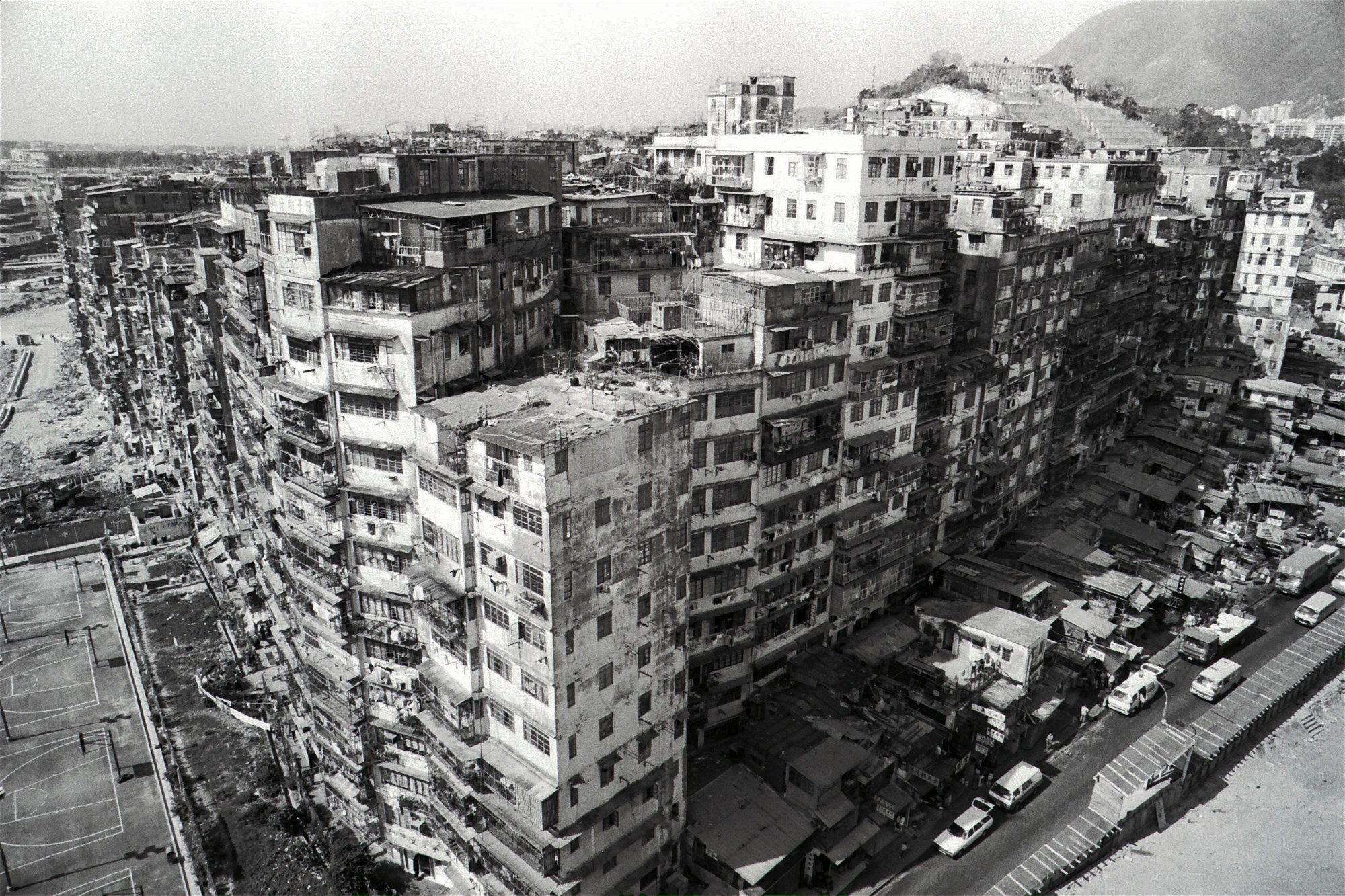

The walled city was a densely populated enclave near the former Kai Tak airport that spanned 2.7 hectares (6.67 acres). The area was infamous for its opium parlours and gambling dens run by triads before it was knocked down in the run-up to Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997.

The government offered residents the chance to relocate to public housing or be compensated the market price for their flats.

Hui said he and his friend had decided to split the HK$140,000 on offer.

“I chose to buy a unit in the Walled City precisely because they were cheaper due to the difficult environment. Flats on the market then cost HK$200,000 to HK$300,000, so HK$70,000 could not buy me anything,” he said.

Hui worked as a dim sum chef after leaving the enclave and was offered free accommodation with the job. He later switched to renting a subdivided flat in Yau Ma Tei when he became a security guard.

A look back at life inside Hong Kong’s Kowloon Walled City

But a workplace injury in 2019 left him unemployed and living on the streets before the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO) offered him a temporary place to stay and support to apply for public housing.

“He is 74 and unable to find any more work due to his age and arm injury. We feel that as an elderly resident, he should have a roof over his head,” said SoCO community organiser Ng Wai-tung, who is helping Hui apply for legal aid.

“The Housing Authority doesn’t have an appeal system, so we are taking this to the High Court, because we have exhausted all appeal procedures.”

Hui also receives financial support from the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) scheme for Hongkongers with assets of less than HK$35,000 and is at present staying at a transitional housing flat, but must leave after two years.

He said he felt the rejection of his public housing applications was unjustified because authorities still accepted those who had bought subsidised housing, but later faced circumstances such as divorce, bankruptcy or other financial hardships.

“I applied for CSSA thinking that I could apply for public housing through this exemption, but they still rejected me because I previously received compensation from the government and will not be eligible for any more subsidised housing,” he said.

“That is very unfair.”

The Housing Authority declined to comment as legal proceedings were under way.

Ho Hin-ming, chairman of the Kowloon City district Council, said giving Hui an exception to the policy would be unfair to other walled city residents who received the compensation, including those who decided to buy subsidised housing.

Remembering Kowloon Walled City

Ho, who heads the council’s Housing and Infrastructure Committee, said during a 2005 meeting on relaxing the eligibility for these residents that they could turn to other social welfare mechanisms if they needed assistance.

He recommended the Housing Authority review the number of times and conditions under which Hongkongers could enjoy housing benefits, to maintain a fair and reasonable system.

“If he had received incentives from one department before, he shouldn’t be able to receive it again,” Ho said. “If applying through the Housing Authority doesn’t work, he could try applying for compassionate rehousing through the Social Welfare Department, as every department works differently.”

Compassionate rehousing is a form of special housing assistance that provides assistance to those with “genuine and imminent” housing needs but have no other place to turn for help. Applicants must be assessed comprehensively by social workers.