Why foreign students along the belt and road are jostling to enrol in China’s universities

Squeezed out of college places in their home countries and drawn by Chinese scholarships, students from nations along the route of Beijing’s massive infrastructure plan are pouring into China, reshaping regional education

When she began applying for admission to universities in pursuit of a master’s degree, Pakistan native Maira Tahir aimed high and far, sending out applications across a huge swathe of the globe.

Her requests to be considered for a spot at a top school landed on the desks of admissions officers in the United States, Finland – and China.

In the end, she accepted an offer of admission from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, an old public research university in China known as “The MIT of the East”.

What helped Tahir make her decision was not just the school's reputation and tradition – it was founded in 1896 at the edict of the 10th emperor of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) – but something more tangible: a scholarship offer.

“I thought knowing Chinese language and about the culture would be a bonus to my CV,” said Tahir, 23, who will study new media and take required courses in Chinese language and culture at the school.

“The school has a great reputation, and they gave out a really nice scholarship,” Tahir said. “I was accepted in the US, but I was not going to get a scholarship.”

For Tahir, going to the Shanghai university caps off years of watching China’s influence grow over her home country.

Along with the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in 2015 – a US$62 billion collection of infrastructure projects China is building – has come a flurry of interest in building business ties and opening Chinese language centres in universities.

As Tahir has observed China’s outward push, she is also a product of China’s painstaking efforts to draw students to its institutions of higher learning. Just under half a million international students now study across 31 provinces and regions in China, about as many as in Britain.

And like Tahir, about two-thirds of China’s international students – numbering 317,000 last year – hail from countries that have partnered with China in the “Belt and Road Initiative”, Beijing’s massive and ambitious US$1 trillion infrastructure plan.

The influx of international students to Chinese schools is part of a carefully conceived but little publicised aspect of the global project: education.

The official guidelines for the belt and road educational initiative, released in 2016, include mutual recognition of scholarly degrees between nations and encourage collaboration between nations' universities.

But the initiative’s impact can largely be felt on China’s campuses, where scholarship funding and the creation of English-language international departments – often with promotional Facebook pages despite that site being blocked in China – are beckoning students from across the belt and road and beyond.

The initiative marks a slight shift in focus from China’s long-standing support of international students from developing African countries like Somalia and Sudan, whose numbers have increased rapidly since 2003.

In the past year alone, enrolment from belt and road partner nations has jumped 12 per cent to 317,000 students.

Meanwhile, students are moving away from short-term Chinese language study. Almost half of all international students in China are pursuing bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral degrees, with the number increasing 15 per cent from 2016 to 2017, according to Ministry of Education statistics.

Alan Cheung, a professor of educational administration and policy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said part of the logic behind China’s move to attract more international students is to train a workforce that will help it attain the financial, infrastructural and policy goals laid out in the “Belt and Road Initiative”.

“All of these goals require very skilled and educated manpower, both in China and in the other countries,” Cheung said.

“There are around 60 countries in the belt and road and some are still so-called developing countries. They need a lot of training, which can be mutually beneficial in the long run.”

EXTENSIVE FUNDING

To drive this educational goal, China’s government has rolled out an extensive system of scholarship funding for international students.

Notably, these students are exempt from taking the gaokao, the gruelling university placement test for local residents. Instead, students from abroad can apply for admission to schools’ international programmes and for scholarships through a separate system. They can also be placed in programmes via other means.

This was the case for Biku Maharjan.

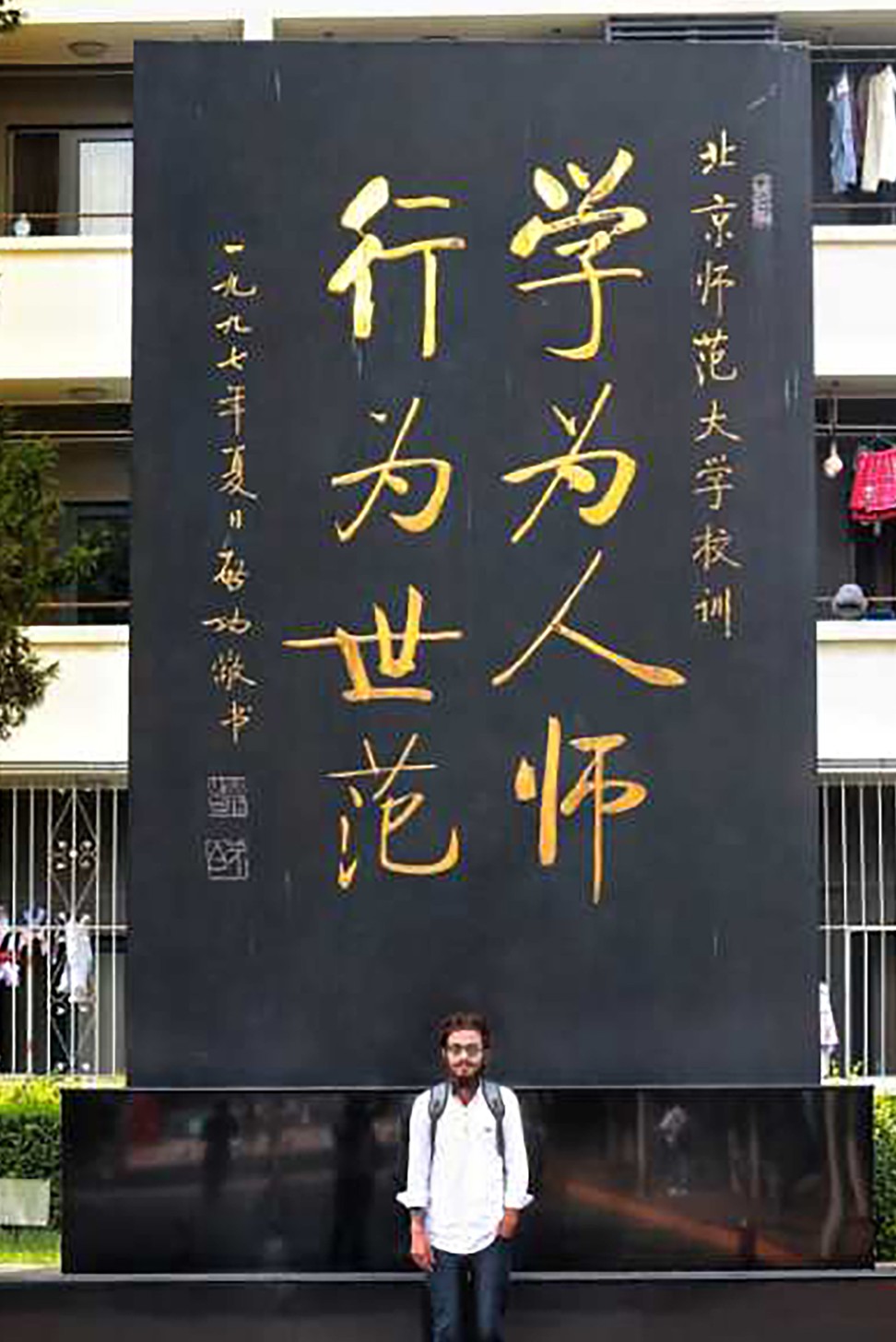

Growing up in Kathmandu Valley in Nepal, he thought little about China. Ultimately, however, he found himself one of 50 Nepali students selected to study for an expenses-paid bachelor’s degree in Chinese language and culture at Beijing Normal University, just months after he started taking a Chinese course at a Kathmandu Confucius Institute.

“Learning Chinese was not a big priority in our country. It never was,” said Maharjan, who was offered a place at Beijing Normal after submitting an application to the Confucius Institute.

“In fact, if I had to pay for the whole course, I wouldn’t have applied at all,” he said. “My family could barely afford it. But coming to China has been an open platform for me to explore my choices.”

While the authorities have disclosed no official budgetary total for the range of scholarships offered to international students, the number of students receiving central government funding has increased by 70 per cent since 2012, with support ranging from tuition aid to full packages that include monthly stipends of several thousand yuan.

The government earmarks 10,000 scholarships for belt and road students each year, according to state media.

Of the nearly 50,000 government scholarships awarded in 2016, 61 per cent were awarded to students from belt and road countries, the Ministry of Education reported.

These figures do not include the array of scholarships offered at the university level, as well as Confucius Institute scholarships, such as the one Maharjan is using to fund his bachelor’s degree studies.

BETTER OPPORTUNITIES

While the promise of scholarship money is a big draw for students, so are other sweeteners that intersect with a variety of issues unique to each country.

Opportunities to use advanced technologies or apply for China-oriented jobs also heighten the appeal of studying at a Chinese university for students who come from countries that lag China in technology or that have overburdened higher education systems.

For Nandar Nyein Thu from Yangon, Myanmar, coming to China was not her original goal. But after her application to the China Scholarship Council for a grant in support of her education was approved, she knew it would be the most feasible way to obtain access to the more advanced laboratory facilities she saw as essential for her doctoral work.

“If I do research work in my country, it cannot be used in application, because my country is not developed in technology like China,” said Nandar, who now is pursuing a doctorate in control science and engineering at Harbin Engineering University.

In China, “we know the limits of technology, so we can work on very focused areas of research to advance technology”.

Nandar set up a Facebook page to help other students from Myanmar who are considering studying in China to navigate the system and adjust to life in the country.

She plans to continue the service after she finishes her degree and returns to Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city, to teach at her local university.

Electrical engineering major Saha Pranto said he felt the quality of his bachelor's degree courses would have been roughly the same if he had pursued his studies at home in Bangladesh; but he didn’t have the option to do so.

The limited number of spaces at his country’s public universities prevented him from receiving a placement in his chosen speciality, he said.

“I didn’t have any plan to study at a private university, so I decided to come to China,” he said.

Though his scholarship provided just enough funds to cover his tuition, leaving him to pay for his room and board on his own, Pranto, who is now in his third year at the China Three Gorges University in Hubei, said he feels China was his best chance for continuing his education.

But some observers say overcapacity at universities elsewhere in the world, rather than an increase in the prestige in Chinese universities, is what is driving Central Asian students to their eastward neighbour.

That is the view of Michal Bogusz, senior analyst at the Centre for Eastern Studies, in Warsaw, Poland.

“There are more and more students going to China studying,” Bogusz said. “But it is related to the situation that local universities don’t have enough capacity to give placement to all those who want to study there, so these students will go to Europe or go to China.”

Moreover, China’s culture and its nascent reputation as a centre for higher learning make it a viable second choice for Central Asia and Eastern European students more culturally oriented towards Russia and Europe, he said.

“From their perspective it is easier to adapt to local conditions here than in China,” he said, referring to study in Europe.

Alan Cheung of the Chinese University of Hong Kong also believes that China has a way to go to build the international reputation of its schools up to an elite level.

“There are some great universities that offer great programmes at the STEM level, but they may have a hard time getting good students,” he said. “China is competing with other countries for the best and brightest.”

But Cheung predicts growth will continue from China’s neighbouring regions, including Central Asia, where China has been increasing its presence since President Xi Jinping launched the “Belt and Road Initiative” in a speech in Kazakhstan in 2013.

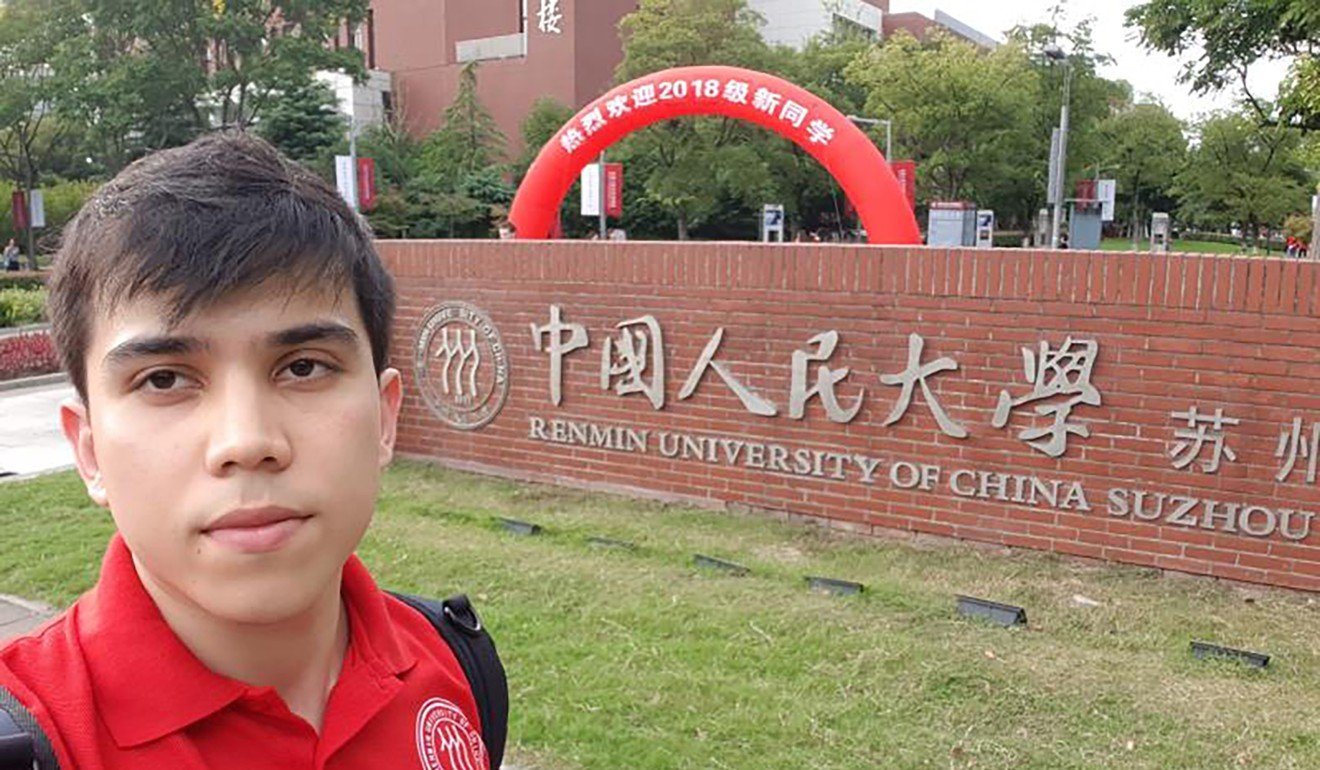

Shokhrukh Ashrafi is one student from this region who accepted full government funding for a programme that offered courses specifically related to belt and road projects.

The native of Dushanbe, Tajikistan recently began pursuing a master’s degree in contemporary Chinese studies at the newly opened Silk Road School, an offshoot institute of Renmin University on the research university’s campus in Suzhou, in east China’s Jiangsu province.

The institution, which was launched in May, strives to recruit students from countries and regions along the belt and road, offering specialisations in Chinese politics, Chinese economy, Chinese law and Chinese culture.

Although Ashrafi said he was lured to the school by the opportunity to enhance the Chinese studies he took while earning a bachelor’s degree in international relations back home, he also is mindful of the larger possibilities tied to studying in China.

“The bordering countries like Tajikistan and Pakistan, Russia and others, are all of crucial importance to China,” he said.

“Having students that have studied in China that are familiar with China and its people and political culture, I think China may use these people in the future when promoting Chinese interests in these countries,” he said.

He said he has already seen this strategy applied in the business sector in Tajikistan.

Nevertheless, he said he was unsure of the extent to which collaboration ultimately would take off and increase the value of knowledge about China in his home country.

“Although the government supports the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ and keeps saying they are ready for these kinds of initiatives, I don’t know how useful Tajikistan can be, except for the transportation of goods from China,” he said.

“My country is moving a bit slowly, but I hope this will change.”