The only way is not up, says Hong Kong architect who thinks city should rethink its vertical growth

William Lim warns high-rise buildings add to problem of traffic congestion as more vehicles park on streets

Hong Kong architect William Lim Ooi-lee is surrounded by skyscrapers in the city’s business district, Central – a few of them designed by him.

But looking up, the 60-year-old says he believes that building vertically fast is not the best for the city’s urban development.

Lim, a registered architect in both Hong Kong and the United States, warns that high-rise buildings will add to the problem of traffic congestion as more vehicles will be parking on the streets or going in and out of these buildings.

“One of the side effects of a high-rise is it also increases traffic congestion,” Lim says. “We need tall buildings to solve the housing problems, but they need to be well-planned with good infrastructure and environmental strategies.”

Lim, who graduated from Cornell University with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture, worked in Boston as an architect for five years before returning to Hong Kong in 1987. Five years later, he founded architecture and design firm CL3, where he is now managing director.

Lim says he likes Hong Kong because it is the best mix of old and new. And as many of the city’s old districts have recently been renewed and replaced by high-rise buildings, the father of two sons says heritage is very important to Hong Kong and needs to be preserved. The Blue House Cluster in Wan Chai, according to Lim, is a good example of “great preservation effort”.

“Hong Kong has many old buildings in need of repair,” he says. “I don’t think the solution is necessary to be bulldozing them.”

What did people in Hong Kong think about architecture in the 1980s? And how is it different from now?

Architects then were expected to do a lot of administrative work, such as submitting building plans to the government and making sure they were approved. Design usually came second. A majority of architecture firms in Hong Kong were more focused on how to cope with local building regulations, rather than how pretty the building looked. Local architects were familiar with the local building regulations and that was all most employers cared about. Those educated overseas were more focused on the design of a building. I think fewer than five large firms at that time had some sort of department for architects who came from overseas and focused on design.

I think, traditionally, people did not agree that building something was an art form. Back then, many expected architects to serve the people. It wasn’t until 20 years ago, people started to recognise the importance of architectural design. The rise of the HSBC Building and Bank of China Tower had shocked the local architectural industry and since those two buildings, more overseas architects were invited to design buildings in Hong Kong.

From an architect’s perspective, why do you think the HSBC Building and the Bank of China Tower are so special?

The HSBC Building was designed by renowned British architect Norman Foster and it was the most expensive building in the world at the time. The tower was built by assembling different components from overseas, an approach that was very advanced and different from Hong Kong tradition in the 1980s, where most of the buildings were made of cement and concrete.

The Bank of China Tower, which was designed by IM Pei, was special because it was once the tallest building in Hong Kong. It showed that a building should not only be defined by its function but the designer’s architectural thinking. Some people at that time thought the building did not have good feng shui because of its triangular angles. I think many Chinese people dislike triangular angles, but that is why the tower was so special and was considered to be a breakthrough in the society in the 1980s.

How do you think the design of a building could represent a city or a country’s identity?

Lots of cities did not appear on the map until they had some iconic buildings. I think the design of a building is extremely important to a place. For example, not many people were aware of Bilbao in Spain until the establishment of Guggenheim Museum in 1997. Since then, the city has attracted lots of visitors. I think no matter where you go, you go to a city to see its architecture. And we usually understand the culture of a city by looking at their buildings, such as when we go to Rome, we go to the Colosseum and Saint Peter’s Basilica.

The high density and skyscrapers in Hong Kong show how precious land is here. The city is a mix of old and new, and that is reflected in our buildings too. You can see a traditional newspaper kiosk just right next to a new and tall commercial building. This is what makes the city special.

Which three buildings in Hong Kong do you think could represent the city the most? Why?

The first that came across my mind is Hong Kong City Hall in Central. Many music and art events had happened there. It has witnessed the history of Hong Kong. The setting of the seats and the lighting of the building also represented the architectural style in the 1960s.

Secondly, the International Finance Centre represents Hong Kong’s identity as a finance hub. Its height has made it the city’s landmark that has witnessed economic development.

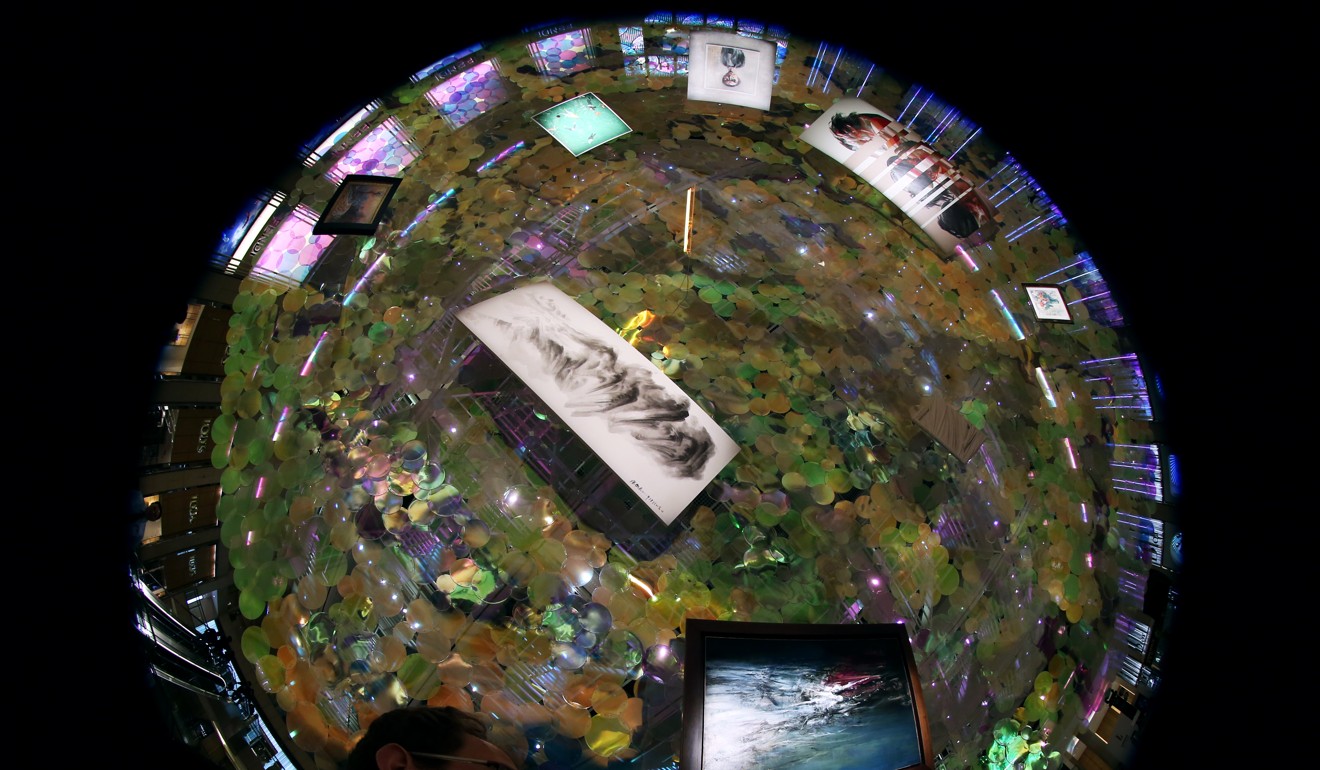

When it comes to art and culture, I hope my recent project H Queen’s can represent Hong Kong in this area. It is a mixture of commercial and idealistic, which I think is what Hong Kong needs now. [H Queen’s on Queen’s Road Central is designed to be at the centre of Hong Kong’s art and lifestyle. The development houses non-traditional spaces for exhibition with the interest of promoting the arts as well as expanding the audience for art.

Some criticise Hong Kong’s excessive high-rises for causing heat and pollutants to shroud the concrete jungle. What are your thoughts on the city’s urban planning?

Given the lack of space in Hong Kong, it is quite difficult to have great urban planning. But I think urban planners and developers should be more creative – instead of just building high-rise, we should build both tall and short towers at the same time. The idea of just building high-rises needs to be changed. It is common to see only tall buildings at a residential cluster, but I think it is possible to have tall buildings at the back and villa-style houses at the front. Then, we might be able to improve the airflow problem.

I hope people realise that we should be not only moving upwards when it comes to urban development. We should think more about street-level development. When property developers are thinking of how to sell more flats, they should also try to strive a balance between making money and good urban planning.

Singapore is considered to be the leader of green building in Asia. What can Hong Kong learn from them?

Developers in Singapore are given incentives by local authorities for well-designed buildings. But Hong Kong does not have that. In Hong Kong, as long as you stick to the regulations, it doesn’t really matter how your buildings look. There is no encouragement for developers to build a better looking and greener building. More and more new buildings in Shenzhen look very modern and have a sense of space. They are built from a human perspective. But Hong Kong still has a lot of catching up to do.

When did you realise you have a strong interest in architectural design?

I have always been an art lover. I think architectural is very similar to visual art. My interest in architectural design became stronger when I studied in university. I remember I started paying attention to art since I was a child. For example, when I travelled with my family at a younger age, I would go to local art galleries and try to get to know the local artists. I think my love for art has something to do with my personality. I was a quiet child who loved drawings and reading very much.

I did not come from a very arty family. My father is a Malaysian property developer, who worked with lots of architects and he thought my character was a good fit for pursuing that industry. He has been very encouraging in my career.

You had worked in Boston for five years before returning to Hong Kong in 1987. Why you decided to come back?

Living and working in the United States could be quite tough in the old days. At that time, the Chinese community there faced a glass ceiling. In the architecture field, it is very hard for Chinese architects to get promoted. It was a social norm back then, which I found a bit unfair. I had just got married at that time and needed to take care of my son, so I decided to come back to Hong Kong. But I was not confident that my career would be successful. I told myself to try it out for two to three years, and if it did not work out well, I would move my family somewhere else. When I first came back, I worked for a local developer for a few years. It went quite well. At that time, the US and European economies were declining, so I thought it might be better for me to stay in Hong Kong.

DESIGNS FOR A LIFE: HOW WILLIAM LIM RELAXES

What is your favourite place to travel?

I have been to Venice in Italy with my family quite a few times in the past few years because of the international architecture exhibition La Biennale di Venezia. Venice is a beautiful city and the exhibition is definitely worth going to.

Who is your favourite singer?

British singer-songwriter Sam Smith recently became my favourite. He is very talented to be able to write so many good songs. He has his own musical style.

What is your favourite film and why?

La La Land. It is a very good musical and reminds me of the old times. The film is about how two people pursue their dreams, which I think is important for everyone. I encourage my sons to fight for their dreams. I think the film is also a breakthrough in the industry, as not many directors have made a film like this in recent years.

What do you miss the most from the United States?

Watching the green leaves turning to yellow in autumn.

What do you usually do for fun?

I go to art exhibitions. I also like going to the countryside and beaches. What makes Hong Kong special is that people can get to the nature from city centre in 30 minutes.

Who has influenced the most in your career?

I am a fan of Le Corbusier, the late Swiss-French architect. I was largely influenced by him, especially when I was still a student, as his architectural design focused on a human perspective. He also emphasised the importance of green buildings. I admired the artistic side of him – he was not only an architect but an artist, producing lots of oil paintings and sculptures.

What is your favourite cocktail?

Mojito. It is made from herbs, so I think it is healthier than other drinks.