The hidden racism plaguing Hong Kong, and how one student is fighting back

Lamia Sreya Rahman is overcoming difficulties with Cantonese and discrimination to help fellow ethnic minority Hongkongers find success

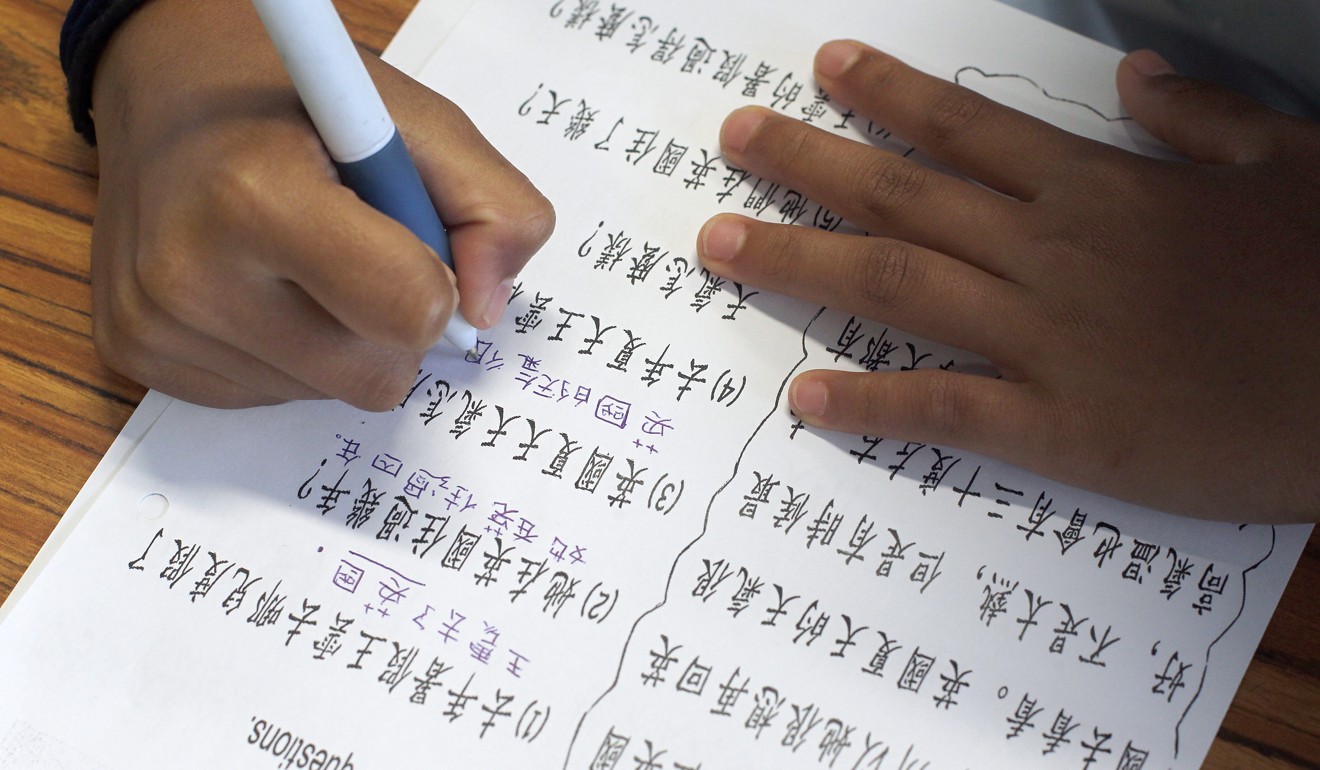

Hong Kong-raised Lamia Sreya Rahman is not yet fluent in Cantonese despite having studied the local dialect for more than a decade.

It’s not because she is lazy or anything to do with her Bangladeshi ancestry. Rather, it’s because what she was taught in school was too simple, according to the 20-year-old. It allowed her to strike up only rudimentary conversations with residents of the city of seven million.

“The content taught in school is frankly too easy and repetitive,” Rahman said at a recent panel discussion at the Hong Kong legislature. “I have been studying Cantonese for 15 years, and I am only able to say: ‘I want to go to the bathroom’, and ‘I want to eat fishballs’.”

Chinese is taught as a second language to ethnic minority pupils in Hong Kong schools. They are allowed to take an easier public examination in the language to secure a place in tertiary education – a policy critics describe as a band-aid remedy for their difficulties integrating with mainstream society. The language, experts say, is the key to social integration and mobility.

Rahman, in her third year of an American studies and criminology course at the University of Hong Kong, said her less than satisfactory Cantonese skills had hindered her integration into society and possibly her future career.

“What the government overlooks is the fact that we might be the future of Hong Kong,” Rahman said while studying with a friend at a coffee shop in Mei Foo recently. “And even if the government has started to recognise the problem, its solutions are still rather short term.”

Chinese-language help for Hong Kong’s ethnic minority pupils lacks transparency, NGO finds

She said many of her friends from a similar background were looking for other ways to learn Cantonese rather than relying on being exempt from learning the language to an advanced level.

“I don’t know any place better than I know Hong Kong,” Rahman said. “I am ethically Bangladeshi, but I know much less about Bangladesh than I do about Hong Kong.

“If Cantonese is supposed to be part of my identity, and I am not given a chance to learn it properly, does it make me any less of a Hongkonger?”

Rahman said what prompted her to speak up at the Legislative Council was her many experiences of racism. Ethnic minorities, many of South Asian origin, make up 8 per cent of Hong Kong’s population.

Rahman first became an advocate for her peers following an unhappy incident last year as a part-time English-language teacher at a local secondary school.

Her Form Four and Five pupils used a derogatory Cantonese term, usually used to describe female Filipino domestic workers, to describe Rahman behind her back.

In Hong Kong’s battle over language, ethnic minority children should get to learn Chinese in Mandarin, rather than Cantonese

“One day, a colleague of mine sent me a screenshot of an online discussion forum in which the students were saying: ‘Why is a bun mui teaching us English?’ And I was like, what? But I had such a good relationship with them,” Rahman recalls. “I was thinking, maybe people don’t accept me exactly the way I perceive them to.”

She lamented that her teaching ability had been completely overshadowed by her ethnic roots. She never received an apology from either the pupils or school officials, and later quit the job.

“I know a lot of my friends have been humiliated on public transport,” Rahman said. “There’s a reason why we all study at ethnic minority schools and why we can’t get access to local education.

“All these minor incidents sort of pushed me to do a lot of advocacy work.”

Rahman, who is also the president of the Equal Opportunities Student Ambassador Club at the University of Hong Kong, said her parents were supportive of her advocacy.

She said: “After I was admitted to university, my mum and dad told me: ‘There are many ethnic minority kids who are trying to do the same as you, but failed. So why don’t you take this opportunity during your four years at university to create a pathway to justice for them?’”