China’s first space station Tiangong-1: the story of its life and death

A symbol of the second stage of China’s three-step space strategy outlined in the 1990s, it achieved milestones while being a prototype for its successor

One day after April Fools’ Day 2018, China’s first space station hurtled through the atmosphere. Most parts were burnt up during the process, but parts of it fell into the ocean.

It marked the end of China’s most significant space project, but Tiangong-1 was just the start of its space ambitions coming to fruition.

Since the 1970s, China has had big ambitions for space exploration but lagged behind Russia and the US until President Jiang Zemin gave the green light for a manned space programme in 1992.

When Xi Jinping took power in 2012, he announced plans to turn China into a “space flight superpower” as a top priority for his government.

In the 1990s, China had launched a three-step strategy for its manned space programme. The first step was to send people into space, which it first achieved in 2003 with astronaut Yang Liwei, who orbited the Earth 14 times during a 21-hour space voyage.

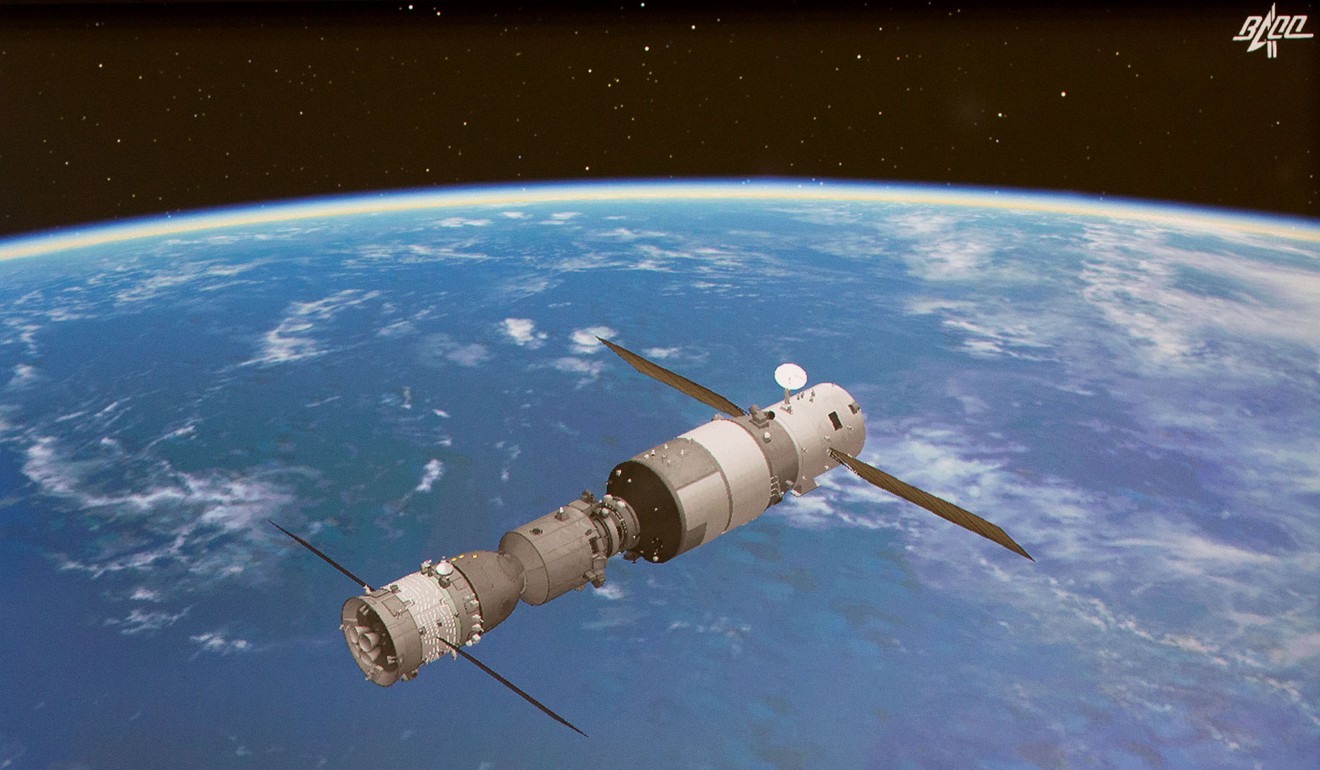

Eight years later in 2011, China unveiled its first space station, Tiangong-1 (which means “heavenly palace” in Mandarin).

Tiangong-1 was more of a prototype space station, a space test platform, used to prepare for the construction of a fully-fledged space station.

Its main goals were to allow astronauts to complete rendezvous missions and successfully dock with spacecraft.

Making history

Part of the second step in China’s space strategy, Tiangong-1 was hailed by Chinese state media as a breakthrough, because key technologies were successfully developed.

One of those was to create docking capabilities, which would make China one of only three countries to possess this and bring it one step closer to establishing its own fully operational space station.

The 10.4-metre, 8.5-tonne spacecraft, which was roughly the size of a school bus, comprised two parts: an experimental module, where spacecraft would dock and astronauts would live, work, communicate with ground staff and conduct experiments; and a resources module that would supply power for the spacecraft.

Although launched unmanned, Tiangong-1 was designed to accommodate three astronauts for up to two weeks at a time.

The plan was for it to remain in orbit for two years.

The launch

The spacecraft was first planned to be launched on August 30, 2011, but after the launch of a satellite failed on August 18, the date was postponed by a month.

Finally, on September 29, 2011, an unmanned Tiangong-1, carried by the Long March II-F T1 rocket, was launched into orbit.

President Hu Jintao watched the launch from a space flight control centre in Beijing, while Premier Wen Jiabao was present at the launch centre during take-off, reported Xinhua.

“This is a significant test. We’ve never done such a thing before,” Lu Jinrong, the launch centre’s chief engineer, reportedly said.

Xinhua also released a commentary stating: “We must soberly recognise that China’s space-station technology is still in its initial stage, compared to those of the US and Russia… But the launch of Tiangong-1 is the beginning of China’s efforts to narrow the gap.”

Overseas observers seemed to agree. Associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Taylor Fravel told CNN in 2011: “The test reflects China’s technological advances, funded by its rapid economic growth and facilitated by the military’s ballistic missile programme.”

Dockings

Around one month after its launch, China accomplished its first successful space docking procedure, 343km above the Earth’s surface, making it the third country behind the US and Russia to do so.

Explaining the complexity of the feat, Zhou Jianping, chief designer of China's manned space programme, said at the time: “To link up two vehicles travelling at 7.8km per second in orbit, with a margin of error of no more than 20cm, is like finding a needle in a haystack.”

The two spacecraft maintained orbit together for 12 days, before undocking and docking again, this time in the more difficult conditions of being in full sunlight. This is considered more challenging because the sunlight could interfere with the optical system’s performance.

The unmanned Shenzhou-8 craft later separated from the space station and returned to Earth, landing in Inner Mongolia.

Later in June 2012, the spacelab docked with Shenzhou-9, carrying Liu Yang, China’s first female astronaut, and two male astronauts, Jing Haipeng and Liu Wang. The launch date coincided with the anniversary of USSR cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the world’s first female space traveller, being launched into space.

After the astronauts entered the spacelab and stayed there for 10 days, the space flight undocked from Tiangong-1 and returned to Earth.

About a year later, Shenzhou-10 was sent to dock with the spacelab and three astronauts worked there for 12 days on maintenance of its facilities.

During their stay, the three astronauts staged a “space lesson”, doing some simple physics experiments in the space lab for Chinese pupils, broadcast to the nation.

In total, Tiangong-1 received six visitors and hosted three docking missions, which space authorities have said made “significant contributions to the development of China’s manned space mission”.

Last days

Tiangong-1 was originally planned to be decommissioned in 2013, but China decided to extend its service period for another three years for researchers “to collect experiment data”. It did not host any more manned missions.

After 1,630 days in orbit, Tiangong-1’s “functioning failed” and its data service was terminated, according to a China Manned Space Engineering Office statement in June 2016.

Researchers predicted the spacelab would re-enter the atmosphere in the second half of 2017, but a delay left some observers wondering whether it was out of control.

Last December, Zhu Congpeng, a top engineer at the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, said that Tiangong-1 was under continuous observation and did not pose a safety or environmental threat.

“It will burn up on entering the atmosphere and the remaining wreckage will fall into a designated area of the sea, without endangering the surface,” he said.

On April 1, 2018, China confirmed Tiangong-1 was set to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere the next day.

True enough, the space lab hurtled back to Earth a day later, burning up in the atmosphere and falling into a remote part of the Pacific Ocean.

Later Beijing decided there was little value in deploying a team to salvage its remains.

Legacy

A second space lab, Tiangong-2, was developed based on Tiangong-1 and sent into orbit in 2016.

About a month later, it docked successfully with Shenzhou-11. Tiangong-2 is still in orbit; it was originally meant to run for two years, but this may be extended to five years.

In 2017, China launched the Tianzhou-1 supply spacecraft, designed to deliver fuel, food, water and other supplies to Tiangong-2. It has since re-entered the atmosphere.

China plans to finish assembly of Tianhe-1, a large modular space station, and send it into space by 2023, bringing the country to the final stage of its three-step strategy.

The International Space Station is the only large-scale space station currently in orbit. It is expected to retire in 2028.