Xinjiang starts to ease Covid-19 lockdown after surge in social media anger

- Residents have been trapped in their homes for more than a month despite no new cases for past 10 days

- Censored complaints mostly from Han Chinese, highlighting difficulties in assessing reports from largely Muslim region

The city of 3.5 million people, which has been in strict lockdown since mid-July, has reported no new cases of the disease since August 16.

01:26

Capital of China’s Xinjiang region placed under lockdown as coronavirus returns

At least two people in Xinjiang who left their houses without permission were handcuffed to fences as a punishment, according to photos circulating on Chinese media. However, the South China Morning Post was unable to confirm the authenticity of the photos, or how frequently this had occurred.

On Monday the Urumqi city authorities announced an easing of restrictions for some communities, with residents now permitted to carry out individual activities within their own compounds. “Businesses in communities such as supermarkets, convenience stores and fruit shops may reopen in the specified hours,” a notice on the local government website said.

Many of the posted complaints used hashtags for other cities, such as Beijing or Shanghai, after residents said comments under Urumqi or Xinjiang were censored. The Post was unable to verify all accounts, but conversations with Urumqi residents or those with family in the city indicated restrictions had been severe.

The Xinjiang region, with its large Muslim ethnic minority population, is especially sensitive for Beijing, which has built a vast surveillance and security network in the area to counter what it calls separatists and terrorists. The UN has said hundreds of thousands of Uygurs and other minorities are detained in internment facilities.

A former Urumqi resident, who gave her name as Snow, said her Weibo post was deleted after she put up a video filmed in the city showing a police officer yelling through a loudspeaker at a resident who left home during lockdown. She declined to give her full name, saying she needed to protect family members in the region from retaliation by the authorities.

Could Beijing 2022 be hit by boycott over Xinjiang?

“The Weibo posts by so many people were deleted. This is what I’m the angriest about, there are no channels for feedback. This makes Xinjiang residents feel like there is no place they can voice their complaints,” she said.

According to Snow, 28, a friend in Urumqi was forced to stay inside her home for a month and threatened with arrest on the one occasion she stepped outside to remove rubbish. The friend said front doors of homes had been taped over by the authorities so they could check if they had been opened.

On Monday, the Urumqi authorities also published the personal phone numbers of 19 district officials, including the city’s Communist Party Secretary Xu Hairong and Mayor Yasheng Sidike, saying they would do all they could to address residents’ concerns and problems.

Calls to the officials by the Post found most of the lines engaged. Three were answered by secretaries or colleagues, while one call directly reached an official.

“Dabancheng area is strictly following the epidemic control orders from the local government and Communist Party,” an aide to Ding Zhijun, the district’s party secretary, said when asked about the online complaints and censorship. He directed the Post to call the city’s propaganda department, which declined to comment.

A writer and Xinjiang native based in Beijing known as Zhu You wrote in a viral WeChat post on August 23 that the lockdown measures lacked consideration for residents. “Firstly, [with most of the cases] in one city, Urumqi, the entire Xinjiang region has been locked down,” Zhu wrote.

As a result, commodity prices surged, grocery supplies became unstable, students attending schools outside the region were stranded, and people’s mental health had suffered, Zhu said. When contacted by the Post through WeChat, Zhu declined to comment further.

Zhu deleted the post on Sunday evening after being contacted by local cybersecurity personnel, according to an update shared with the Post. Screenshots uploaded by other Weibo users have also been removed.

Wang Yaqiu, a China researcher at Human Rights Watch, said Xinjiang authorities had responded to the Covid-19 outbreak with the same mentality and tools used for surveillance of residents in past crackdowns on Uygurs and other minorities in the region.

However, most of the complaints on social media appear to have been posted by ethnic Han Chinese and all of the people spoken to by the Post were of Han ethnicity. It is difficult to assess the situation faced by the region’s minorities, who are under close surveillance and could face reprisals for talking to reporters.

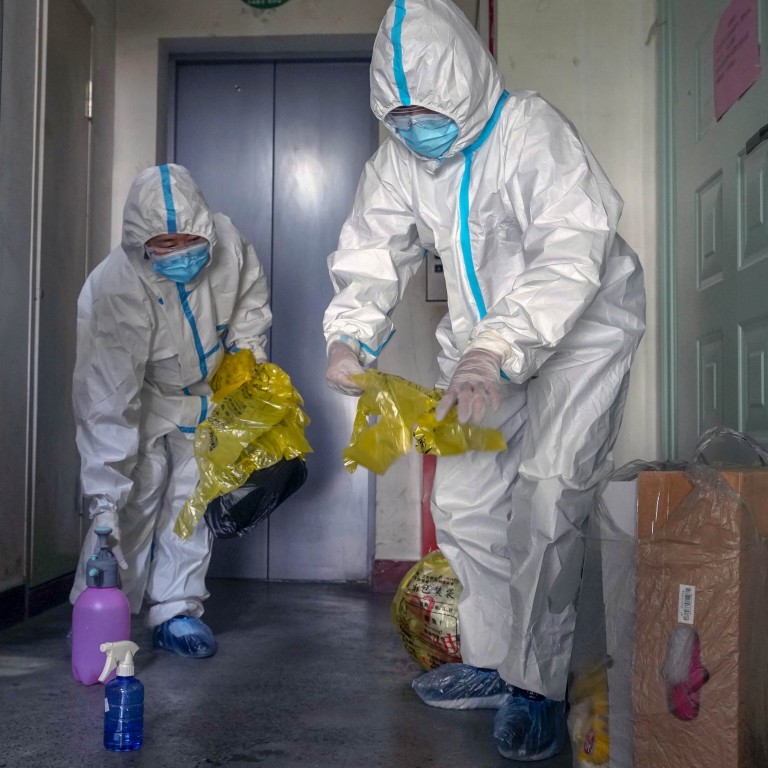

Urumqi authorities said residential compounds had been sealed off and that more than 60,000 volunteers were serving residents’ daily needs, such as delivering groceries and medicines. The volunteers also patrolled 882 compounds in the city and residents were “guided” to not venture outside.

Chinese traditional medicine for Covid-19 becomes money tree

Weibo users heavily criticised the apparent forced use of traditional Chinese medicine after a video was posted – and later censored – showing people said to be in Urumqi lining up to drink a concoction to treat Covid-19.

The Post was unable to verify the video, in which a woman can be heard in an off-screen narration saying “the 15 residents of the community are taking their medicine together this morning. Today is August 20. Drink quickly”.

Dr Li Fengsen, from a designated Covid-19 hospital in Urumqi, said in a July briefing by the regional government that traditional Chinese medicine was part of the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of coronavirus patients.

Beijing pushes traditional Chinese medicine as coronavirus treatment

According to Snow, her family and friends in Xinjiang had been given traditional Chinese medicine and it was mandatory in some neighbourhoods for residents to take it every day. A screenshot shared by Snow with the Post showed a WeChat group of close to 30 residents posting videos of themselves drinking the medicine, which she said was required as proof of compliance.

“Everyone, as already clearly explained when we gave out the medicine, must send videos of yourself taking the medicine three times a day and it must be a complete video showing you taking it from start to finish,” said a message posted by a community worker in the group.

Two other Urumqi residents confirmed to the Post that they had also been required to take the treatment.