Hong Kong’s first Tiananmen vigil after national security law: residents weigh police ban and seek ‘other ways’ to mark June 4 crackdown

- Some plan to avoid Victoria Park, but say they will light candles at home or elsewhere in city

- Fate of alliance behind annual candlelight vigil in the balance, with some leaders behind bars

Hongkonger Mary Cheung* was 29 and visiting Beijing for the first time when she stopped at Tiananmen Square and snapped photographs cheerfully in April 1989.

Not long after she returned home from her holiday, mainland Chinese students began gathering in the square to protest against corruption and demand greater political freedom.

With memories of her holiday still fresh in her mind, Cheung could not believe the scenes of the bloody military operation that played on television screens and in newspaper images.

“How could the authorities do this to their people? They were young people with a great future ahead of them,” said Cheung, now 61 and a retired social worker. “They should not be forgotten.”

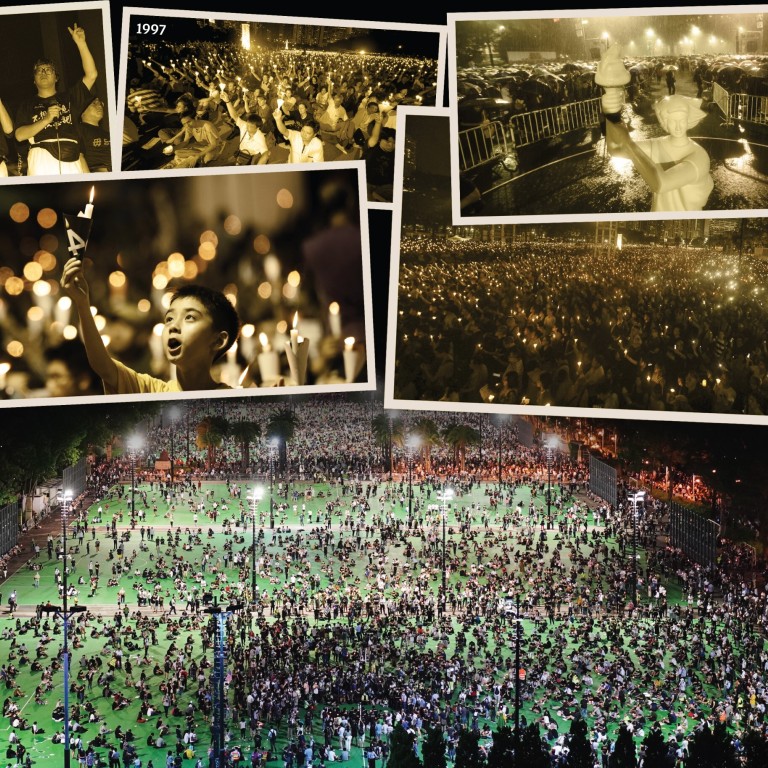

On the anniversary every year, tens of thousands of people – often many more – have made their way to the park in Causeway Bay, to hold flickering candles, mourn and offer blessings to the families of those who died or went missing that day in 1989.

But the scene of candles lighting up Victoria Park may already be a thing of the past.

What the Tiananmen Square crackdown on June 4, 1989 was about

The fate of the vigil organiser, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, is currently in the balance, with critics suggesting that even its aims might be against the law.

While there are Hongkongers like Cheung who remain determined to head to Victoria Park again on June 4, others say they will stay away and light candles at home or elsewhere in the city.

Time to play it safe, or press on?

It has always espoused five “operational aims” – the release of dissidents on the mainland; vindication of the 1989 pro-democracy movement; accountability for the crackdown; the end to one-party dictatorship in China; and building a democratic country.

These aims have sparked questions as to whether the group could be in breach of the national security law.

It’s crystal clear that it’ll be risky to enter Victoria Park this year. I won’t stop anyone from doing so, but will only remind them to weigh the benefits and costs

In an interview with the Post before a court in May ordered he be held in remand over another unauthorised assembly, alliance vice-chairman Ho acknowledged the risk of marking June 4 at Victoria Park this year in defiance of the police ban.

He admitted that even within the alliance, views were split between those who believed it was best to play it safe and guarantee the group’s survival, and those who wished to cede no ground.

“It’s crystal clear that it’ll be risky to enter Victoria Park this year. I won’t stop anyone from doing so, but will only remind them to weigh the benefits and costs,” said Ho, a lawyer. He added, however, that the societal impact of being sent to jail was diminishing, as so many activists were already behind bars.

Hong Kong teachers drop annual ritual of telling students about Beijing crackdown, fearing ‘red lines’

Although fully aware of the need to protect the alliance, he said he also believed it should not surrender its basic principles.

“Our narrative is clear. [The alliance] is an advocate for peaceful and orderly constitutional reform. We are not advocating violence. We are just trying to persuade the Chinese Communist Party,” he added.

He suggested that instead of going to Victoria Park, Hongkongers could be “flexible” as they marked the Tiananmen crackdown this year. The government could not ban citizens from lighting candles at home or turning on their mobile phone lights on the street, he said.

“We can regard the whole of Hong Kong as Victoria Park and spread out our candlelights, or enter the park at different times and post pictures on a ‘protest wall’ online,” he added.

The alliance will not organise the vigil this year, and Tsoi will not be going to Victoria Park.

“But we believe that Hongkongers will use their own ways, at different locations, to commemorate June 4,” he said.

Officials accused of using Covid-19 as excuse to ban Hong Kong’s Tiananmen vigil

His alliance colleagues Ho and Lee Cheuk-yan were sentenced to 18 months’ jail each over the same protest. Lee was already behind bars for his role in other unauthorised protests in 2019.

‘Risky to go to Victoria Park’

In a Chinese newspaper column published on Monday, mainland scholar Tian Feilong, director of the semi-official Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies in Beijing, doubled down on his accusations that the alliance was running afoul of the national security law with its “subversive” goal of ending “one-party dictatorship”.

He urged the Security Bureau to take action, either by demanding the alliance remove its “subversive” goals, or outlawing the group outright – as was done to the now illegal Hong Kong National Party – if it refused to comply.

Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of the same think tank, was convinced the alliance’s days were numbered.

“The central government sees the June 4 issue in Hong Kong as a national security issue,” he said. “From the outset, the alliance was set up to be anti-Communist Party. It also has links with anti-China elements and dissidents outside Hong Kong.”

However, he believed the Hong Kong government would not take on the alliance without first reaching a consensus with Beijing on the steps to take.

Hong Kong organisers of Tiananmen Square vigil lose appeal over ban

With the Communist Party celebrating its 100th anniversary on July 1, Lau added that Beijing might not want to take any chances and have anti-China forces stirring trouble.

The alliance was a patriotic group in the sense that it recognised one China, Cheung said. Those who believed the group endangered national security just because it did not agree with the Communist Party did not have their finger on the public pulse, he said.

Dissidents ‘sad for Hong Kong’

Exiled Chinese writer and filmmaker Su Xiaokang, an active member of the 1989 student movement, was heartbroken the day the tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square.

He said he was now equally sad about the way politics had played out in Hong Kong.

“Hongkongers have given their all but still failed to reverse the fate of falling under the Chinese Communist Party’s dictatorship,” said the 72-year-old, who now lives in the United States with his wife and son.

“I am extremely sad and heartbroken. The grief is on par with what I felt some 30 years ago when the Tiananmen Square protests were finally crushed by tanks.”

06:13

Thousands of Hongkongers defy ban and gather to mark Tiananmen anniversary

Su wrote the script for River Elegy, a thought-provoking, controversial documentary series telecast on the mainland in 1988 that was said to have inspired young people to join the student-led protests in Beijing.

Following the 1989 crackdown, he found himself on China’s list of seven most wanted intellectuals.

Even if the Victoria Park vigil ended up banned, Su expressed confidence that Hongkongers would persist and find ways to remember the crackdown by different means.

“Passing on the memory of June 4 is supposed to be the responsibility of my generation of intellectuals. We are duty-bound to carry on, to commemorate it every year all around the world,” he said.

‘Grandma Wong’ arrested over Tiananmen march following police ban of June 4 events

He said that 32 years after the crackdown, the incident had not yet been exposed fully on the mainland. “Truth has not been revealed, justice has not been served, and there will not be light in China,” Yan said.

For some, it’s so hard to decide

Retiree Matthew Lee*, 75, has been a volunteer at the Victoria Park vigil every year from the start, mostly as a marshal.

“There was a year when I was touched to see so many people braving the pouring rain and insisting on staying there,” he said.

He was there last year too, despite the police ban. But this year, with the national security law in place, he had not yet decided whether to go.

“I may use my own way to remember,” he said, adding that he might just light a candle at home.

Hong Kong organisers of Tiananmen Square vigil lose appeal over ban

Catherine Cheng*, a 33-year-old worker in a public organisation, has attended almost every vigil since 2009 and was at Victoria Park last year too.

She knew nothing about the 1989 crackdown in Beijing until she went to university. Her high school teachers had never talked about it.

She remembered being overwhelmed, the first time she stood in the sea of people holding lit candles in 2009. She had never taken part in a rally before that.

“The vigil in Hong Kong is the only large-scale one in the world. It’s an important event for the dead, their family members, and those who are still oppressed in mainland China. It sends encouragement to them,” she said.

Organiser of Tiananmen vigil opens museum to visitors wishing to leave flowers to mark anniversary

A few years ago, the rise of localism in Hong Kong prompted some young people to abandon the vigil, saying Hongkongers ought to care more about what was happening in their own city. Some disagreed with the alliance’s goal of building a democratic China, suggesting they did not care about what happened on the mainland or its future.

Cheng said: “At the vigil last year, I felt that Hongkongers had put aside this dispute.”

This year, she feared the possibility of being arrested and, as of the weekend, had not decided whether to head to Victoria Park again.

But retired social worker Mary Cheung is not about to end her annual ritual of more than three decades. She insists she has no intention of flouting the national security law.

“As a citizen, I have the right to go to Victoria Park,” she said. “I am not going with many friends and will not violate social-distancing rules. What grounds will they have to arrest me?

“The people who sacrificed their lives for the pursuit of democracy need us to remember them.”

*Names of interviewees changed at their request.