Hong Kong-led team develops blood test that can catch dementia in early stages, with nearly 90% accuracy

- Previously identifying patients suffering from early stages of condition was difficult, as doctors had to rely on clinical assessment, university team says

- Early identification can allow for treatment options that would be otherwise unavailable if condition had progressed, according to researchers

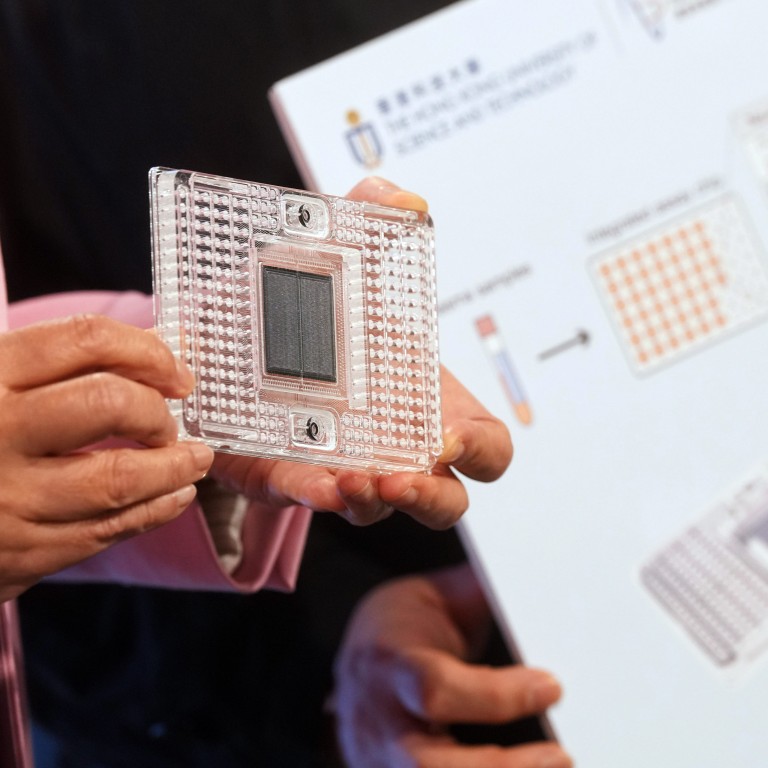

An international team led by Hong Kong researchers has developed a blood test it claims can identify the early stages of dementia with an accuracy rate of nearly 90 per cent, allowing for treatment before the onset of symptoms of the neurodegenerative condition.

The test was being offered by a private company at a cost of about HK$7,000 (US$895), and discussions were under way over making it available in the public health sector, researchers from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, which led the team, said on Monday.

“If an early diagnosis can be made, the heavy burden brought by the disease on families and the communities can be greatly alleviated,” team head and university president Professor Nancy Ip Yuk-yu said. “Early stage patients can have effective management and treatment in a timely manner.”

The research team previously developed a blood test that could identify Alzheimer’s disease, with a claimed accuracy rate of more than 96 per cent, but the latest version of the screening can discover the condition in its early stages.

The latest test has an accuracy rate of more than 87 per cent, according to the team.

Ip said that in the past it was difficult to identify patients suffering from the early stages of the condition, as doctors had to rely on a clinical assessment, which could be subjective.

Patients were usually aware of the need to see doctors only when they had developed symptoms, but that was the time when the disease had advanced to a stage too late for effective treatment, she said.

“An easy, precise and minimally invasive blood test can provide a feasible solution for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease around the world,” Ip said.

Hong Kong team develops faster way to screen for Alzheimer’s disease using AI

The test looks at 21 protein biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s to determine whether one is suffering from the condition. The levels of different proteins can show the seriousness of the disease.

It had also been tested on both Chinese and European people in past studies, showing consistently high accuracy in early detection of the disease across different ethnic groups.

The team hoped the test could help facilitate the use of a drug that targets the early stages of Alzheimer’s and which the United States Food and Drug Administration approved for use last year.

“The test can help screen, diagnose and determine which stage of condition a patient is in and help decide on a treatment plan,” said Jason Jiang Yuanbing, a postdoctoral fellow from the university’s division of life science and member of the research team. “It can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of medication and treatment progress.”

Fanny Ip Chui-fun, chief scientific officer of the Hong Kong Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases, a research facility at the Hong Kong Science Park affiliated with the university, said the test had been licensed to Cognitact. The start-up is a spin-off of the university.

Hong Kong scholar gets mainland Chinese support for Alzheimer’s research effort

But the team could not reveal how many people in Hong Kong had taken the test, saying it was company information.

Fanny Ip said the test would be suitable for people who had a family history of dementia and had not yet been seen by a doctor, or those 55 or older who showed signs of memory loss.

She said the team was discussing with authorities the possibility of including the test in regular screening offered by the public health system.

A spokesman for the Department of Health said its elderly health centres provided assessment and examination for dementia using tools that were internationally recognised and suitable for local elderly people.