How political and economic pressure led to Beijing’s abrupt U-turn on zero-Covid

- Xi acknowledged frustrations about pandemic-control policies at meeting in December

- Sources say leading cadres in major economic powerhouses reported dire situations

After three years of tough pandemic controls, China’s sudden U-turn on its zero-Covid policy last month has brought relief but also anxiety that the country is unprepared for the surge in cases. In the first of a five-part series on the policy change and its impact, William Zheng looks at the political factors behind Beijing’s decision to reopen.

In the last two months of 2022, the world watched in astonishment as China made an abrupt U-turn on its strict zero-Covid strategy, calling off three years of mass testing and lockdowns and becoming the last major economy to reopen its borders to the world.

The reopening, with no timetable or road map announced beforehand, also caught most members of the Chinese public, frontline medical workers and even local policymakers by surprise.

One health official said an earlier reopening plan would have seen the process start after the annual meetings of the national legislature and the country’s top political advisory body in March.

“March would have been a better time,” he said. “We would have had more time to shore up the vaccination rate, especially among senior citizens.”

The official added that higher temperatures would also have helped slow down the spread of infections.

That plan was based on a gradual approach to relaxing controls that aimed to achieve full reopening before September, when China will host the delayed 2022 Asian Games in Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang province.

Another advantage of reopening in March was that key appointments to the State Council, China’s cabinet, would have been finalised, the official, who requested anonymity, said.

“We would have had a clear command chain,” he said.

China’s Li Qiang makes speech for State Council, hinting at premier’s job

Xi loyalists set to take up key government roles, especially Premier Li Keqiang’s successor Li Qiang, will have to wait until the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress in March for formal appointment to the new cabinet.

Four vice-premiers and Xi’s chief of staff have also yet to be formally appointed.

For almost three years, the zero-Covid strategy backed by Xi focused on early identification of infections by mass testing and quick quarantining of the infected, their close contacts, and even the close contacts of close contacts.

It managed to keep China largely Covid-free until July last year, while the rest of the world saw millions of deaths during the same period. The ruling Communist Party hailed the achievement as clear evidence of the superiority of the Chinese model of governance over that of Western democracies, especially the United States.

China’s national broadcaster, China Central Television, slammed the idea of “living with the virus” as an irresponsible public health policy and singled out the US as the “the biggest failure in the global pandemic fight”, while proudly proclaiming that China had “prioritised people’s lives despite the economic damage”.

Coronavirus: China sticks to zero-Covid as management failures and misery mount

While a small top-level meeting chaired by Xi on November 10 sent out a clear signal that the draconian pandemic-control measures would gradually be rolled back, there was still no clear end in sight for the “dynamic zero” policy that aimed to keep Covid-19 infections to a minimum.

As late as November 15, the party mouthpiece People’s Daily published a commentary doubling down on “dynamic zero”. It said the Omicron variant of the coronavirus was more transmissible and that a spike in infections would inflict higher economic and social costs, given China’s limited medical resources.

A week later, resentment towards the restrictions sparked rare protests after a fire on November 24 killed 10 people in a residential compound in Urumqi that was allegedly under lockdown – something the authorities denied.

At protests in major cities including Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou the following weekend, people chanted slogans calling for an end to the zero-Covid strategy and held up sheets of blank paper – a symbol of their anger at restrictions on free speech. A small minority even called for regime change.

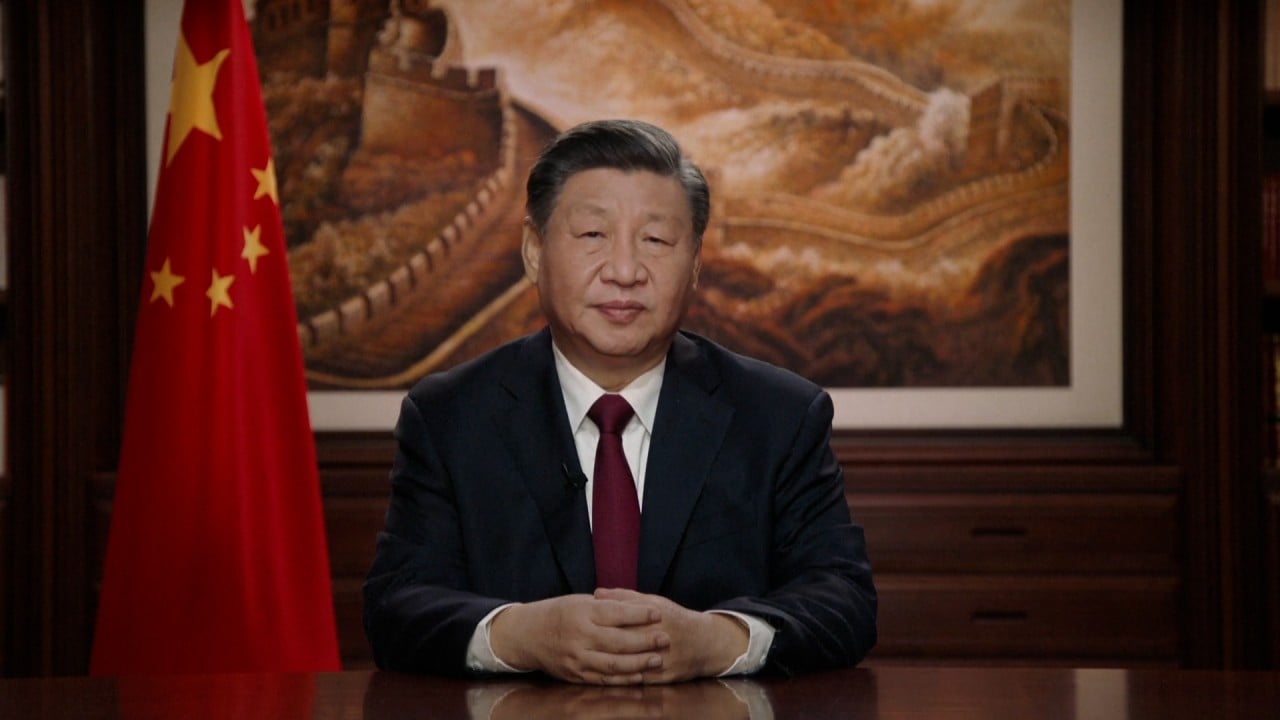

During a meeting with European Council President Charles Michel in Beijing in December, Xi acknowledged there had been frustrations about Beijing’s pandemic-control policies among a range of social groups, including students, a source said.

Xi added that the past three years “should’ve been the best years of their youth” and that a new Omicron subvariant was more “flu-like”.

At the end of the month, Xi also struck a conciliatory tone in his new year address to the nation, saying that “it’s normal there are different views from Chinese people”.

Why China’s lockdown protests pose an unprecedented challenge to Beijing

Beijing has never openly admitted the rare shows of public defiance were one of the main reasons for the abandonment of zero-Covid just days later, but Deng Yuwen, a former deputy editor of Study Times, the official newspaper of the Central Party School, said it was clear that the widespread protests had been a major political factor pushing the party’s leadership to speed up the relaxation of pandemic-control restrictions.

“It is very clear that the party’s leadership, especially Xi himself, heard the people’s demands,” said Deng, who is now an independent scholar and researcher at the China Strategic Analysis Centre in the United States. “Xi has subtly responded to it on many occasions and in speeches. That shows the level of concern.”

Deng said relaxing the restrictions had been Beijing’s best option to quell the protests.

“Demands from students and the public mainly focused on ending the strict zero-Covid policy; few of them actually targeted the regime and party leaders,” he said. “Responding to these demands of the vast majority of Chinese people by relaxing pandemic restrictions was the way to calm the boiling situation.”

‘Prepare for the worst’: China’s post-Covid recovery faces fresh challenges

A second conclusion that became obvious in November was that the economic cost of zero-Covid was unbearable. Economists at Japanese investment bank Nomura estimated that over a fifth of China’s gross domestic product was under lockdown that month, more than double the ratio in October.

Multiple sources said some leading cadres in major industrial powerhouses had reported the dire economic situation in their jurisdictions to Xi and other Politburo members.

A Beijing-based source said leading regional officials urging the party to rethink its zero-Covid policy included those from Shanghai and Guangdong province, two economic engines already facing pressure from the relocation of global supply chains, softening export markets and much weaker domestic demand following months of lockdowns.

“It might have been too late for the economy if zero-Covid were to continue for another quarter,” the source said, adding that many people had exhausted their savings during lockdowns.

By late October, Beijing had appointed former party propaganda chief Huang Kunming as party head of Guangdong and former Beijing mayor Chen Jining as party chief of Shanghai.

Huang is one of Xi’s most trusted loyalists, having served under Xi during his stints in the provinces of Fujian and Zhejiang. Chen is a protégé of party personnel chief Chen Xi.

In Guangdong’s provincial capital, Guangzhou, many migrant workers from Hubei province living in the city’s Haizhu district clashed with security forces, demanding the removal of lockdown barricades that prevented them from going to work.

The billions spent on mass testing and the construction of quarantine facilities also pushed many local governments to the edge of bankruptcy. Based on official data, China’s provincial governments faced a deficit over 13 trillion yuan (US$1.89 trillion) in the first 11 months of last year – 12 per cent more than for all of 2021.

In the second half of last year there was an increasing number of reports about local governments failing to pay coronavirus testing companies, those building makeshift hospitals, and the operators of quarantine hotels.

There were also reports, later denied, that Terry Gou, the founder of Foxconn – which employs hundreds of thousands of workers in electronics assembly plants across China – had written to the leadership to warn about the threat zero-Covid policies posed to China’s position in the global supply chain.

Foxconn’s main factory in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, faced a series of Covid-related problems late last year that highlighted the dilemma China faced in adopting a zero-tolerance approach to Covid-19 while seeking to maintain normal production. In October, thousands of Foxconn workers fled the factory due to the risk of Covid-19 infection, prompting Apple – a major customer – to issue a rare warning about reduced shipments of iPhone 14 models. The exodus was followed by violent clashes between workers and security forces over employee benefits at the end of November.

The political pressure from the widespread protests and economic pressure from regional governments pushed the leadership in Beijing to bring forward reopening, even though China was far from ready for it.

The chaos and confusion that unfolded across the country after the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions caught many by surprise. According to numerous eyewitness accounts, China’s public health system has come under tremendous pressure due to a nationwide tsunami of infections. Medical personnel and workers in mortuaries and crematories, many remaining at their posts despite being infected, have had to work around the clock to cope with the surge in infections and the number of bodies piling up. Many people have also complained about difficulties getting anti-fever medications, not to mention antiviral drugs such as Paxlovid that target the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19.

Another sign of China’s lack of preparedness was the low vaccination rate among the elderly, the most vulnerable group in the pandemic. Only 76.6 per cent of the over 36 million Chinese people aged 80 and above had received at least one shot when Beijing abandoned most Covid-19 controls in early December, and only 40 per cent had received a booster dose.

Winter was “not the best time” for reopening, said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, adding that it was usually the peak season for flu and other viruses affecting the respiratory system.

“With coronavirus, many public health experts are worried about the possibility of a tripledemic,” he said.

Wu said sub-zero temperatures in northern China meant people could not open their windows for fresh air, making it easier for infections to spread among family members.

Additional reporting by Jun Mai