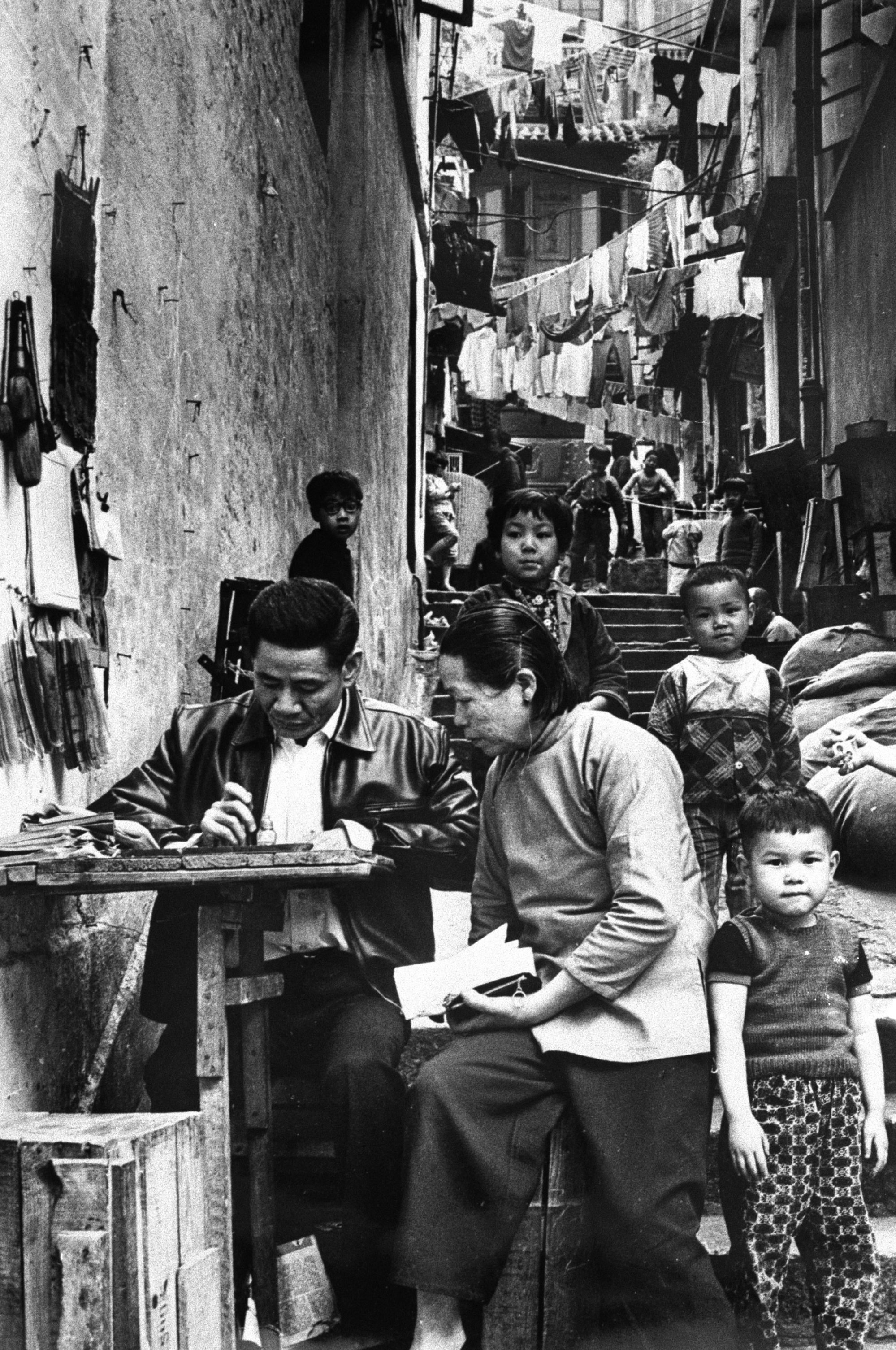

Why ending illiteracy among its Chinese population is Hong Kong’s greatest social achievement

- A century ago, Hong Kong’s Chinese population was almost completely illiterate, and used professional letter writers for their correspondence needs

- These entrepreneurs, with their folding tables and sometimes typewriters, slowly vanished from the streets – a reflection of today’s near-universal literacy

Probably the greatest single achievement any society can attain, beyond ensuring that a country’s people are free from famine, is universal literacy.

That China has accomplished this feat within a century, and from a starting point of near-universal illiteracy, when the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, is extraordinary.

Both Nationalist and Communist regimes must share credit – without this most basic building block of human attainment, no other national development would have been possible.

In 1923, an official report estimated that more than 90 per cent of Hong Kong’s ethnic Chinese population were illiterate. Even among the wealthy, female literacy was unusual – and frequently discouraged for reasons of patriarchal control over women.

In any case, much of urban Hong Kong’s Chinese population were rural sojourners impelled by poverty to relocate from further afield in the Pearl River Delta.

Illiteracy, however, did not eliminate occasional correspondence needs. When a death, birth, marriage, change of address, or some other critical life event occurred, word had to be sent home – and the same was true in reverse.

100 years of gas street lamps in Hong Kong, and the relics that live on

True to entrepreneurial form, an ingenious Chinese substitute arose – the professional letter writer.

Seated at a small folding table under the covered pavement arcade of a side street, the scribe would provide covering letters for remittances back to the heung ha (“home village”), read letters received by customers for a fee, fill in forms and draft petitions, if required.

Professional letter writers were typically men with some education who, for whatever reasons, had been unable to progress further in their studies.

Many were only marginally more literate than their customers, but with the age-old Chinese reverence for the lettered, these scribes were accorded the formal courtesies and due respect shown to scholars by their customers.

Why Hong Kong’s ceilings used to be much higher than they are now

Some scribes invested in typewriters; official forms thus submitted looked more efficient and impressive. And, of course, typed correspondence cost more.

Privacy was impossible, and the professional letter writer was often the first shoulder that was cried upon when bad news came from far away.

A Hong Kong amateur historian dead 35 years but whose work still resonates

Until recent years, several still operated in older districts such as Wan Chai and Yau Ma Tei a few mornings or afternoons a week, more often as a service to steadily dwindling numbers of long-term clients than as any remunerative business for the scribe himself.

The disappearance of professional letter writers from contemporary Hong Kong – much like the departure of reeking night-soil buckets from tenement stair landings and the nocturnal visits of their black-clad collectors – is a success story that should be widely celebrated.

Near-universal literacy remains post-war Hong Kong’s greatest single societal achievement. Despite obvious deficiencies in the local education system, Hong Kong’s people can read – the first necessary step towards making up their own minds about the state of the world around them.

Few other places have done so well, in such a short time, with limited resources; a magnificent, praiseworthy “good Hong Kong story” of achievement against significant odds, and eminently worthy of celebration.