Art for more than art’s sake

- Students looking to work in the art world need to equip themselves with knowledge of business, technology and social issues

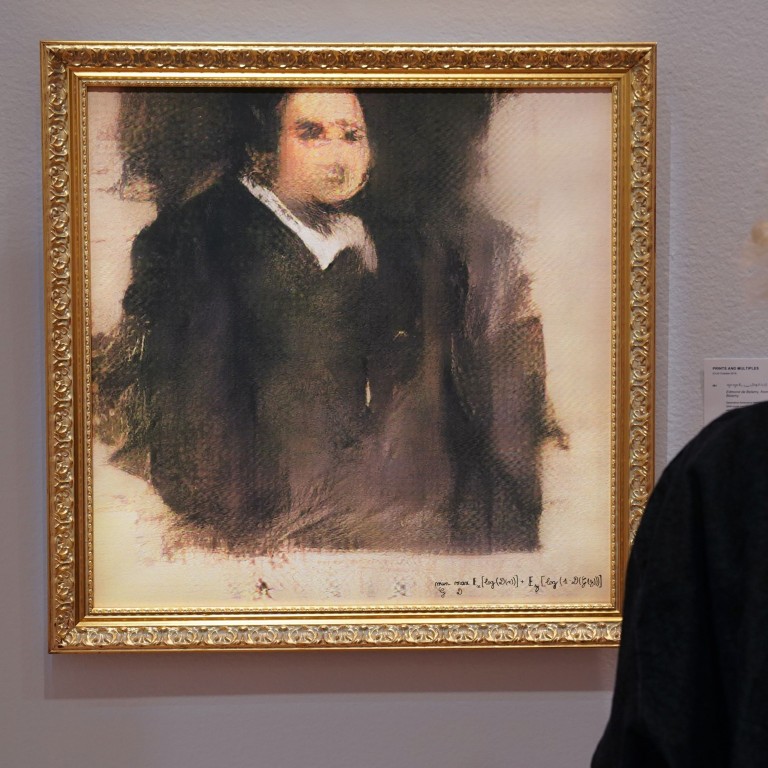

It caused something more than a stir when the first artificial intelligence (AI)-generated artwork – an indistinct face of a pseudonymous Edmond de Belamy – sold for US$432,500 on an October evening in the auction house of Christie’s New York. It marked a significant milestone for new thinking about the possibilities of technology in the art world, according to Jane Hay, international managing director of Christie’s Education.

“AI has already been incorporated as a tool by contemporary artists and as this technology further develops, we are excited to participate in these continued conversations,” Hay says. While the collective of artists and AI researchers at Parisbased collective Obvious “painted” the portrait with an algorithm, the art world is moving at a rate faster than Monet’s brushstrokes.

To adapt to these changes, Christie’s Education recently launched a new master’s programme in art history and art world practice, starting classes next September. Steeped in its 40 years of history, Christie’s Education is the only academic institution wholly owned by an auction house.

The 15-month taught postgraduate programme in London offers participants an insight into the history and current practices of cataloguing and curating art, as well as theories and the art market. Students will be able to develop an understanding of the historical context of different works of art, as well as acquire the curatorial skills for careers in museums and galleries, not to mention, art festivals that are cropping up across the globe.

“The object-based character of the new MA complements the existing MSc (art, law and business)’s legal and commercial emphasis,” Hay says.

It is topped off with a work placement component, which opens up opportunities in positions in the UK and abroad for up to 12 weeks, granting students entry into the art world, especially its tight-knit professional network, which could otherwise be an intimidating walk for newbies.

“The art world is a fascinating area but at the same time can be immensely complex given its plethora of players and new platforms,” says Sara Mao, a 2008 graduate of the master of letters programme in history of art and connoisseurship, from Christie’s Education and the University of Glasgow. She joined Christie’s as junior specialist trainee in the same year and is now the director of Christie’s Education in Asia.

“I gained a much deeper appreciation for history, the cultural fabric of China, and the development of artists and artworks in a very relatable context,” says Mao, who chose to specialise in Chinese modern paintings.

Now head of sale of Chinese Modern Paintings at Christie’s Hong Kong, she is responsible for curating programmes around Asia from Chinese Art to Western Art, paintings to sculptures and installations.

According to Hay, 94 per cent of the 2016-2017 batch of Christie’s Education students found employment within six months of completing their studies, of which around 100-150 are employed in the Christie’s group. “This includes our global president and lead auctioneer, Jussi Pylkkänen,” she says.

Online courses have also become a relevant way of offering art lovers and career changers everywhere business insights that can be absorbed at their convenience. Christie’s fourth online course, art market economics, will be launched in January, presented by leading art market economist Dr Clare McAndrew.

Versatility is indeed an important element when it comes to continuing education, a mobility which grants students access to different areas of the industry. This is what HKU SPACE has achieved by partnering up with leading arts and design college Central Saint Martins (CSM), of the University of the Arts London, for an MA programme in arts and cultural enterprise.

“The programme has been developed specifically in response to the need for multi-skilled individuals who can both generate ideas for original arts and cultural events, and provide leadership for the teams that realise them,” says Dr Olive Cheung, a HKU SPACE college lecturer, adding that it would equip students with the skills needed to become creators in arts management and cultural production.

The two-cohort course, one in London and another in Hong Kong, is designed to help students expand their collegiate network and ensure the worldwide reputation and relevance of their degree. According to testimonials from alumni, the course content delivered in both cities are exactly the same.

The course features a combination of face-to-face classes delivered by CSM faculty members and HKU SPACE staff and online teaching where students engage with tutor-led live seminars, discussion groups and webinars. Cheung says the programme caters to experienced graduates who wish to challenge themselves by developing innovative approaches to arts management and cultural production.

“These individuals will [become] dynamic, responsive, fluent in both the public and private sectors, and have the ability to collaborate and develop networks,” he says. Upon satisfactory completion of all seven modules – researching arts and cultural enterprise, practice, policy and markets, contexts (local and global challenges), arts entrepreneurship, business models and finance, focus: social impact and innovation, dissertation or live project – students will be awarded the master of arts in arts and cultural enterprise from CSM.

Elaine Ho, a graduate of the two-year programme, recalls having a class full of leaders from all sectors, ranging from art entrepreneurs and teachers to senior management of local media and music industry.

Her final year project, for which she organised a visual art fun day in a shopping mall, yielded feedback from the mall owner that far exceeded her expectations. “The cultural theories we learnt turned out to be very useful when applied to the local commercial sector,” she says.

For those looking to become art practitioners in Hong Kong, Baptist University’s master of arts in visual arts programme is an excellent choice.

Professor Louis Nixon had been working as head of the school of fine art at Kingston School of Art before taking the helm as the director of the university’s Academy of Visual Arts earlier this year. Describing the British art curricula as largely ideas-based, he says these concepts could manifest themselves in unrestrictive forms, whether paintings, sculptures, films or stills – which explains why he was struck by the greater emphasis on acquiring traditional skills at art institutions in Shanghai and Beijing. Coming to Hong Kong.

However, he saw a unique beam shining on its art education landscape.

“I would say that the colonial and post-colonial governments have left a quite confusing state where Western and traditional Chinese art meet somewhere,” he says.

The school’s master programme brings together the best of both worlds, or in fact, the best of every facet of the world.

“Although many think that art is just work in a studio by oneself, oftentimes nowadays we [think of] art as an ecology of people in different disciplines working together. It’s never one person’s job,” says Kingsley Ng Siu-king, assistant professor at the academy.

Adopting a cross-sectional teaching approach, the programme aims to familiarise students with different artistic practices across the globe, as well as professional knowledge and cross-cultural awareness in a diverse terrain of artistic talents.

A typical study plan will consist of a core set of courses which teach students the essential knowledge and skills to perfect their field of practice, plus a concentration-focused curriculum where students are given tutorial supervision to explore their own creative path of interest. They can pick from two concentrations – “Studio & Media Arts” or “Craft & Design”.

According to Nixon, the academy has been investing substantial resources in the creative media practice research cluster that would unite the departments of visual arts, film, creative writing and music, to create a platform to produce projects in a collaborative manner. “The focus is to help Hong Kong develop the confidence to become a city of creativity and culture, which it hasn’t always been seen as,” he says.

The Zurich exchange programme, for instance, invites students from various creative disciplines – from Zurich University of the Arts and Baptist University – including dance, theatre, visual arts, music, design and architecture to co-produce artistic projects and installations. Students learn from one another across fields in a stimulating process that can, as Nixon puts it, “fill the gaps”.

As both professors are hasty to point out, there has been, in the art education in Hong Kong, a tendency to overlook local artists. The academy is therefore setting up an exhibition platform where five successful local artists will select five emerging counterparts for a joint exhibition in March next year.

Social engagement programmes, a highlight of the MA programme, are another way to make these aspiring artists visible to the public. Local artist and professor at Baptist University, Leung Mee-ping, fondly known as Momo, established the Play Depot project at the Cattle Depot Artist Village in To Kwa Wan in 2017, where artists work with children to upcycle waste materials to toys, as a means of transferring creative knowledge through co-creation.

“While a lot of the art is [branded] with a capital ‘A’, where it’s defined by institutions or people who have a lot of expertise or power to dictate what is art – that I think we would always respect – there’s also the art with the small ‘a’, the art of the everyday,” Ng, himself an interdisciplinary artist with a focus on conceptual, site-specific, and process-based works, says,

“We can learn that art in the communities and activities can be more ‘grassroots’ from the bottom up.”