Hooking up with Najib, Arroyo and Rajapaksa: the risks of China’s attachment to discredited leaders

Richard Heydarian writes that China risks triggering a backlash as it relies on cultivating ties with the ruling elite of beneficiary countries, many of whom tend to be corrupt

As America grapples with an erratic and distracted leadership, China has diligently forged ahead with its effort to consolidate its influence across the Asia-Pacific region.

According to a report by AidData, an American research institution, China has skilfully adopted a “multi-year, forward-leaning strategy”, which employs a diverse set of instruments, including “financial investments and official visits targeted towards a country’s elites, to mass-market appeals to citizens via Confucius Institutes, sister cities and information broadcasting”.

Regional leaders have been captivated by the relative ease with which China has offered capital and technology to even the most troubled, poverty-stricken regimes.

Down the road, however, China runs the risk of triggering a bottom-up backlash as it disproportionately relies on cultivating relations with the ruling elite of beneficiary countries, many of whom tend to be corrupt and increasingly unpopular.

Beijing’s charm-offensive strategy, beginning in the mid-1990s but reaching its zenith in the last decade, has multiple objectives.

First, it allows China to gain access to valuable markets and natural resources overseas. It also provides a key opportunity for China’s state-owned enterprises (SOE) to move up the value chain, test and improve their technologies and remain solvent and competitive amid a slowdown and overcapacity in domestic markets.

Is China eroding neighbours’ trust by buying political clout with foreign aid?

Through ambitious projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative, China also is in a position to connect its less developed hinterlands, where most of its restive ethnic minorities live, to lucrative markets in the Western portion of the Eurasian land mass.

China’s 21st century public diplomacy strategy has been primarily driven by infrastructure investments, constituting 95 per cent, or US$45.8 billion, of its total investments, so far.

China’s SOE have taken over more close to 90 per cent of all Chinese projects under the Belt and Road, while the remote areas of Xinjiang are expected to benefit from greater connectivity with Central, South and West Asian markets.

No other major power, with the exception of Japan, comes even close to China’s massive infrastructure footprint and ambition in the Asia-Pacific region.

The problem, however, is that China’s meteoric success in cultivating soft power across the region tends to inspire discontent and resentment among beneficiary nations.

It’s true that China has become more circumspect with its overseas investments, incorporating concerns about the long-term economic viability of its projects as well as the solvency of its beneficiaries.

Chinese investment winning hearts and minds in western Balkans

Yet Beijing-driven projects often tend to be funded by policy (rather than commercial) banks such as the China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

Overreliance on non-commercial banks may partly explain the upsurge in white elephant projects from Africa to Asia and Latin America over the years, and the massive debt build-up in small and relatively impoverished nations such as Laos and Sri Lanka.

Thanks to Chinese diplomatic support and largesse, many regional strongmen tend to become complacent, if not hubristic, thus sowing the seeds of their own destruction.

Moreover, China’s state-driven investments tend to be seen as narrow in focus, with comparatively less emphasis on humanitarian aid, grants and debt relief. This limits the extent of Chinese soft power, since the vast majority of the population doesn’t directly benefit.

Some even see them as predatory, since the projects are dominated by Chinese capital, technology and labour at the expense of their local counterparts; not to mention that Chinese loans carry interest rates that can be up to 10 times higher than those offered by Japan and other sovereign competitors.

An additional source of concern among some beneficiary countries is the perception that China seeks geopolitical and territorial concessions in exchange for investments, which aren’t charity but instead a ‘win-win’ for both sides. The upshot is a nationalistic backlash, as we have seen in the case of Vietnam in recent years.

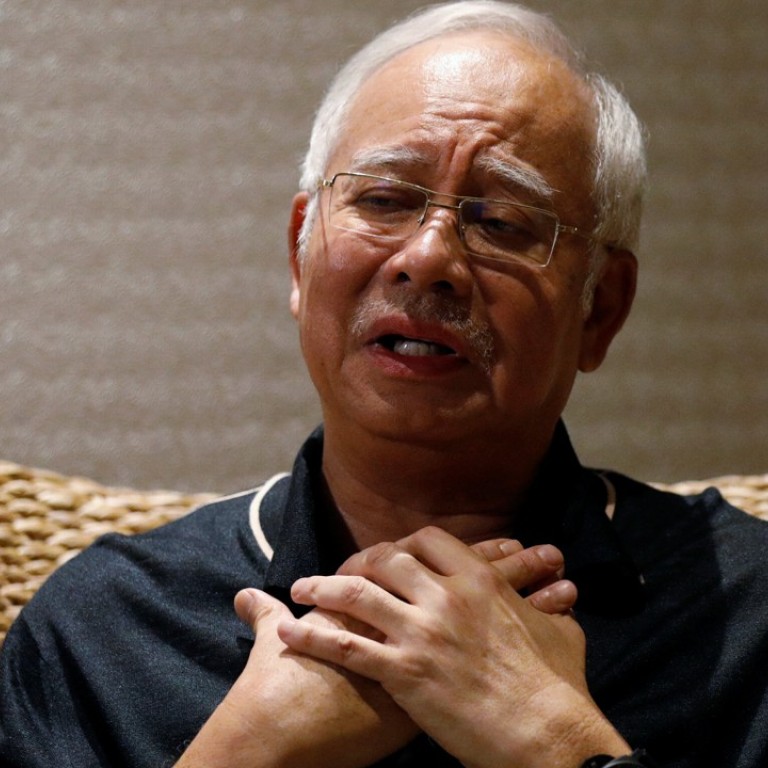

The primary source of bottom-up resentment, however, is Beijing’s tendency to form overly close relations with often corrupt and unpopular regimes. The shocking defeat of the Najib Razak coalition in the recent Malaysian elections is the most potent manifestation of this trend.

Though known for his pragmatism and anti-Western tirades, the newly restored Malaysian leader, Mahathir Mohammad, has been forced to adopt a tougher stance on Chinese investments precisely because of simmering domestic resentment.

Huge foreign aid programmes push China past Japan and India in global influence, report says

A few years earlier, in 2015, a similar electoral explosion took place in Sri Lanka and, before that, in 2010, in the Philippines, where maverick opposition leaders displaced entrenched leaders on a slogan of anti-corruption and a more independent stance towards China.

In all three cases, China was excessively attached to the discredited leadership of Najib (Malaysia), Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (the Philippines) and Mahinda Rajapaksa (Sri Lanka), who seemed strong on the surface but were extremely vulnerable to political backlash.

By associating with and investing in such leaders, China risked alienating the domestic population and being turned into a major target for the opposition.

In many ways, China could be repeating the same mistake in the case of the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, who remains popular today, but may face a different political landscape in years to come due to his divisive politics.

China launches mega aid agency in big shift from recipient to donor

Thanks to Chinese diplomatic support and largesse, many regional strongmen tend to become complacent, if not hubristic, thus sowing the seeds of their own destruction.

And therein lies the Achilles' heel of the Chinese charm offensive.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author