Why there is no universal sign language, and how the embrace of non-verbal communication is a welcome sign of the times

Sign languages are different around the world, and even exhibit regional variants, but they are increasingly being accepted as official means of communication

September 23 is the International Day of Sign Languages, but most of us know little about the means of non-verbal communication that has proven invaluable for the deaf and hard of hearing around the world. Perhaps surprisingly, there is not just one sign language, and different countries have different systems, often with regional variants. Like spoken languages, they developed among groups of people interacting with each other.

Many of the world’s major sign languages (exceptions include Chinese, Japanese, Indo-Pakistani and Levantine Arabic) can be traced to two origins. British Sign Language (BSL) spread to the Commonwealth with 19th-century British settlers; a sign language within England’s deaf communities was noted from 1570. BSL, New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) and Australian Sign Language (Auslan) share many similarities and comprise the BANZSL language family.

What Buddhist monks and discreet dealings have in common: hand signals

French Sign Language, meanwhile, established in the late 1700s, is usually identified as the root of American Sign Language (ASL), which developed in the 19th century, and of Quebec and many European sign languages. In the 1970s, with contact between deaf users of different sign languages, a pidgin – International Sign – was developed.

Sign languages evolve within deaf communities and neither mirror nor are dependent on the surrounding spoken languages; they are fully fledged natural languages with intricate grammatical organisation of their own. Auslan word order is different from English; and ASL and BSL differ significantly, more so than American and British English.

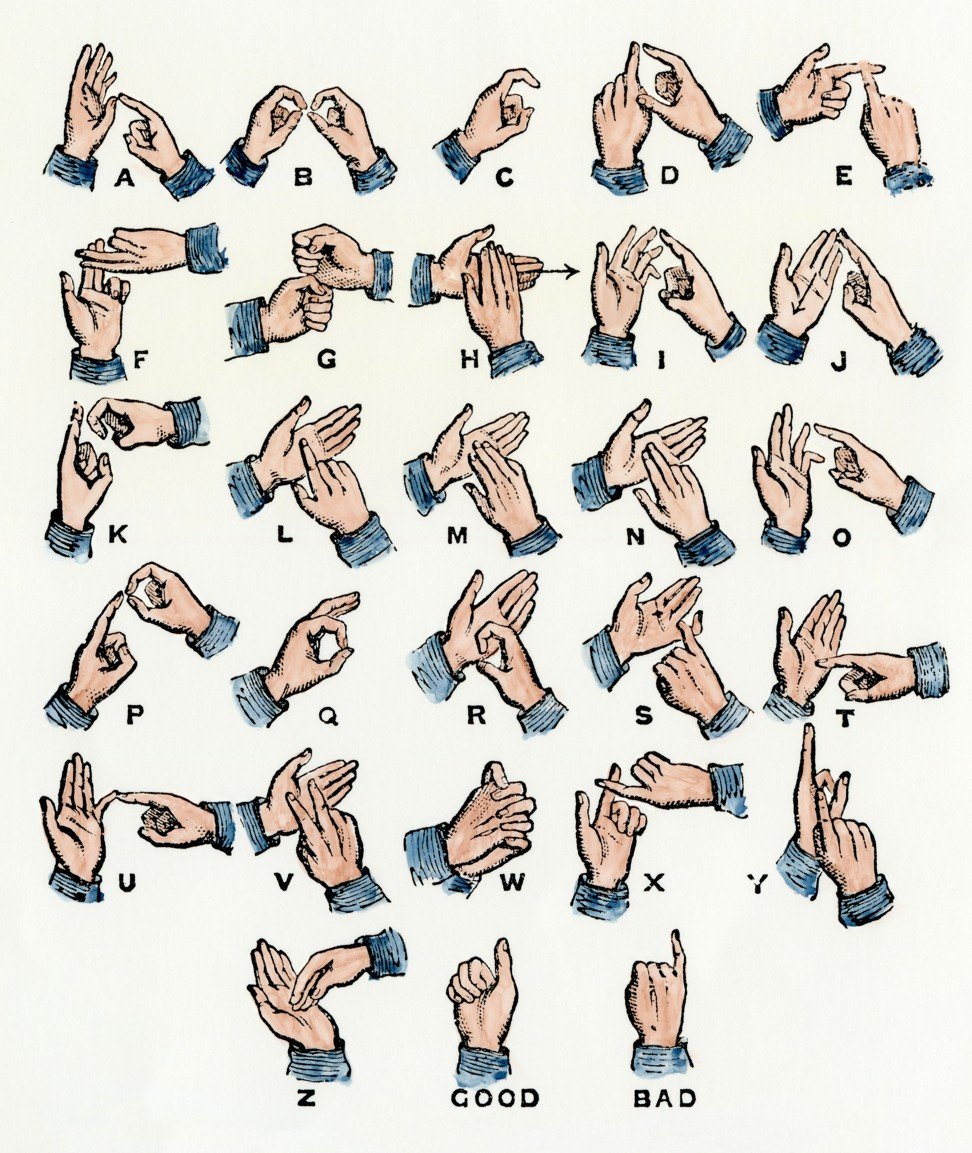

While sign languages are usually associated with hand shapes, the rules for well-formed sentences also include eyebrow position, eye position, hand motions and where signs occur in relation to the body. Facial expressions also play a fundamental role, notating rhythm and tone.

Sign languages are acquired like spoken languages; babies with signing caretakers pick up signing through natural interaction. Babies start “babbling” with their hands, then, when starting to produce words, substitute easier hand shapes for complex ones, later stringing signs together for sentences.

Sign languages evolve like all languages, borrowing signs from other languages, developing new signs to meet new needs.

From a time in the mid-20th century when sign languages were discouraged in schools, today there is increased support for the deaf. Auslan was recognised by the Australian government as a community language other than English in 1987, and, among others, NZSL and Korean and Papua New Guinea sign languages became official languages in 2006 and 2015, respectively.