Opera, gangsters and swordplay: the rise and fall of Hong Kong cinema

- Once known as the Hollywood of the East, the city’s cinema has taken a hit in recent decades, with imported Hollywood films besting local fare at the box office

It could be the dreamy neon-drenched images that won Wong Kar-wai a Lumière, or maybe it’s the kung fu magistery of Bruce Lee that come to mind when one thinks of Hong Kong movies. Regardless of what precisely it might be, it is undeniable that the city’s cinema once captured hearts worldwide, propelling local idols onto the international stage.

As a British colony, Hong Kong’s political and economic freedoms set it apart from mainland China and Taiwan, allowing it to supplant Shanghai’s cinematic supremacy by World War II, and eventually become the centre of Chinese-language filmmaking.

For decades, Hong Kong was Asia’s movie capital, dubbed time and again as the “Hollywood of the East”. Recently, however, tales of Hong Kong’s once thriving motion picture industry are sombre stories explaining its decline.

This week, City Weekend explores the long and colourful history of cinema in Hong Kong – its birth, its growth, and whether it is really, as suggested by some, a dying industry.

The rise and fall of Hong Kong showbiz ... and how fans still hold on to yesteryear

How did it begin?

For centuries, opera was the primary form of dramatic entertainment in the Chinese-speaking world. It is no surprise, then, that the beginnings of Chinese cinema, pioneered in the early 20th century by Liang Shaobo and Lai Man-wai, were intricately tied to this culture.

As sound came to the cinema with the “talkies”, filmmakers had to reckon with differences in language for the first time. In 1932, the Shaw brothers worked with Cantonese opera star Sit Gok-sin to produce the first Cantonese talkie, White Gold Dragon. As political struggles took hold of mainland China, Hong Kong became a place where cinema could develop freely.

The Shaw brothers, who later founded their own studio in 1958, would come to have a lasting impact on Hong Kong cinema.

Who were the powerhouses back in the day?

The post-war growth of Hong Kong was driven by an influx of people fleeing the war-torn mainland. In 1940, Hong Kong’s population stood at around 1 million people. By 1967, that figure had risen to 3.9 million.

But something else also defined those decades: with as many as 200 films produced a year, the late 40s, 50s and 60s were also the years when Cantonese cinema began to flourish, after a period of stagnation during the Japanese occupation.

This mainland brain drain brought with it an increase in talent, money, and ideas, but also engendered a divide between Mandarin and Cantonese media. Against the backdrop of the growing popularity of Mandarin film, Cantonese operatic films and low-budget martial arts films prospered.

Hong Kong localism, and nostalgia, behind revival of interest in Canto-pop

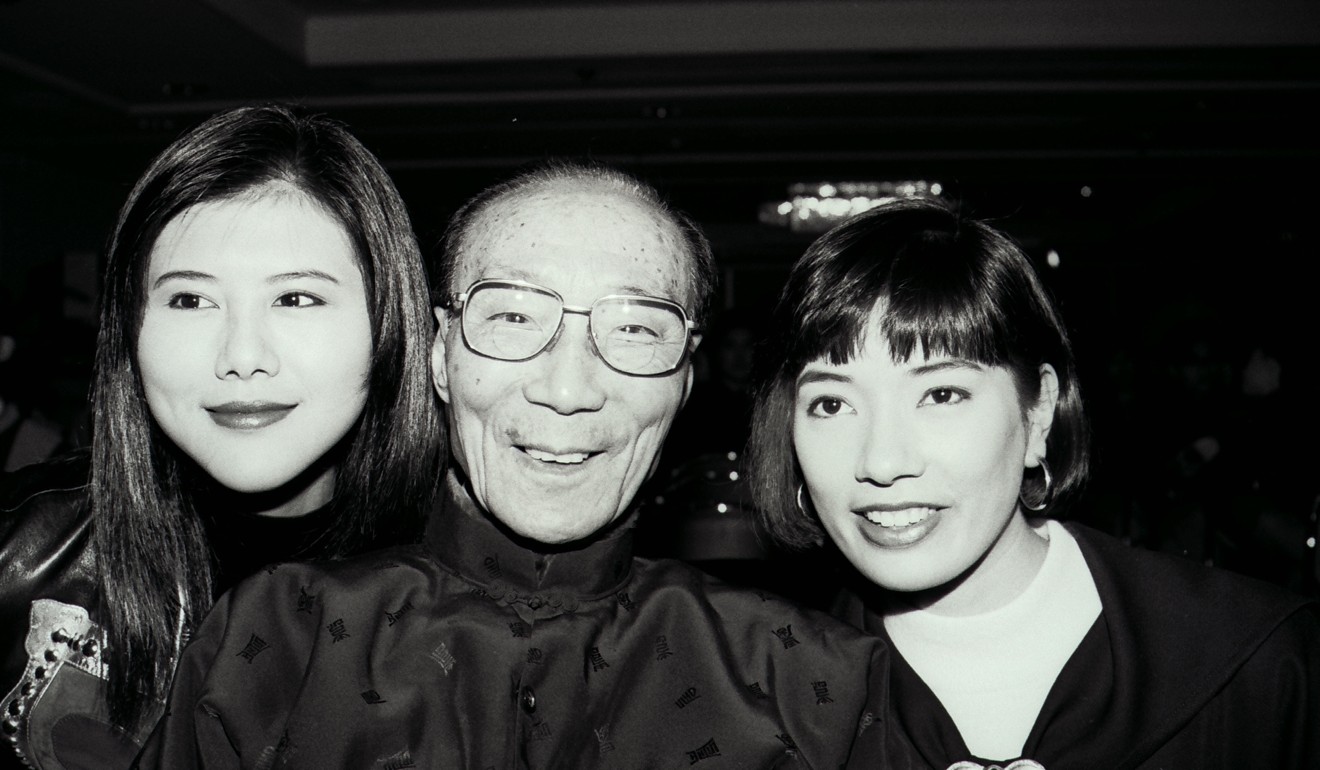

In the world of Mandarin-language films, a rivalry developed between the Shaw Brothers and Motion Picture and General Investments Limited (MP&GI) – the two industry giants of the day. The Shaws were known for their romantic melodramas, historical costume epics, and they reinvented wuxia martial arts films, while MP&GI specialised in Hollywood-inspired musicals, such as Mambo Girls (1957) and The Wild, Wild Rose (1960).

Ultimately, the Shaw brothers prevailed – the death of MP&GI founder and head Loke Wan Tho in 1964 sealed their competitors’ fate.

What was the era where local stars started to shine?

While Mandarin films began the 70s with the upper hand, Cantonese cinema made its comeback by the decade’s end, bringing realistic films about ordinary Hong Kong people to the big screen.

As Hong Kong’s middle class grew and the city that was once a fishing village became increasingly commercial and corporate, the industry moved its focus back to local audiences with resounding success. Films about the modern reality of Hongkongers were the taste of the decade, and Mandarin took a back seat.

The Shaw brothers saw continued international acclaim as kung fu movies exploded in popularity. In fact, the company produced the only Cantonese film of 1973, House of 72 Tenants, which quickly became a sensational hit.

With no kings or queens, can Canto-pop find its star again?

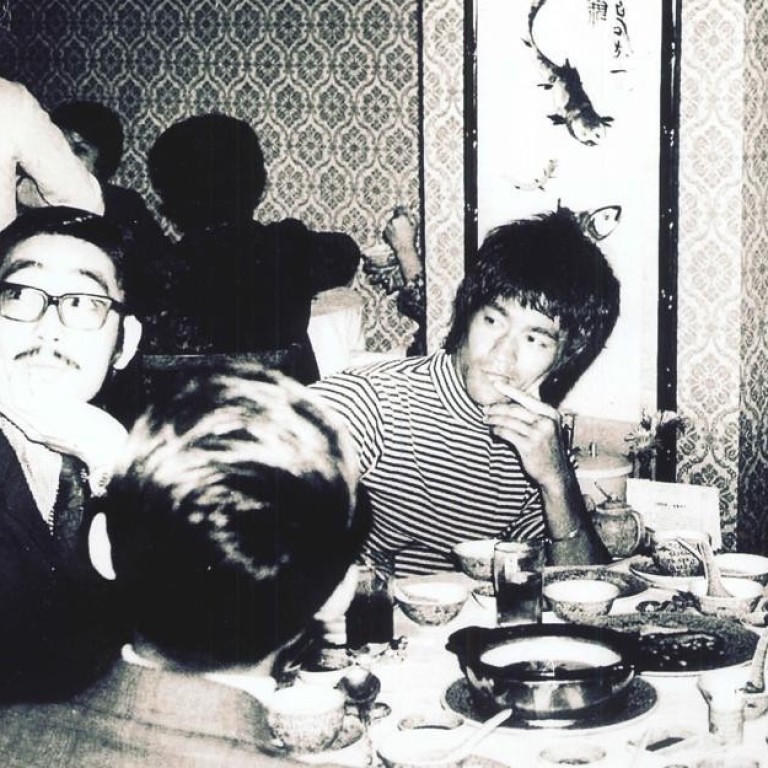

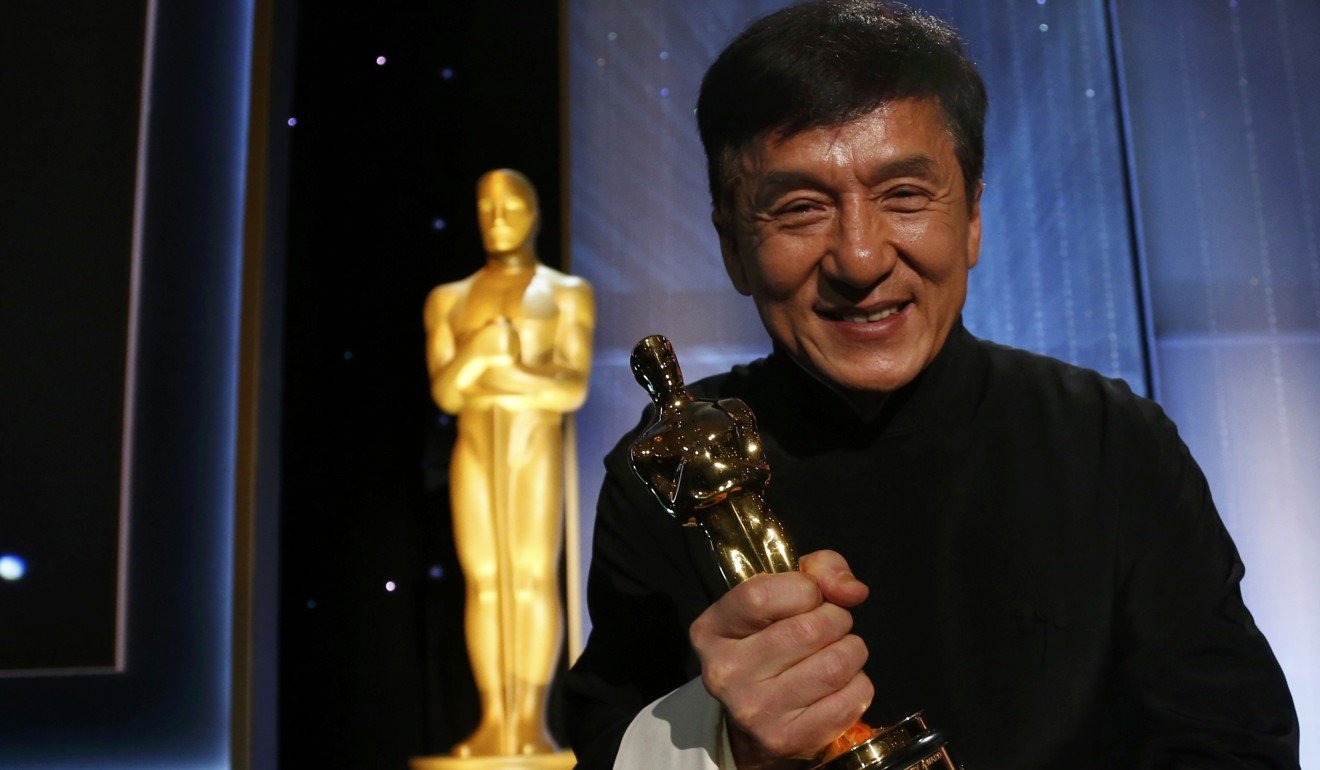

In 1970, Raymond Chow Man-wai and Leonard Ho Koon-cheong left Shaw Brothers and formed their own production studio, Golden Harvest. The new production company quickly gained traction by signing the rising stars of the time, including Bruce Lee, the Hui brothers, and later, Jackie Chan.

As a marriage of Cantonese television and cinema gradually began to revive the local flavour, the Hui brothers, who first became famous through TVB, broke records with their 1974 film Games Gamblers Play. The movie made US$1.4 million at the local box office and became the highest-grossing film at the time – marking a turning point in Hong Kong’s cinematic history.

When did Hong Kong cinema truly blossom?

As the new decade dawned, so did a new era for modern Cantonese-language films.

As Hong Kong exerted a dominance in its region akin to that of Hollywood, Cantonese films filled theatres across East and Southeast Asia, with Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan and South Korea, becoming important export destinations. The growth of Chinatowns and the cult popularity of kung fu films helped spread Cantonese movies into Western cinemas.

Director-producers Wong Jing and Tsui Hark led the Hong Kong New Wave movement; Wong with fan-favourite pulp films, and Hark with technical experimentation. Production company Cinema City, founded in 1980 by comedians Dean Shek, Raymond Wong and Karl Maka, paved the way with what became known as the “Cinema City style” of comedy-action. Triad films by John Woo and Alan Tang, traditional and stunt-driven martial arts fantasies starring Jet Li and Jackie Chan, and romantic melodramas featuring Brigitte Lin and Cherie Chung also won hearts citywide.

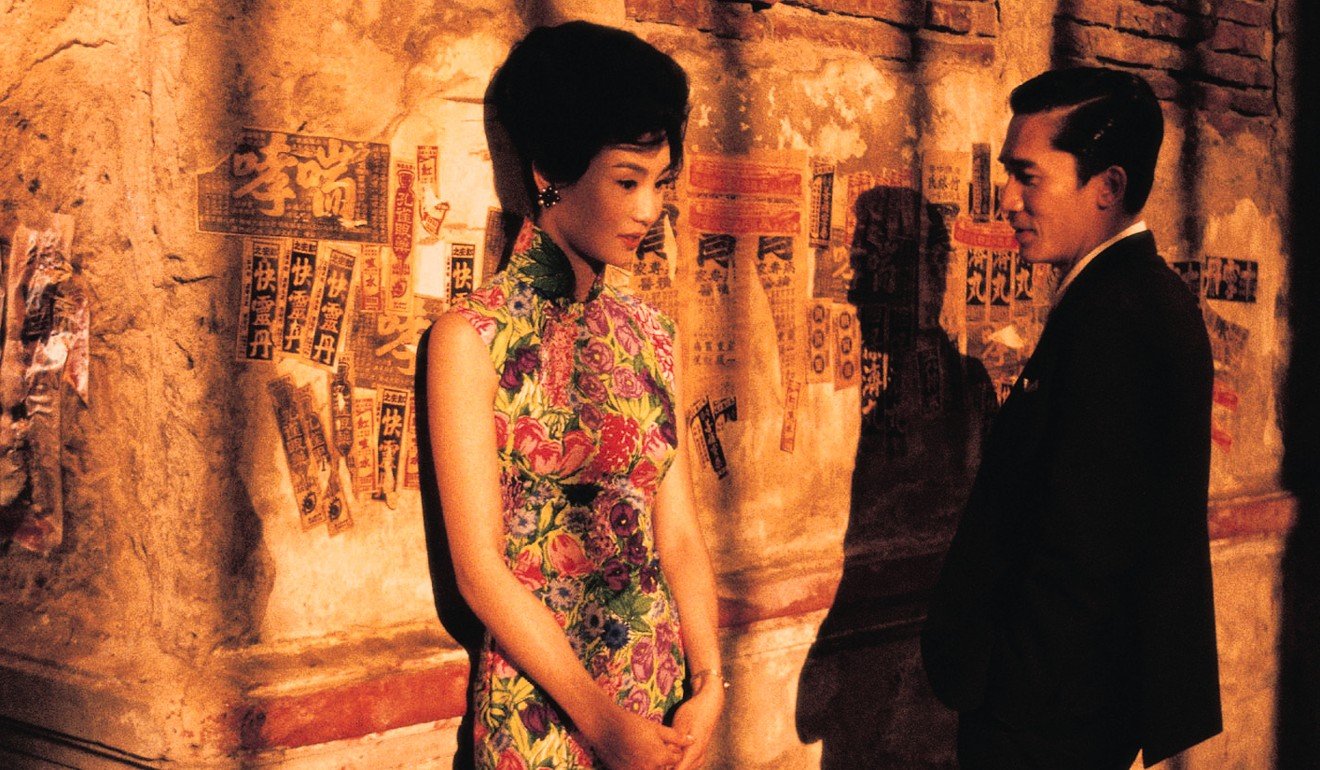

Against this backdrop, alternative art cinema by Ann Hui and Yim Ho, and later by “Second Wave” directors such as Stanley Kwan and Clara Law blossomed in popularity. Amid this, Wong Kar-wai began his journey towards international acclaim with his films in the late 80s and early 90s starring Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk and Tony Leung Chiu-wai.

Hong Kong film industry gets major breakthrough with mainland China deal

Why did the sun set on the industry?

In the early 1990s, Hong Kong cinema was running on a high: producing 400 films a year at its peak. But by the turn of the century, the number of films produced each year had dropped to just around 100. For the first time in decades, blockbusters imported from the US began to top box office ticket sales.

There were 121,8000 seats and 119 theatres across the city in the early 90s. But by 2017, Hong Kong had only 48 cinemas and 36,500 seats … So what happened?

A lot has been said about why this drop occurred. Some blame a drop in quality caused by overproduction, others point to a change in entertainment preferences. Others cite the brain drain of talent to mainland China’s new-found money.

Economically, the Asian financial crisis in the late 90s affected sources of funding and reduced the spending power of local audiences. As the city recovered, the increasingly wealthy Hong Kong middle class was seen to favour international films over the local. According to the Hong Kong Box Office, only 53 local films were released in the city’s 55 cinemas in 2018, while 300 foreign movies hit the big screen.

In fact, Little Big Master was the only locally produced film to make the top 10 box-office list in 2015 – coming in 10th behind nine foreign films.

Everything changed in Hong Kong after 1997, actor Anthony Wong laments

This decline has not gone ignored. In 2003, as the Sars outbreak swept up the city, halting cinema production and leaving cinemas virtually unattended, Hong Kong’s government implemented a Film Guarantee Fund in hopes of incentivising local investment in the movie industry. The government also created the Film Development Council in 2007, and later formed Creative HK to facilitate the development of local industries. These initiatives have seen little success.

The decline of Hong Kong’s film industry has corresponded with the rise of its counterpart on the mainland. As the lines between both sides continue to blur, co-production has become the flavour of the season. In 2016, over half of the movies created locally were co-productions with mainland China.

However, though Hong Kong has lost its title as the “Hollywood of the East”, the city remains one of the world’s largest movie exporters. Economically, this means that creative and cultural industries in Hong Kong – film included – make up 5 per cent of the city’s GDP. Only time will tell if this points to hope for Hong Kong’s cinema industry.