How advent of the telegraph made Hong Kong a global communications hub – no more 6-week waits for mail from Europe to arrive

- People today can’t bear being deprived of mobile phone networking for even a few hours, yet mail from Europe to Hong Kong used to take four months to arrive

- The Suez Canal and steamships reduced the mail delivery time to six weeks, but it was the laying of international telegraphic cables that was transformative

Instant global communications across a variety of platforms are regarded as one of modern life’s most essential amenities. As many of those deprived of their mobile phone for a few hours would attest, jittery withdrawal symptoms from being outside immediately accessible interpersonal contact can be profoundly unsettling.

To many younger people, instant communications are considered so normal that a world in which such communications took days, if not weeks or months, is almost impossible to envision.

Some historical perspective into Hong Kong’s pioneering connections to rapid changes in international connectivity provides additional insight.

When physical mail was transported across the world, inevitably letters took time to arrive. Before the Suez Canal opened, in 1869, along with the advent of reliable steam-driven vessels, mail from Europe to the Far East took three to four months to arrive, via the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The new route reduced this time to around six weeks.

In tandem, scientific and medical innovations, such as anaesthetics and painkillers, antiseptics and disinfectants, potable water and artificial ice, all combined to make life in the tropics healthier than during any previous period in human history, and exponentially increased demand for faster flows of information.

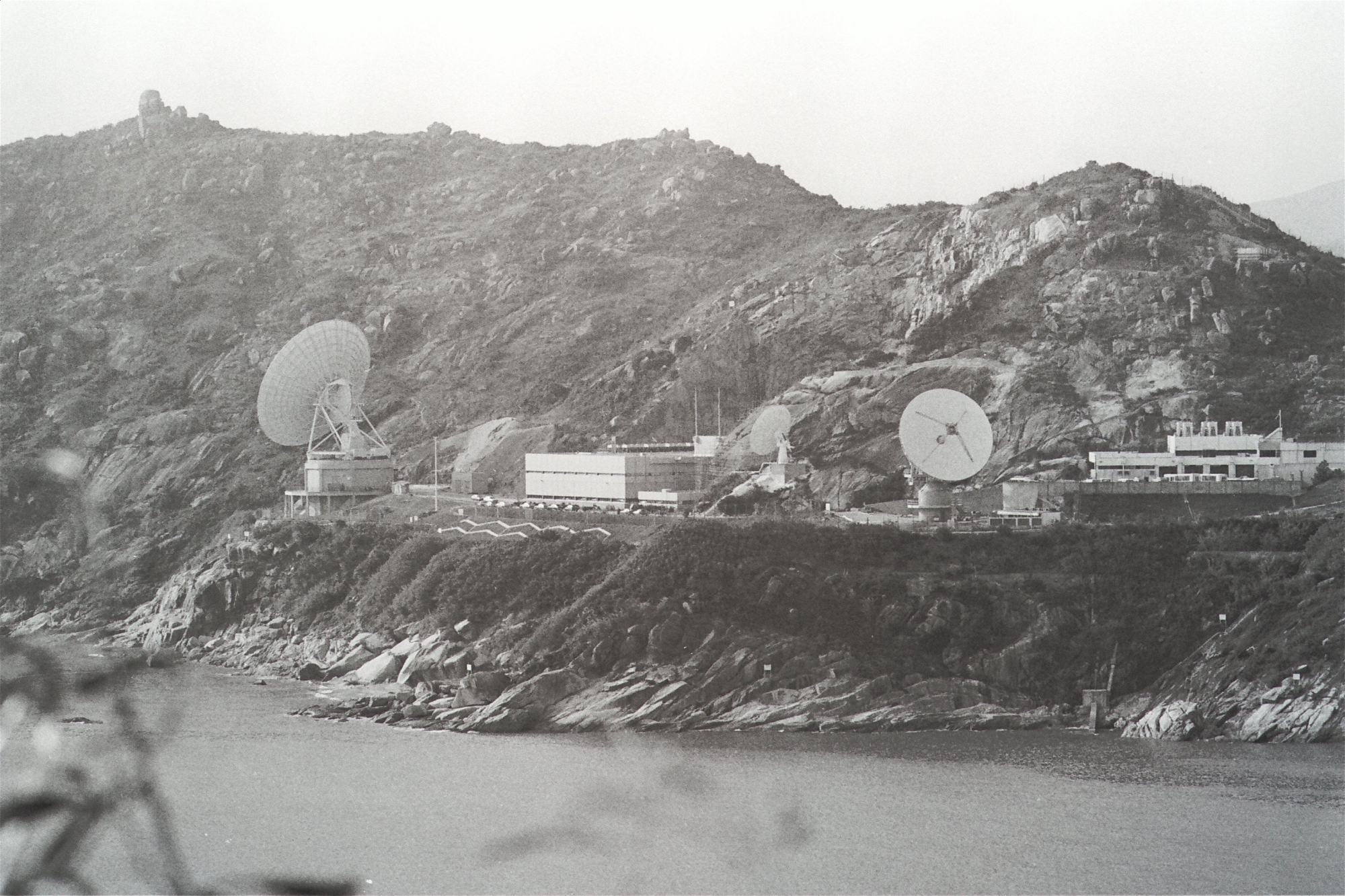

Overland and submarine telegraphic cables laid in the following decades completely changed how people lived – and how business was conducted.

Telegraphic messages from the other side of the world – with allowances for short delays in re-transmission from intermediate receiving stations – were as close to real-time as it was possible to get. Return messages were typically received within 24 hours – often less.

When the fastest previous mail turnarounds were about 12 weeks, this innovation was considered nothing short of miraculous, and led to rapid surges in economic activity. Before their introduction, business decisions were based on best guesses.

With cable communication, real-time assessments reflected actual global market conditions. Emergent events required immediate responses, and Hong Kong – a global communications hub long before such terms existed – was ideally placed to take advantage of this new trend.

How vanishing of Hong Kong’s letter writers reflects city’s biggest success

These new information-transfer systems, which swiftly made physical communication unnecessary, inadvertently generated a raft of new problems, data security being the most critical.

General international communications – such as occasional personal telegrams – were sent to the local telegraph office, along with a delivery address for a physical copy of the message on a Cable & Wireless letterhead, or that of the local equivalent company.

Complete privacy was impossible, and cryptic messages were sometimes deployed. Even though telegraph company employees were required to be discreet, rewards could be offered for sensitive commercial or other information.

Personalised telegraphic addresses were formulated to ensure some degree of privacy. Much like present-day email addresses, telegraphic addresses ranged from the prosaic to the bizarre, by way of the merely memorable.

Unlike email, which is virtually free, perennially high international cable charges meant that quirky personalised telegraphic addresses were a hallmark of the wealthy.

Long-ago business directories contain numerous examples; in the 1951 edition of the Hong Kong Dollar Directory – to cite just two – “Wearwarm” was the telegraphic address for the Hong Kong Cotton Weaving Manufacturers’ Association, and the Hongkong Engineering and Construction Company used “Ferroconco.”

By the 1930s, telegraphic messages were increasingly sent by radio, especially in places – such as inland China – that had limited (or non-existent) landline communications.

In China, the National Radio Administration controlled – and monitored – all internal and external wireless communications.

At a time when the Nationalist government’s hold on power remained tenuous, and most senior provincial officials had been warlords only a decade or so earlier, the government shrewdly realised that while potential insurgents might cut telegraph cables without much difficulty, they cannot sever the air.