How Hong Kong’s post-war initiative to support struggling farmers helped Gurkhas returning to Nepal – where it had a lasting impact

- Farmers on the breadline in post-war Hong Kong were helped by the Kadoorie brothers’ agricultural aid initiative that retrained them and gave financial support

- The scheme was extended to help Gurkha soldiers returning to Nepal readjust to agriculture, and gave small disbursements that proved vital to remote communities

Fresh water provision was a perennial Hong Kong problem from its mid-19th century urban beginnings; critical shortages were commonplace.

The Shing Mun Reservoir scheme in the New Territories, opened in 1935, provided essential supplies for urban areas, but at the expense of New Territories livelihoods, which changed forever within a few years.

Streams formerly channelled towards rice-field irrigation were diverted to the reservoir, leaving many farms waterless. Where irrigation was possible, and soils were suitable, some former rice fields became market gardens, with produce grown for sale in Hong Kong and Kowloon.

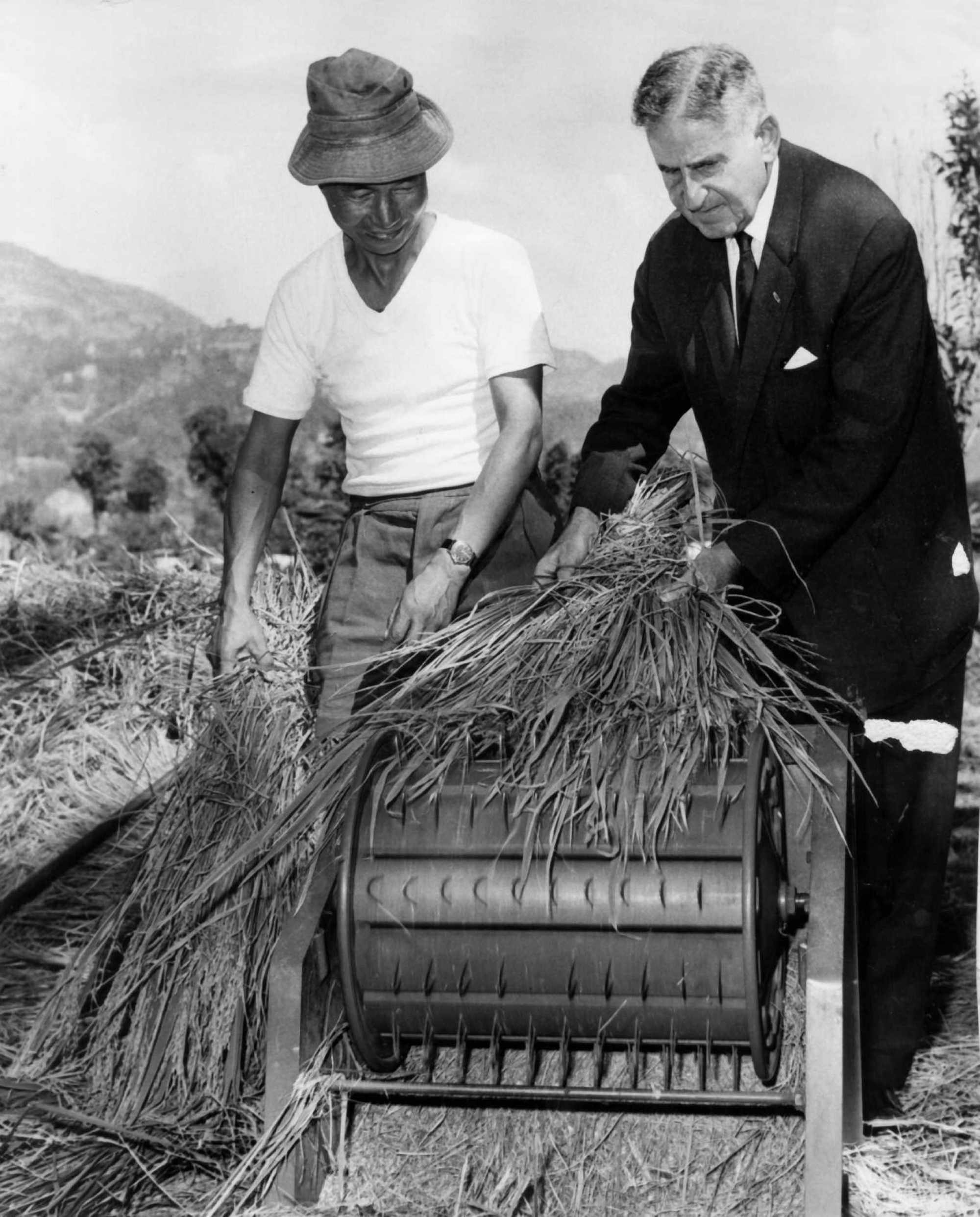

More efficient vegetable farming methods and animal husbandry skills – particularly for chickens and pigs – were essential. Farmers who had grown rice for generations had to acquire completely new skill sets.

The Hong Kong government, through the New Territories District Administration, provided agricultural extension officers and experimental farms, where new crop varieties could be tested before widespread introduction.

The livelihoods that this timely assistance provided are warmly recalled.

Often a few days’ walk or more into Nepal’s mountain ridges and remote valleys, these hamlets lived on subsistence agriculture; ironclad (if meagre) military pensions were vital additional support for many families. Agricultural resettlement courses were tailored to the requirements of former servicemen.

Fact-finding “welfare treks” visited remote mountain villages to determine requirements first-hand. Small practical disbursements, such as sacks of cement, might help improve pathways, or enable weir construction on mountain streams, providing significantly improved irrigation; corrugated-iron sheeting helped roof a village schoolhouse.

Decades before the corporate social responsibility buzzword was coined, these microgrant disbursements made a lasting difference throughout Nepal.

Gurkha wives, in particular, were even less interested in returning to lives of back-breaking drudgery, carrying water long distances by bucket, and so on. Driving and mechanical courses, and other practical skill sets also enabled further overseas employment possibilities.

As these more popular alternatives were introduced in the early ’90s, the once-popular agricultural extension courses conducted at Lam Tsuen, close to the New Territories military bases and married quarters where many Gurkha families had spent large tracts of their lives, were gradually discontinued.