In Stalin’s footsteps in Georgia, from museums in Tbilisi and his birthplace that glorify the dictator to his personal bath, unheralded and unloved

- A visit to Stalin’s birthplace, Georgia, and his hometown, Gori, reveals a somewhat selective telling of the dictator’s early years and later achievements

- In Tbilisi visitors can see an underground printing press where the young Stalin may have worked, and in a spa town, Tskaltubo, his crumbling private bathroom

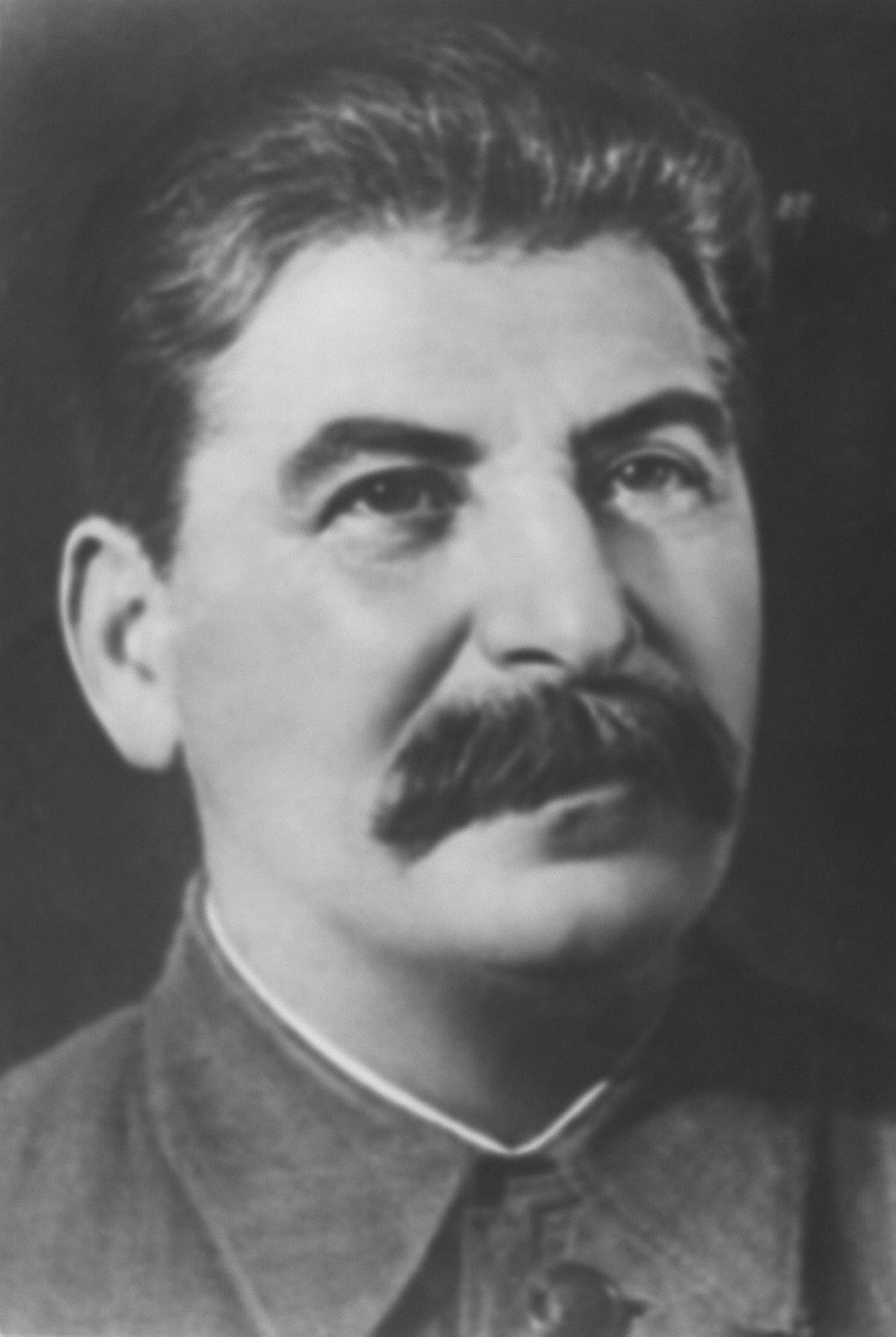

Georgia’s relationship with its most famous son is complicated, and nowhere more so than in his hometown of Gori, an hour’s drive northwest of the capital, Tbilisi.

For few outside the Caucasus can name any other Georgian, except perhaps for a handful of post-Soviet politicians who have caught the attention of the international press.

But even then Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, who ran the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953, is unrecognisable except under his Russian nom de guerre, Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin, or Joseph Stalin for short.

Certainly Gori lacks any other famous names, which makes it hard for that city to abandon Stalin despite the almost universal assessment of him as a brutal dictator and a murderer of millions.

Stalinist sympathisers live on even though the current Russian occupation of 20 per cent of Georgia’s territory is all too reminiscent of the invasion of 1921 that made the country an unwilling part of the Soviet Union for 70 years.

Stalin will never be forgotten, and the museum to his memory, on Gori’s Stalin Avenue, remains that city’s principal attraction.

Skiing in Georgia – fewer people and a fraction of the cost

But most visits to Georgia begin in Tbilisi, with its appealing mixture of elegant and dignified neoclassicism, post-Soviet modernity and ancient, frescoed churches.

All speak of the candidate European Union-member’s pro-European sensibility, as do EU flags flying outside public buildings and hanging from the balconies of private flats.

However, in the ramshackle warren of a low-rise suburb, large gates painted with the Soviet Union’s hammer-and-sickle emblem mark the entrance to the little-visited but fascinating Underground Printing House Museum, which is effectively a shrine to Stalin.

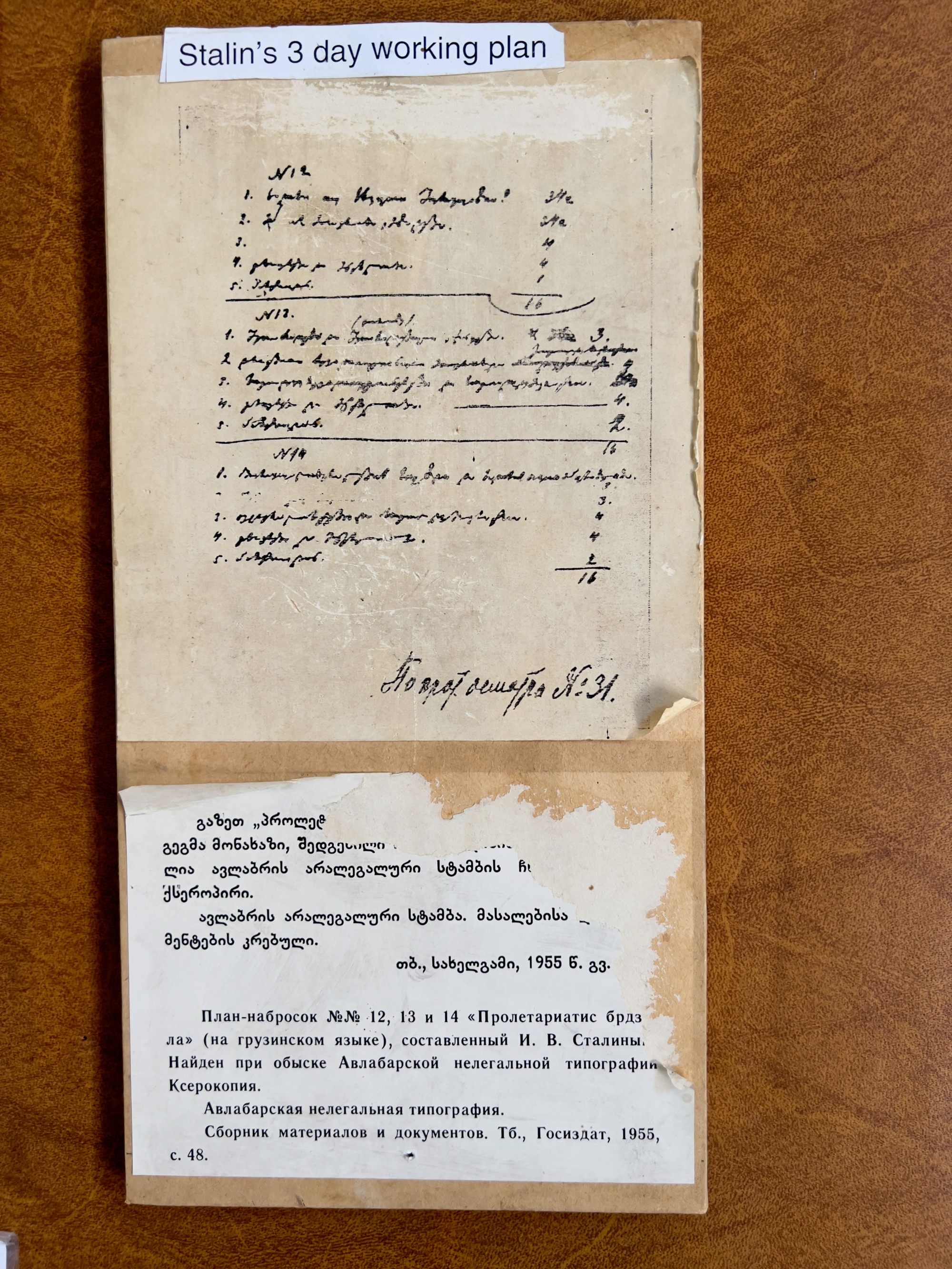

According to a slightly confused account in the museum’s English handout, in 1893, revolutionaries obtained a printing press in Augsburg, Germany, then had it dismantled and secretly shipped to Tbilisi piece by piece.

Each part was lowered down a functioning well, carried along a short horizontal passage and hoisted up another, dry shaft to a hidden chamber beneath a small house in what was then still open countryside, although this wasn’t built until 1903.

It is claimed that the young Stalin, whose official birth year is given as 1879 but was, in fact, a year earlier, worked here between 1903 and 1906. He and his comrades produced anti-tsarist and pro-communist propaganda in Armenian, Georgian and Russian, of a quality that attracted the attention of Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin himself, then exiled in Geneva, Switzerland.

Stalin’s biographer Simon Sebag Montefiore has his subject partly in Siberian exile during this period, and travelling extensively after his release, including to Finland for his first meeting with Lenin.

He was also, by his own later claim, organising peasant revolts elsewhere. None of these discrepancies are allowed to trouble the telling of a good tale.

Eventually the revolutionaries’ location was given away, although the hidden printers, tipped off, fled before the tsarist police arrived. These officers, despite numbering 150, were initially unable to discover the hidden press, but in the end they removed it and blew up the house.

It was reconstructed in 1937, and perhaps the story of Stalin’s heroic involvement was assembled at the same time. But whatever the truth, the trip down a rusty spiral staircase in a dank shaft is still redolent of danger and derring-do.

An ancient attendant, staunchly Stalinist to this day, invites visitors to bend down and enter the horizontal passage to get a view of the original well down which the conspiracists descended. And to the squeals of complaining metal he demonstrates the operation of the even more ancient hand-cranked printing press, also now reconstructed.

At ground level, forlorn rooms contain a reproduction of Stalin’s living quarters, and displays include a copy of a letter from Lenin to Stalin, handwritten notes by Stalin himself, and a copy of the first issue of Soviet Communism’s official organ, Pravda (“Truth”), although this was published in Moscow, and Stalin didn’t join the editorial board until 1917.

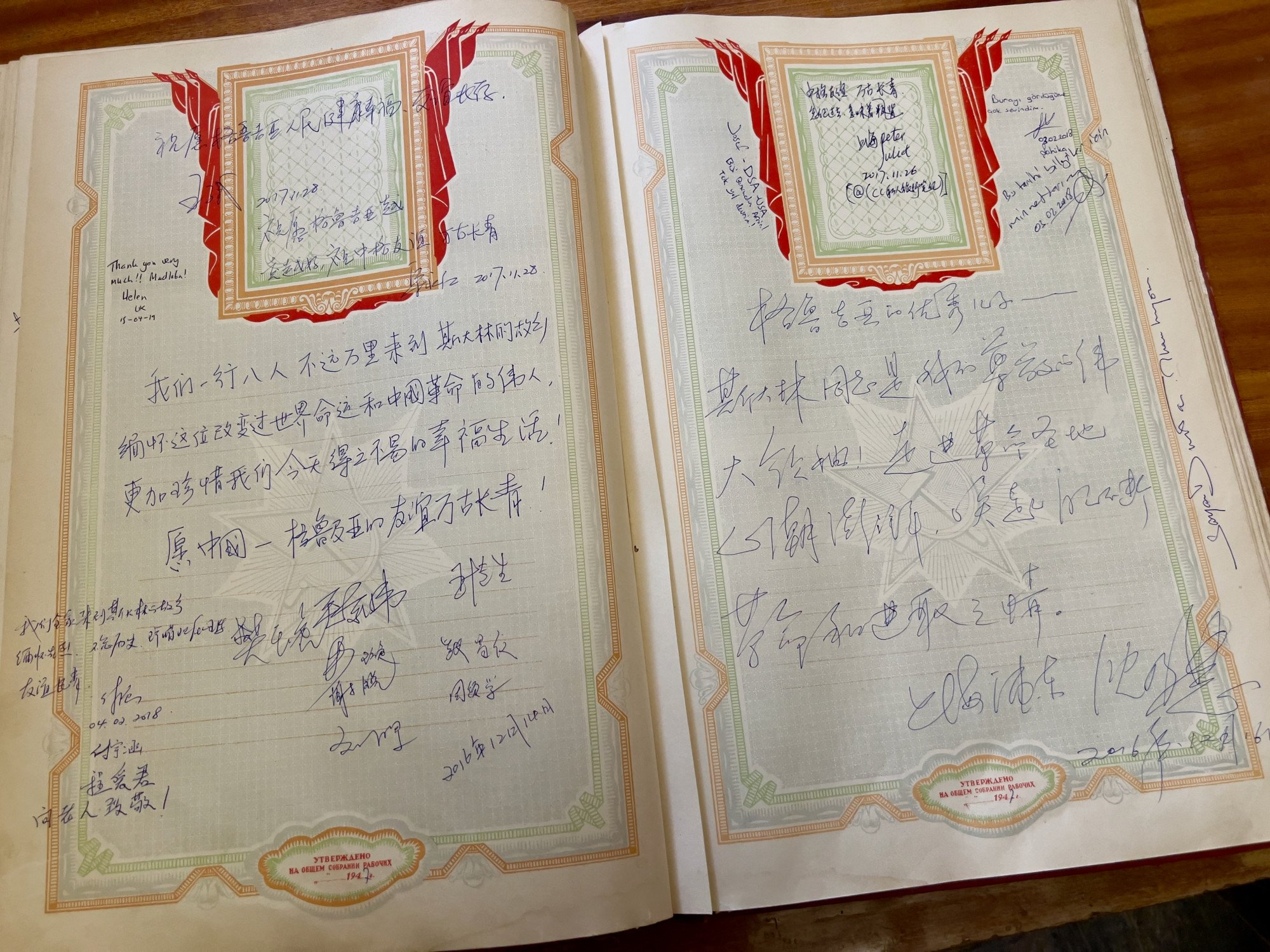

Whatever the truth of the museum’s narrative, staff claim that the story remains part of the Chinese school syllabus, and the visitors’ book is certainly scattered with Chinese names and their comments in both Chinese and English: “Long live communist [sic],” says one. “Long live China-Georgia friendship.”

At the Stalin State Museum in Gori, there’s greater grandeur. The battered cottage that was the childhood home of shoemaker’s son Stalin until 1883, and home to his memorial museum from 1937, is now dwarfed by the neoclassical temple built over it.

Behind is an elegant mansion, erected after Stalin’s death, in 1957, to house a more extensive account of the dictator’s life.

Inside there’s a real whiff of the Soviet era in the red carpet running up a broad marble staircase beneath a substantial chandelier, leading directly to a bust of Stalin, and then to a series of large, high-ceilinged salons that present a purportedly forensic but, in fact, unscientifically selective account of the man.

The museum’s exhibits run to about 47,000 items and displays begin with a watercolour of Stalin as a child, information about his teachers and his 1894 application letter to the rector of Tiflis (Tbilisi) Orthodox Seminary.

They continue with busts, portraits, copies of decrees, texts of speeches and historic photographs. Then accounts of military campaigns both domestic and foreign, displays of possessions including an ashtray and a musquash coat, and birthday gifts from foreign powers.

The Holodomor, the man-made famine of 1932-33 in which more than 3 million Ukrainians perished, is not mentioned; nor is the Great Terror (1936-38), in which Stalin’s critics were eliminated, with perhaps 750,000 murdered and a million exiled to Siberia.

The only grudgingly dissonant notes in this symphony of sycophancy are a photograph of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, an agreement between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany to divide up Central and Eastern Europe ahead of World War II, and a small selection of portraits of Georgian artists and intellectuals whom Stalin had persecuted or had murdered.

The name Stalin is derived from the Russian for “steel”, and the man appears to have shown his homeland no special softness. The number of his victims here was disproportionately large compared to the size of its population.

“The museum has been mostly frozen in time since 1979,” says one staff member, except, he points out, for one recently added display tucked away beneath the grand main staircase. This most independent visitors overlook, and tour guides ignore altogether.

Even here – among photographs of railway construction and firing squads – criticism is expressed more in generalities, and mentioned alongside the Soviet Union’s rapid industrialisation under Stalin. There’s rather more space given to the atrocities of recent Russian invasions of Georgia.

But back out in more cheerful sunlight there’s charm in wandering along the corridor of Stalin’s personal railway carriage, and more charm still three hours to the west, in Tskaltubo.

At its peak, the spa town was served by four trains a day from Moscow, a journey that took two days. It grew to support a number of sanatoriums in both traditional and Sputnik-era modernist styles, as well as comfortable hotels for the apparatchiks and more modest accommodation for the proletariat.

Business collapsed with the end of the Soviet Union and Georgian independence in April 1991, although some of Tskaltubo’s abandoned buildings were reopened to house refugees from the 1992 Russian occupation of Abkhazia, in Georgia’s northwest. Some refugees are still resident today.

But now private enterprise has been invited in, there’s some revival of business, and various buildings are shrouded in scaffolding, while others, such as Sanatorium No 6, have already been renovated.

A frieze on the portico, in high relief, shows Stalin accepting flowers from a peasant woman holding a child, with other happy workers and peasants behind.

Here the big man bathed, but there are no signs.

“Go round to the right,” says a receptionist. “The nurse will show you.”

Across a columned entrance hall of a certain wedding-cake grandeur, along a chair-lined passage and through a door, the building’s shiny smartness is suddenly replaced by decay, as if the refurbishment abruptly ran out of budget.

Substantial dust-covered leather armchairs sag in an anteroom, through which steps lead down into a large sunken bath, brightly lit by high arched windows and floored with a mosaic of sea creatures that seem more appropriate to a children’s paddling pool than to the downtime of a dictator.

As with all Stalin-related narratives the truth isn’t clear, but it is thought that he perhaps wallowed here in 1931 and again in 1951. Now unheralded and unloved, tiles beginning to drop from the walls, the bath may eventually be restored to its former glory, or may be refitted for other purposes. The staff are unable to say.

Sidelined as Stalin may be here, he is doing better than at Batumi, now a major resort town, two hours southwest on the Black Sea coast, but also once a base for his youthful campaigning activities. Here maps cannot even accurately place his old flat, despite the fact it is, according to numerous sources, preserved as a shrine.

When finally found among older housing and new construction, there’s no entry, public access having been “abolished” in 2013, according to Georgian television, for lack of interest.