Embracing the differences: how a local school develops a curriculum that truly caters for all

Inclusive education means adopting a differentiating approach at the Hong Kong Red Swastika Society Tai Po Secondary School

These days, there is plenty of talk about inclusive education, but Hong Kong Red Swastika Society (HKRSS) Tai Po Secondary School is truly committed to the principle.

The Chinese-medium school began to implement differentiated teaching and learning practices back in 2006. And, since then, a dedicated team of teachers has developed a comprehensive curriculum plus the teaching materials and assessment tools to empower students of various abilities and educational needs to learn effectively at a pace which suits them.

According to the school’s vice principal Franky Poon, the school is committed to providing as many choices as it can, so that no students feel excluded in their journey to greater learning and personal development.

“Being part of the public education system, we believe that schools should not turn students away because they don’t measure up in terms of the standard academic system,” Poon says. “That is simply wrong. School is a reflection of society. All of our students have a role to play, and they enrich each other’s learning experience and personal journey.”

At HKRSS Tai Po Secondary School, there are more than 100 students diagnosed with special learning needs ranging from autism and ADHD to dyslexia and speech delay. A few pupils have hearing or visual impairments. In addition, though, more than 20 students have qualified for the Hong Kong Academy of Gifted Education.

“This is the way a school should be,” says Poon, who was awarded the Chief Executive’s Commendation for Community Service in 2013 for his contribution to inclusive education. “If schools start rejecting and excluding students with different needs and aptitudes right from the beginning, what kind of message are we sending to our children?”

In order to achieve the goal of inclusive education, the school has spent significant time on curriculum development over the years.

The traditional syllabus was seen to be exam-oriented rather than student-centric. Therefore, the school set up a team of panel heads for Chinese, English, maths, liberal studies and science and divided the curriculum into three categories: core, extended and challenging.

The first contains the most factual and fundamental components for each subject. The second requires a deeper understanding, usually involving more analytical and cognitive skills. The third offers students the chance to explore beyond the curriculum, doing more in-depth investigations and following up specific interests.

This differentiated curriculum has corresponding learning goals, course content and assessments in line with each student’s respective category. All relevant information is uploaded to the school’s intranet so parents and students can understand the learning strategies and what’s behind them.

“It is a very fluid system where students can pace themselves in different subjects,” Poon says. “Some, for example, may be fast learners in maths but prefer to take the core level in English. We don’t label our students. We just give them the right kind of environment and the right set of tools to focus on their strengths and improve on their weaknesses.”

A constructive approach is also taken to homework and examinations. The school views them as tools for students to measure what they know and to make suitable progress.

So, in the design and content of homework assignments, the core level may come with prompts, visual aids and more straight-forward questions. For the other levels, the exercises may be more text-heavy and have more complex questions.

“We want the students to have a sense of achievement,” Poon says. “Many parents have seen their children’s pride when they can finish their own homework or complete an exam paper instead of leaving the page blank. This contributes to confidence in learning because our system doesn’t make children feel like failures. They know they can make progress and that their efforts will be recognised and celebrated.”

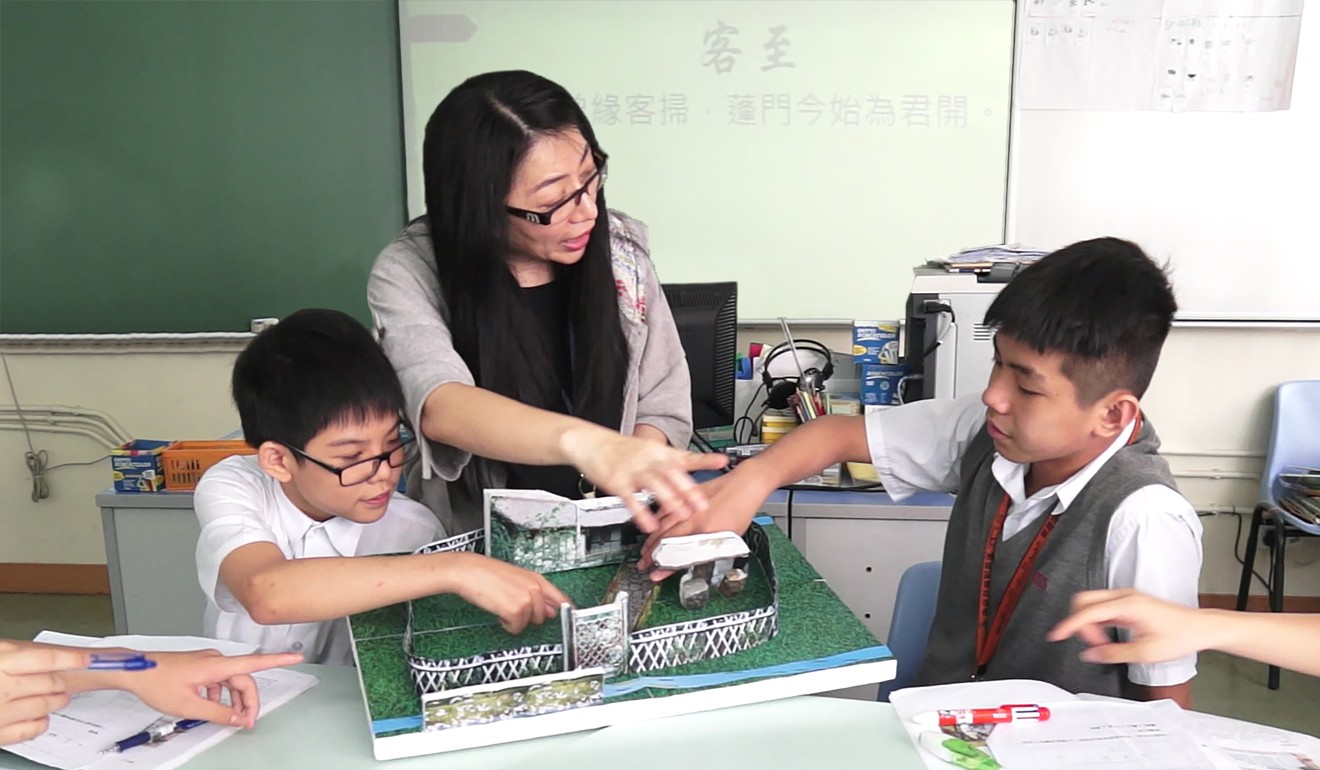

In the classroom, students are sometimes in groups based on ability, but it depends on the subject and lesson.

For example, a maths lesson might see all students in one form taking part in the same learning activity, with the classroom transformed into a marketplace. Some would play the role of customers, required to work out the total price of purchases and stay within a budget. Others doing the extended level in maths would be the cashiers. And those at the challenging level might act as auditors. This allows them to participate in the same activity, but to tackle different tasks and worksheets.

For Chinese, English and maths, all Form 1 classes take place at the same time, but around 10 students join a separate “resource class”. There, a subject teacher offers individualised learning support, so students can to return to the main class group by the time they move up to Form 2 and beyond.

The school is also implementing a mentorship programme which sees each teacher advising one or two mentees a year and keeping track of their personal development. The pairings are based as far as possible on shared interests and hobbies. The teacher might arrange a regular chat over a snack or lunch, or, perhaps, a game of basketball in the playground. Ideally, there is also closer contact with the respective parents.

“It is, indeed, a lot of work for all of us,” Poon says. “But our teachers feel immensely proud of being able to do something different from the mainstream system and against the odds. At the same time, though, we should not take their passion for granted.”

For that reason, the school aims to apply smart management practices to minimise unnecessary workload. As an example, all teaching materials, lesson plans and worksheets are now uploaded and made available via the intranet to avoid duplication or starting from scratch.

Over the past five years, Poon has seen more parents and teachers interested in the school’s inclusive ideals and practices.

While heartened by this, he also recognises the need for greater social equity in the broader public education system.

In particular, with the government subsidy for students with special education needs (SEN) capped at HK$1.5 million per year per school, there are clear financial obstacles for schools which want to take more SEN pupils.

‘In my opinion, inclusive education should be the norm, not the exception,” Poon says.

A Case Study

Miranda Tung’s son, who is now a Form 2 student at HKRSS Tai Po Secondary School, loves his English lessons. He tackles homework with real enthusiasm and proudly shows his mother how many points he has scored in classroom dictation exercises.

It is a far cry from when he was in primary school, where it was never like this.

“What made the difference is the way the school designs lessons, homework and exams according to how the students learn” Tung says.

Her son has been diagnosed with mild autism and ADHD (attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder). Living in the Ma On Shan catchment area, she opted to send him to HKRSS Tai Po Secondary School, with a two-hour daily commute, rather than accepting offer from other mainstream secondary schools.

Those schools, she felt, have a tendency to start pushing academic performance in the senior forms to boost their track record in public exams. That, though, could lead to marginalising students with different abilities.

Therefore, Tung chose a school where the education ideals and focus on individualised care are reflected in the curriculum design, teaching methods, the way things are run.

“The people here are so thoughtful and they truly seek to empower their students,” Tung says. “For example, traditionally, English dictation is a subject where marks are deducted for every mistake you make. But for them, points are given for every correct answer; how cool is that?”

Chan Wai-yee, who has taught maths and physical education at the school for 28 years, has a great sense of achievement from being part of the school. It has given her the chance to grow professionally and to understand the importance of an inclusive setting.

‘It is so touching to see my students grow in confidence when doing maths,” says Chan, who also teaches a resource class for Form 1 students. “Most of them used to be scared of the subject because the traditional system in primary school constantly failed them.”

Some parents have told her how their children used to be so reluctant to do homework because they were fed up being reminded time and again that they did not measure up.

“Now they are eager and able to finish their homework and, when they come to class, they will raise their hands and compete to answer the questions,” Chan says. “They feel capable of learning new skills. What more can a teacher ask for?”

Chan is also part of a mentorship programme and is still in touch with a mentee she met 10 years ago, giving advice on work and relationships.

She finds it a privilege to be able to recognise and appreciate the talents in each of her students and to make a positive change in their lives.

“It opens my eyes as an educator and a mother,” Chan says. “It might be easier to teach in a traditional setting, but then I would not have become sensitive to the many different needs children have and how they can all make the world a better, richer place.”