Those seeds from China: how a likely marketing tool fed conspiracy fears in the US

- The mailings this summer of unsolicited seeds to the US and elsewhere raised concerns of coronavirus and other contagions

- An investigation found many fake shipping labels, and experts said the packages fit the profile of ‘brushing’ operations to improve e-commerce rankings

Onion farmer Chris Pawelski of Warwick, New York, was curious in July when he found a package in his postbox that he had not ordered.

The shipping label indicated it came from Shenzhen, a technology hub in southern China. It was also printed with “wire connector” in English and “rings” in Chinese.

When Pawelski, 53, opened it, he found neither a wire connector nor jewellery, but a tiny plastic bag of mixed seeds – one of thousands of people around the world who received such seeds in recent months.

US recipients warned not to plant unsolicited seeds mailed from China

“I have no beef with China, the whole trade war doesn’t affect me at all,” he said. “On the other hand, I know there is tension going on, you never know what people might be trying to do. So better be safe than sorry.”

Pawelski immediately called the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, a division of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and mailed the seeds to the federal agency hours later.

While some initial reports about the mailings raised concerns and conspiracy theories in the time of Covid-19, e-commerce analysts said the packages were probably just examples of “brushing” – a tactic used by online sellers (many located in China’s manufacturing hubs) to boost the rankings of their products on shopping platforms.

Tracking the seeds

Little information about the senders could be learned from the packages that were apparently shipped from China across the world. Governments of countries including Britain, Australia, Canada and Japan warned their citizens against planting the seeds.

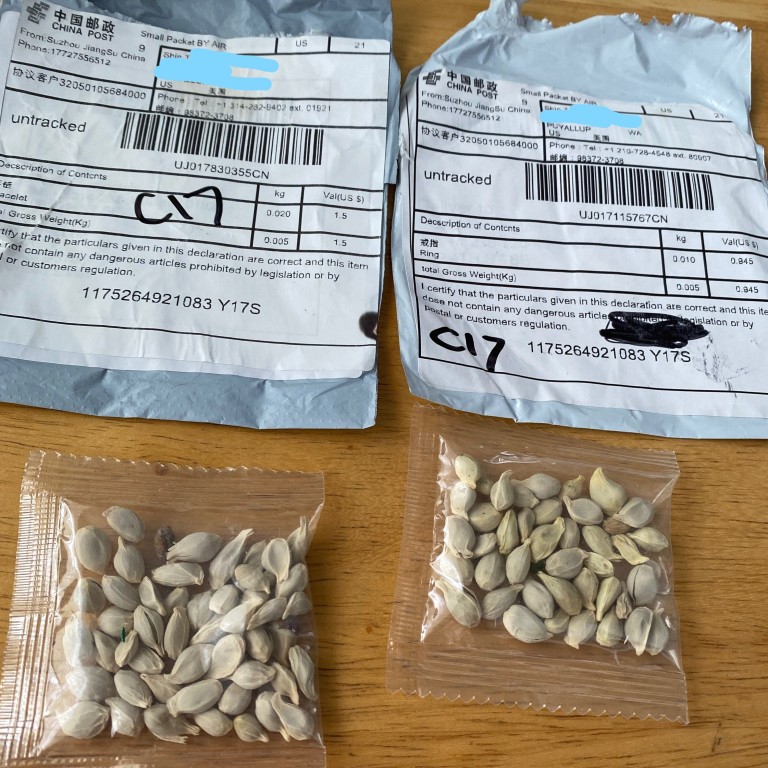

Pictures of them, posted online by recipients and authorities, carried “China Post” labels and were postmarked from several Chinese cities, including Shenzhen, Suzhou and Putian.

Some shipping numbers had no tracking information. A South China Morning Post investigation was able to identify 18 valid tracking numbers, and they indicated the packages had been sent out from late January to July. Some parcels took half a year to travel from China to the US.

The Post called the Chinese telephone numbers on the shipping labels. Three were answered.

One man surnamed Xu identified himself as a China Post employee who handled overseas shipments in Shanghai.

He said that he was not aware of any seed packages and that the staff there sometimes put their own contact information as return addresses on labels.

Mystery seeds: Beijing offers to help US investigate source of packages

Another phone number led to a man in Shenzhen, who declined to identify himself. He said he owned an e-commerce storage company but had no idea why his number ended up on the seed packages.

“Why did they have my phone number?” the man said after learning his number was printed on multiple US-bound seed packages. “I have no idea. My god, will it affect me personally?”

A third man based in Putian in the southeastern province of Fujian also declined to identify himself and would not discuss the packages.

Both China and the US say they are investigating. Beijing said the China Post shipping labels were forged and that it had asked postal authorities in other countries to intercept any such falsified packages.

The USDA said in August it had identified some of the companies that sent the seeds and that it needed Chinese authorities for help investigating them.

“We don’t have any evidence indicating this is something other than a ‘brushing scam’, where people receive unsolicited items from a seller who then posts false customer reviews to boost sales,” the USDA said in an online statement.

“USDA is currently collecting seed packages from recipients and will test their contents and determine if they contain anything that could be of concern to US agriculture or the environment.”

Conspiracy theories

The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service said the seeds were of at least 14 types of plants, including mustard, morning glory, cabbage, mint, rosemary, lavender and roses.

It remains unclear how many unsolicited seed packages were mailed to the US but a count by the state of Louisiana’s agriculture and forestry department put the number at about 16,000 specimens, including as many as 5,000 species.

The department also said the USDA had identified 44 countries of origin, without providing details.

On Twitter and Reddit, people joked about growing monsters from the seeds or contracting coronavirus from them.

Brushing schemes

For Chinese merchants, who dominate shopping sites globally, brushing improves the rankings of their products by tricking the platform’s algorithms, which favours high sales and positive reviews.

In one variation, the brushers place orders with their own fake shopping accounts. They then send parcels to overseas addresses. The packages could contain cheap items – or even be empty.

After the packages are delivered, the shopping sites recognise the orders as valid and let brushers post positive reviews.

That is likely how most unsolicited parcels from China are generated. Internet users have shared pictures of items that arrived in unsolicited, mysterious packages, from toys, sunglasses to jewellery and, most recently, masks.

It is unclear how brushers get hold of the names and addresses of the people they ship to.

Pawelski said his information might have been compromised when he ordered electronics and lingerie for his wife from Chinese merchants on eBay.

Cat and mouse

Chinese authorities have been grappling with brushing for years. The country’s e-commerce law, enacted last year, has classified brushing as a form of fake transaction and made it illegal.

But brushing services remain widely available in China for both domestic and international shopping platforms.

Chen, a Shenzhen-based electronics seller who declined to provide his full name, said he regularly hired brushing agents to help boost the rankings of his products on Amazon.

“It burns a lot of money to get an Amazon shop going,” he said. “It doesn’t work without brushing.”

The Post contacted more than 10 professional brushers in China and was offered various plans for international shopping sites including Amazon, AliExpress and Wish.

AliExpress is owned by Alibaba Group, which also owns the Post.

Amazon, Wish and eBay did not respond to requests for comment.

Alibaba’s Taobao and AliExpress said brushing was an industry-wide issue and that they had been working with authorities to identity and penalise merchants who manipulated transactions.

Ma Ce, an e-commerce lawyer based in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou, said law enforcement often did not have the capacity to look into the large army of brushers.

Large platforms might be concerned with brushing disrupting their regular advertising business, while small shopping sites had less incentive to crack down, because the fake orders could also improve their performance numbers, he said.

Luyi Yang, an assistant professor in information technology at University of California, Berkeley, said that despite increasing security from authorities, brushing was likely to persist in the short run.

“For the online merchants there is just so much at stake,” he said. “They really don’t have a good alternative in such a competitive environment. They really have to resort to brushing to stand out among the crowd.”

He said that outside e-commerce, brushing was also widespread in music, movie, book and social media industries. For example, music producers may falsify downloads so their works can be ranked higher in the charts.

“It is a data-driven world. You always want data to speak for itself,” he said. “But the more we rely on data, the more the sellers have incentives to manipulate or falsify data.”