Oh the irony: Scottish soldiers defending Hong Kong in 1941 used tunnels whose builders named them after roads in London

- Oxford Street, Charing Cross and Regent Street were among the names given to the defensive tunnels of Hong Kong’s Shing Mun Redoubt by their builders

- Yet, when the Japanese invasion came, London-area troops of the Middlesex Regiment defended Hong Kong Island, with Scots alien to the UK capital in the tunnels

Strung out along several ridges above and around the Upper and Lower Shing Mun reservoirs, in the central New Territories, the underground defensive complex known as the Shing Mun Redoubt is one of Hong Kong’s most extensive – yet sadly underused – heritage resources.

Built in 1936-37, and until now mostly well preserved, general public awareness of its existence – along with increased vandalism – has steadily developed, after several decades of benign neglect.

First noticeable after 2014’s protests, slogans from various sides of the ideological spectrum are scrawled on walls, then blotted out by their political opponents with fresh paint or dissolved with solvents, and soon afterwards replaced by fresh epithets.

In the process, original paintwork and concrete rendering, or extant wartime evidence such as blast holes or shrapnel damage, are further compromised.

The Shing Mun Redoubt’s overall layout – tunnel systems are named after major London roads – makes intuitive sense to anyone familiar with the West End.

A long, mostly straight thoroughfare, Oxford Street runs “across the top”, then connects to Regent Street, which, in turn, eventually reaches Piccadilly.

From that junction, Shaftesbury Avenue – with Haymarket just below – arrives at Charing Cross; from there, a few steps lead to the Strand Palace Hotel.

A coded reference to that pre-war landmark has an inner logic comprehensible to any 1930s Cockney.

Just imagine – it is late Saturday evening, and there’s a right royal old donnybrook kicking off somewhere down the road and the top brass need to be found – and fast! But where are they likely to be found at that time of night?

Where else, but just up the way in the magnificent Strand Palace Hotel, all glittering art deco lights and modern conveniences. And if the officers happen not to be there, then someone propping up the bar will know their whereabouts.

Unfortunately, this logic only made strategic sense if the unit that helped lay out the Shing Mun defence system, and then trained there extensively for the next couple of years, were ultimately destined to fight there.

‘I have shot Buzz’: British officer in the Battle of Hong Kong

Retrained from a light infantry battalion to a medium-machine gun battalion in late 1939, with a different operational role in the event of hostilities breaking out in the Far East, the “Die-Hards” (as the Middlesex Regiment were known) were deployed, for the most part, in the extensive series of fixed machine-gun positions – known as pillboxes because of their square, box-like shape – girding the northern shore and southern coastline of Hong Kong Island.

While some guarded approaches to ferry piers and dockyards, pillboxes mostly provided arcs of fire along shorelines below fixed, mostly cliffside artillery emplacements at Pak Sha Wan, Cape Collinson, Cape D’Aguilar, Stanley, Chung Hom Kok, Brick Hill and Mount Davis.

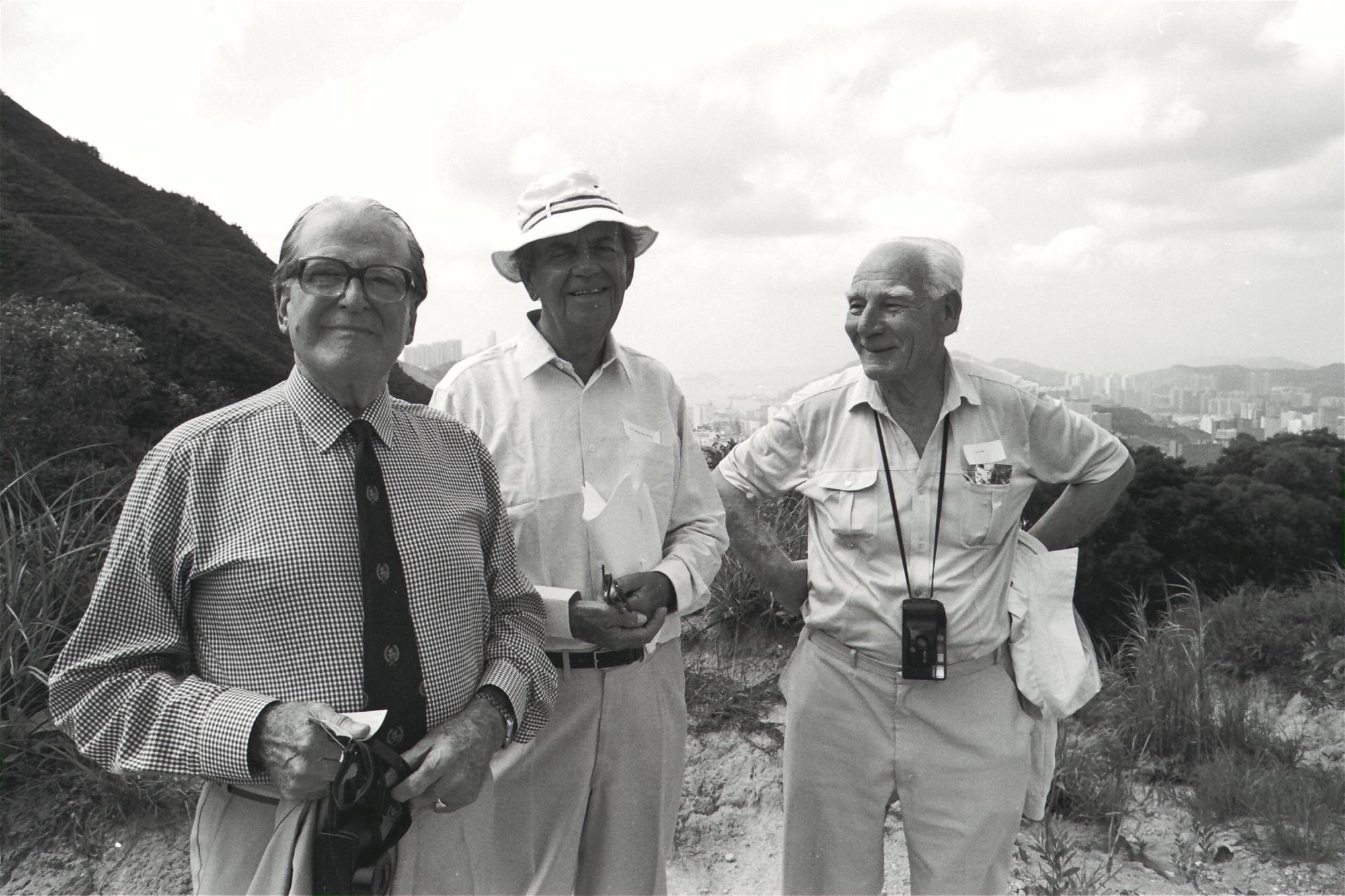

All this was carefully explained to me nearly 30 years ago by Captain (later Colonel) Anthony “Tony” Hewitt, who, as Adjutant of the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment when the Japanese invaded, was the man who tied the white flag on the pole when Hong Kong was surrendered on Christmas afternoon 1941.

Tunnels and emplacements named after Princes Street, Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh Castle, Waverley Station, the Royal Mile, Arthur’s Seat, the North British Hotel and other Edinburgh landmarks would have made more sense to them than London thoroughfares.