Vancouver became a byword for money laundering, fuelled by Chinese cash. Can it flip the script?

- A new institute devoted to anti-corruption and anti-laundering efforts seeks to repair a reputation tainted by the ‘Vancouver model’ of Chinese money smuggling

- The project is the brainchild of Peter German, whose investigations into money laundering in British Columbia prompted outrage and a push for reforms

It is known as the “Vancouver model” – a criminal technique that turned the Canadian city into a byword for international money laundering.

The term, coined by Australian academic Professor John Langdale of Macquarie University in 2017, described a process in which launderers would simultaneously smuggle Chinese money to Canada in circumvention of Beijing’s cash export laws, while sending Canadian drug money back to gangsters’ bank accounts in China, all facilitated by British Columbia casinos, in a kind of criminal alchemy.

But now the backers of a new anti-corruption institute want to flip the script, and make Vancouver a model for anti-money-laundering and corruption compliance.

The Vancouver Anti-Corruption Institute (VACI), launched this month, is the brainchild of veteran crime investigator Dr Peter German.

The lanky and urbane former deputy commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) has been at the centre of BC’s money-laundering debate, as the author of two government-backed reports, which included lurid revelations involving cash-stuffed suitcases, luxury real estate, smuggled supercars, and a cast of Chinese gangsters, somnolent regulators and complicit realtors.

Killing shatters myth of ‘victimless’ China-Vancouver money laundering

“We’ve come to recognise that Vancouver is not pristine and perfect … There is an undercurrent of criminal activity and there is an international aspect to all of it,” said German in an interview ahead of VACI’s launch on December 9.

“The time is right for this institute,” added German, president of VACI’s advisory board.

Based at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and affiliated with the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme, VACI will research and make recommendations on anti-corruption and anti-money-laundering law reform, and is the only body of its kind in Canada.

It will operate as part of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform (ICCLR), a joint initiative of the federal Canadian and BC governments, UBC and Simon Fraser University, and the International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law.

Vancouver, with its laid-back cascadian lifestyle, might once have seemed an unlikely hub for a team of international crime fighters.

But the city’s real estate, gambling and luxury-car sectors have been roiled by German’s reports (commissioned by the BC Attorney-General’s office) on their infiltration by money launderers found funnelling money out of China and around the country’s US$50,000-per-person annual limit on cash exports.

German’s “Dirty Money” reports were released in 2018 and 2019, totalling more than 600 pages.

They included accounts of casino patrons buying chips with bricks of C$20 and C$50 notes packed in luggage and shopping bags; the “commonplace” use of straw buyers by money launderers and others to secretly purchase BC real estate; and “dismal” reporting of suspicious transactions by realtors and others.

Judges: CIBC bank supports clients who break China’s cash-export laws, to buy Vancouver homes

A public commission into money laundering in BC, headed by former judge Austin Cullen, was launched in 2019, largely as a result of the Dirty Money reports; it is expected to deliver recommendations in May 2022.

VACI, too, owes its existence to German’s probing, which he said inspired him to suggest the institute’s creation to the ICCLR.

Its backers include former Canadian prime minister Kim Campbell, who has been recruited to VACI’s advisory board.

At the institute’s launch, Campbell characterised money-laundering and corruption as “an insidious cancer” from which no country – including Canada – was immune.

German’s work had helped show this. But she was optimistic VACI could help turn the tide.

“What distinguishes Canada though is that I don’t think we have a culture that tolerates corruption,” said Campbell, also Canada’s former justice minister.

“Some countries, it’s so deeply rooted that people just shrug … But in Canada, people are outraged when they discover it. That’s a very wonderful thing, because when governments create the framework, there will be strong support for rooting it out.”

‘Rivers of money’

“Outrage” neatly captures the general response to German’s previous revelations.

His reports described illicit funds flowing into Vancouver from around the world, but with Chinese money a key component.

“Greater Vancouver has been at the confluence of the proceeds of criminal activity, large amounts of capital fleeing China and other countries, and a robust underground economy seeking to evade taxes,” wrote German in his second Dirty Money report. “These three rivers of money coalesce in Vancouver’s property market and in consumer goods.”

In his interview, German said that although international gangs tended to target their own ethnic communities, ethnicity itself had no particular bearing on criminality.

Yet Chinese money flows have dominated the conversation about money laundering in BC because of the sheer scale of China’s economy, Beijing’s cash-export restrictions, and consequent demand for illicit routes.

German said in his first report that although a range of international organised crime gangs had been present in BC, “of greatest interest to this review however, is organised crime which emanates from mainland China”.

Large cash payments for Vancouver taxes raised money-laundering concerns

Enter the so-called “Vancouver model”, highlighted by German’s reports, in which funds were effectively moved from China to Canada and vice versa, without any physical cash crossing a border, nor any international bank transfers occurring.

Launderers would instead pair people seeking to smuggle money out of China and into Canada with drug dealers looking to send money the other way.

The former would deposit funds into the gangsters’ Chinese bank accounts, and then fly to Vancouver, where they would take physical delivery of matching Canadian dollars in the form of drug money. This would be used to buy casino chips that would later be cashed out as a cheque – better to avoid triggering alarm bells when deposited in a Canadian bank account than bricks of cash.

Exactly how much money is involved in various Vancouver-centred laundering schemes remains unclear, although in 2020, the federal Criminal Intelligence Service estimated that C$45billion to C$113 billion (US$35billion to US$88 billion) was laundered in Canada per year.

To ask if [laundered money] has impacted housing prices in certain communities of the Lower Mainland [of BC] is really a rhetorical question. Of course, it has

Despite this, German’s reports said the impact of laundered funds on BC, particularly on the housing market, was apparent. “We make no attempt, nor have we been asked to quantify these money streams,” he wrote. “What is clear is that the total sum is large and to ask if it has impacted housing prices in certain communities of the Lower Mainland [of BC] is really a rhetorical question. Of course, it has.”

Vancouver is home to one of the world’s biggest Chinese diaspora communities – the satellite city of Richmond is the most ethnically Chinese city in the world outside Asia – making it a ripe target for Chinese gangs, said German in his interview.

Lawyer Christine Duhaime, a Canadian anti-money-laundering expert, said it remained a “controversial thing” to connect Chinese money flows to criminality. Part of the problem was that not everyone agreed whether money smuggled out of China should be treated as illicit by Canadian authorities and institutions.

Vancouver woman sues for US$200,000 lost trying to get money out of China

“From my perspective, if as the predicate offence money was exited from China illegally … that should be [treated as] proceeds of crime,” said Duhaime, who advises institutions on compliance and helps clients hunt down hidden and illicit assets around the world.

“Look at it from that perspective and I think there’s a large footprint that comes from China that impacts our Vancouver ecosystem when you look at money laundering.”

She said it was a “fallacy” to look at laundering through a purely Canadian lens that only asked whether the crime was committed in Canada.

Duhaime said she hoped VACI would help financial institutions beef up policies and procedures, “and to get us looking at this more internationally”.

For instance, Hong Kong banks took a far more rigorous approach than Canadian counterparts when it came to establishing the origins of Chinese funds, she said.

Laundering, she said, “impacts everyday life in Vancouver, every day. The moment you have proceeds of crime and corruption that have infiltrated an ecosystem it makes things less safe, it attracts more criminality, it drives prices up for things.”

Sometimes, violence has shadowed these practices.

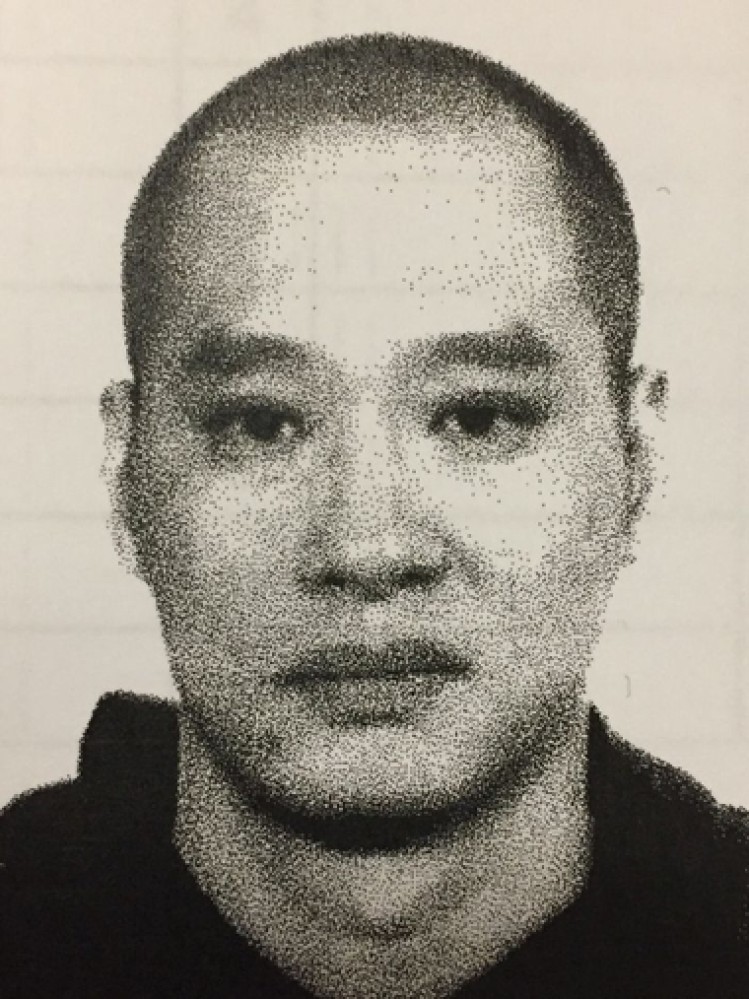

Zhu was suspected by police to have been involved in an operation that smuggled about C$220 million per year out of China and into Canada.

Richard Charles Reed, 23, has been charged with first-degree murder. A trial date has not been set, and no offence has been proven.

‘They are five steps ahead’

Some official moves have recently already been made against launderers, with BC casinos tightening practices, and the province launching a beneficial land owners’ registry, with a compliance deadline of November 30, 2022.

Duhaime applauded the registry, but warned that the battle against launderers looking to hide assets was likely never-ending.

“It’s a great move, but the second you do that, they are five steps ahead. They are figuring out other ways to do transactions and buy real estate in ways that are less transparent,” she said.

Investigation: BMW chases China car smugglers across Canada

Meanwhile, at this month’s Summit for Democracy in Washington, Canada’s federal government committed to a publicly accessible corporate beneficial ownership registry by 2025.

BC Attorney-General David Eby, who recruited German to write the Dirty Money reports, said in a speech at the launch of VACI that he hoped the institute would help reverse the “Vancouver model” perception of the city as tainted by money laundering, to represent one of “best practices”.

The initiative, he said, “represents a shift in culture in Vancouver”.

Alexandra Wrage, president and CEO of the worldwide anti-bribery business association TRACE International, also sits on the VACI advisory board.

She said in an interview at the VACI launch that Canada could not be complacent about money laundering and international crime “because having a good reputation as decent people is not a compliance programme. It’s not going to save you in shoddy markets.”

“What’s gone wrong in Vancouver? It’s almost a naivety about how easy it was to manipulate parts of the system,” said Wrage.

German, who was part of the same conversation, chimed in.

“‘Can’t happen here’,” he said. “But now our spidey senses have been alerted. It can happen here.”