China’s brain drain to the US is ending, thanks to higher salaries and Donald Trump

Better salaries for postdoctoral research fellows and a more hostile atmosphere in America mean more Chinese scientists prefer to stay at home

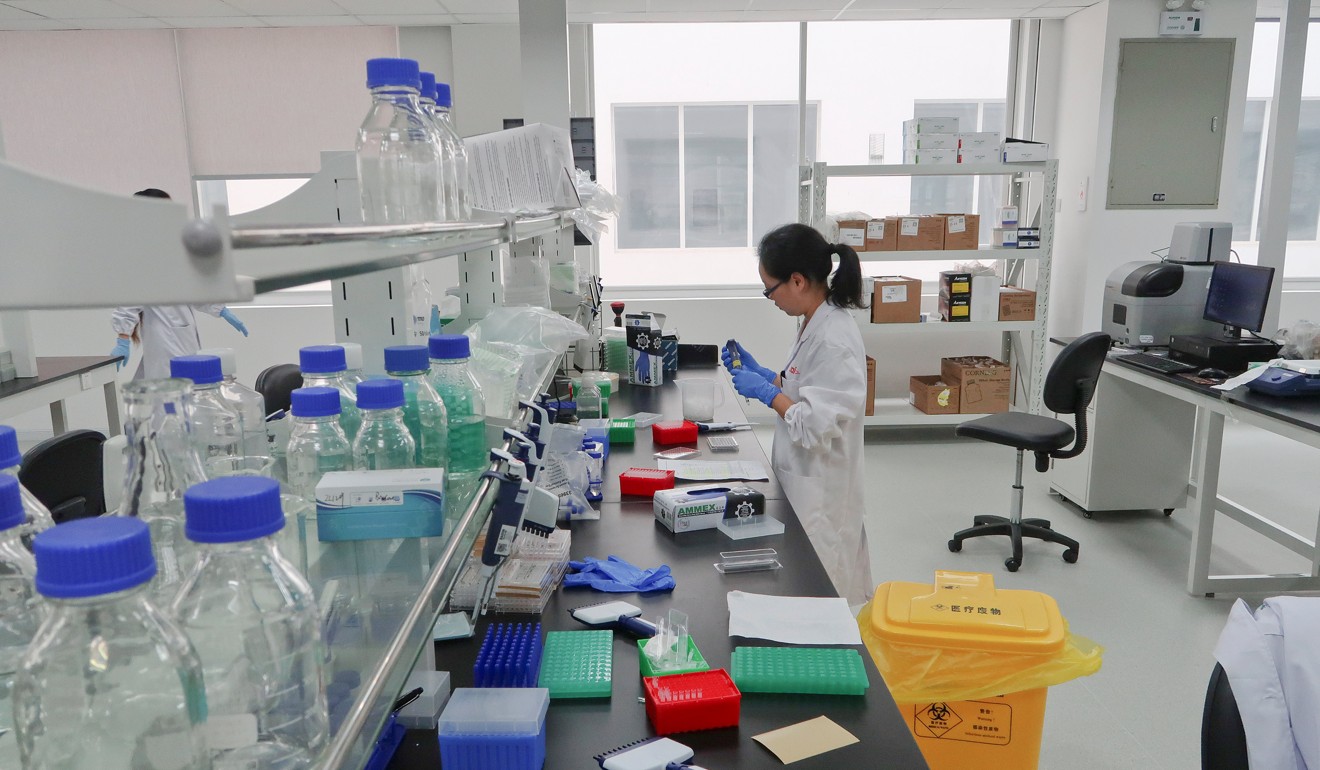

China appears to have successfully reversed a “brain drain” among top researchers who have gone overseas in droves for years, mostly to the United States.

Now, many of the country’s best and brightest scientists are staying put, as higher pay packages and changing perceptions of domestic scientists increase the appeal of local jobs.

Staunching the exodus of research talent from China is the administration of US President Donald Trump, whose aggressive moves have promoted a climate that is unfriendly to scientists of Chinese origin.

“The problem of the brain drain no longer exists,” said Chen Guoqiang, director of the Centre for Synthetic and System Biology at Tsinghua University, a top Beijing research institution. “One important reason is the salary. Another reason is Trump.”

China had about 600,000 students studying overseas last year, according to the latest statistics from the Ministry of Education, released in April.

More than half of them were studying in the US.

In past years, more than 95 per cent of Chinese students obtaining an advanced degree in a developed country chose to stay there after graduation. By the end of last year, however, more than 83 per cent had returned to China, most within the five years starting in 2012.

Despite the Trump administration’s restrictions on US-bound Chinese students and researchers, many young Chinese scientists have responded to those moves with a shrug given the pay is better back home.

The salary for one particular postdoctoral research fellowship in China now reaches up to 600,000 yuan (US$87,827) a year – nearly twice the average pay for the same job in the US, according to a hiring notice issued by a Chinese government research institute last month.

China eyes bigger role in world’s most powerful telescope project

“The base salary is 250,000 to 300,000 yuan per year … with a reward stipend for outstanding candidates from 100,000 to 300,000 yuan per year, so the gross annual salary will reach 350,000 to 600,000 yuan,” said the job advertisement.

It was issued on August 30 by Professor Zhou Yongjin’s team from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in the northeastern province of Liaoning.

Zhou’s team, which studied chemical production enzymes, has developed an award-winning technology for making new medicines. With research grants exceeding 18 million yuan last year, the team is hiring not one, but two postdoctoral researchers – with the same offers.

Postdocs are entry-level scientists who professionally conduct research after completing their doctoral studies. The job requires no work experience and is open to any recent graduate with a PhD degree in microbiology.

In an interview, a member of Zhou’s team confirmed the hiring details. “It is a reasonable salary. It is not the highest in the market,” said the team member, who requested anonymity, citing the sensitivity of pay-related issues.

In the US, the average annual salary for postdoctoral fellow is about US$47,000, according to glassdoor.com, a major salary reference website.

In the biomedical research sector, the salary is higher than the average. The National Institute of Health, for instance, pays US$51, 450 in average, but it is still far below the offer by Zhou’s team.

Although Chen said the salary offered by Zhou’s team was “very high”, he said it was unsurprising.

Chinese scientists’ income has increased rapidly in recent years, reaching more or less the same pay scale as their counterparts in the US and sometimes considerably more, according to Chen.

Of 60 recent graduates from Tsinghua’s PhD life science programmes, only five chose to go overseas. Among them, three have returned, Chen said.

The White House ramped up its aggressive moves against scientists of Chinese origin in June, when the US State Department started shortening visa stays for Chinese graduate students studying in sensitive research fields to one year from five.

Trump rails against China during dinner with executives

That action followed FBI director Christopher Wray’s assertion in February at a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing that spying by Chinese professors, scientists and students in the US constituted a “whole-of-society threat”.

“It’s not just in major cities,” the director said. “It’s in small ones as well; it’s across basically every discipline.”

In an official dinner with senior business executives last month, Trump hinted that almost every student that comes over to the US from China was “a spy”.

In this climate, “unless there is an irresistible offer, such as a post in a very, very top laboratory, most people choose to avoid America,” Chen said.

The brain drain’s apparent end comes as China’s scientific research cuts across multiple frontiers with the potential to change the world.

Numerous new drugs to cure major diseases such as cancer, Aids and Alzheimer’s are in the pipeline; superconducting and quantum computers that can process and store vast amounts of data using less energy than classic computers are under construction; unprecedented applications of artificial intelligence technology are being used in business and factories; and new weapons, including hypersonic vehicles, unmanned stealth aircraft and high-power directed energy cannons, are close to field deployment.

The booming research sector’s need for talent is enormous.

Most postdocs are in their late twenties or early thirties, a period regarded by some as the most productive and creative in a scientist’s career.

Chinese scientists clone monkeys. Will humans be next?

Taking on a postdoc job is the first move for many scientists before they head on to permanent positions.

In China, more than 10,000 PhD graduates entered postdoctoral programmes in 2016, according to China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. They were sought after by more than 6,000 research institutes, universities and companies certified by the central government to hire postdoctoral researchers.

A managing official at the foundation said official data on postdoc salaries was unavailable because wages vary from one place to another; but he said most postdocs should earn between 200,000 and 400,000 yuan this year.

That is three times the average wage in China.

“As competition for talent pushes salaries higher and higher, the incentive to leave (China) has become lower and lower,” said the official, who asked not to be identified. “It is a trend very much welcomed by the government.”

Liu Yang, a postdoc in the School of Aerospace Engineering at Beijing Institute of Technology, said she and her colleagues were aware of growing xenophobia in the US. They refused to consider studying or working in America as long as Trump was in office, she said.

Can China build a superconducting computer to change the world?

Liu’s studies included investigating how to send spacecraft to an asteroid – either to push the wandering star off an Earth-crashing trajectory or mine its valuable ores. Space research is one of the most guarded US sectors, as the technology could be used either for military or civilian purposes.

“I am definitely not going to a country with increasing hostility against Chinese researchers,” Liu said.

The monthly pay to postdocs used to be between 2,000 and 3,000 yuan a month – “barely enough for survival”, according to Liu. In recent years, the salary has seen a “significant boost”. Though the pay tends to vary among teams, Liu said a postdoc nowadays should have no problem earning more than 200,000 yuan a year.

Liu’s team collaborated with a private space company in Zhuhai, Guangdong to develop technology and hardware for Chinese deep space exploration missions such as capturing and mining asteroids.

Liu attributed the high salary for postdocs partly to a lack of job security, since the role usually ends after two or three years. Unemployed researchers often turn to working as university lecturers or assistant professors, which might bring a pay cut but provide greater stability.

The Chinese government’s effort to reverse the brain drain, however, is built on more than a pay increase.

Chinese scientists snip mutant DNA to fix human embryo gene

In the past, young Chinese scientists did not regard remaining in China to be in a doctoral or postdoc programme as an attractive option. They preferred leaving for another country, especially to the US or Europe, to gain Western experience that was usually considered a pathway to better-paying, higher ranking jobs once the researchers returned to China.

Now some top Chinese research institutes and universities are trying to correct the bias.

Bai Chunli, president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, told state media last month that the organisation was conducting an unprecedented review of its talent evaluation system.

Liu Zhen, a postdoc in the academy’s Institute of Neuroscience in Shanghai who contributed important research to the world’s first cloning of a monkey, was recently promoted to a position as a professor-level researcher with sufficient funding to establish his own team and a laboratory. Liu, who has not worked or studied overseas, is only 30 years old.

“To young scholars who make big contributions, especially doctoral students and postdocs, we will use special policy to give them funding, salary and welfare equivalent to or even higher than those for high quality talents from overseas,” Bai was quoted by China Youth Daily as saying.

“Graduates no longer need to go overseas for branding.”

But Leng Fuhai, a researcher with the Institutes of Science and Development, a major science and technology think tank in Beijing, said young scientists who chose to stay face no less pressure than those going overseas.

In big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, the cost of living is increasing rapidly and the salary increases cannot match the pace of skyrocketing property prices, according to Leng.

“Nearly all the talented postdocs I know cannot stay in Beijing because they cannot afford a tiny flat,” he said. “Many have returned to the smaller cities where they came from, losing the opportunity to participate in some big projects.

“This may hurt the development of their academic career,” he said.

Some young Chinese scientists have been prevented from leaving China against their will because the country’s authorities feared they would leak technical secrets to overseas rivals.

Why China’s overseas students struggle after coming home

Shao Yangyang, a doctoral student at the Shanghai Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, who took part in creating the world’s first functional single chromosome yeast, was “persuaded” to drop her application for a postdoc position at a competing laboratory in New York, according to researchers close to the team.

Professor Qin Zhongjun, Shao’s mentor and the team’s lead scientist, confirmed that Shao would remain in Qin’s laboratory “for a while” but declined to give more details or comment.

“For the career development of the student, I hope she will go overseas; but for the interest of the country, I really hope to keep her,” Qin told Wenhui Bao, a major daily newspaper in Shanghai last month.

“Losing an outstanding PhD student not only means losing a golden period of creative research, but giving the innovative methods and ideas developed in a domestic laboratory to competitors,” he said.