- The Saudi Pro League’s big spending has drawn inevitable comparisons to the doomed Chinese Super League, but will it learn from China’s mistakes?

It’s been barely five years since West Ham United footballer Marko Arnautovic kicked up a dreadful fuss to try and force a transfer to Chinese Super League (CSL) club Guangzhou Evergrande.

Take with a pinch of salt what Arnautovic’s brother and agent, Danijel, said about a desire to “win titles in China”. The forward was 29 years old and reportedly being offered £280,000 (US$360,000) per week to take his capricious talent to Guangzhou.

It was January 2019 and the CSL and its clubs were still trying to paint a picture of a league committed to luring the world’s best and most high-profile footballers.

But the reality was rather different, a far cry from April 2016, when the Chinese Football Association declared in a report that it intended to become a “world football superpower” by 2050.

This was emboldened by President Xi Jinping’s publicly stated ambition for China to not only qualify for a World Cup, something they have previously managed only once, in 2002, but to eventually host and win the quadrennial tournament.

The end game imagined by Xi, when he encouraged Chinese football to think big, was a national team capable of going toe-to-toe with the heavyweights: Brazil, France, Spain, England and current world champions Argentina.

Phase one of this mission involved throwing enormous sums of money at established stars, with the aim of convincing them to play in China and, consequently, increase the competitiveness and profile of the CSL.

Suddenly, a league that was formed only in 2004, in a country where football turned professional as recently as 1994, was outspending other, traditionally elite domestic sports.

Football has two transfer windows each year, one in the winter, another during summer, when clubs are permitted to buy and sell players. In the January 2017 window, Chinese clubs lavished £331 million on players, dwarfing the £215 million spent by teams from the financially dominant English Premier League.

Arnautovic knew what he stood to earn from Guangzhou, and when West Ham manager Manuel Pellegrini excluded the Austrian from his squad during the transfer squabble, he pointedly said the player’s “head was on another issue”.

West Ham ultimately refused to be railroaded into a sale, and Arnautovic signed a new contract. But he had dropped a lit match on his relationship with the club’s supporters, and the uneasy truce lasted only six months before Arnautovic got his Chinese wish, moving to Shanghai SIPG on a weekly wage of around £200,000 in July 2019.

He would stay just two years, and remains the last player of any profile to stridently seek a move to China.

Guangzhou Evergrande, Arnautovic’s original suitors, was founded on enormous investment from property developer Evergrande, which bought the club in 2010, and began construction on a US$1.86 billion, 100,000-capacity stadium in April 2020. Work stalled 16 months later, with Evergrande sinking under more than US$300 billion of debt. The project was cancelled in 2022.

The squad currently sit 12th in the 16-team China League One, the division immediately beneath the CSL, following relegation as one of last season’s poorest performing sides.

Still, small mercies: the club’s supporters continue to have a team to watch. A host of Guangzhou’s former big-spending CSL contemporaries have gone to the wall.

Tianjin Quanjian, another emblem of the CSL boom-and-bust, were formed in 2006 and dissolved in 2020. The intervening years featured relocation to a 60,000-seat stadium and the employment of the captain of Italy’s 2006 World Cup winning team, Fabio Cannavaro, as manager in 2016.

Jiangsu FC folded in 2021, the year after winning the club’s only CSL championship. Hebei FC, after a £400,000 per week splurge on Argentine forward Ezequiel Lavezzi from Paris Saint-Germain in February 2016, were confirmed as goners in March this year.

That Chinese Football Association report from 2016 captured the ambitious mood: the targets were big and brash and came in a rush. A 50-point plan featured targets for infrastructure and participation, but the headline was for China to be “a first-class football superpower” that “contributes to the international football world” by 2050.

The Chinese men’s team were 81st in Fifa’s world rankings at the time of the ambitious report. Today, they stand 79th.

Even interpreting a top-10 standing as first class, at the rate of climbing two positions every seven-and-a-half years, China would attain their level in another 259 years, so the year 2282, 232 years behind schedule.

China’s women’s league had its own brief renaissance around 2016, but nothing to compare with the men’s, where transfers were predominantly funded by Chinese property businesses aligning themselves with Xi’s football ambitions.

The state-owned Greenland Holdings held a majority share in CSL club Shanghai Shenhua and funded the signing of Carlos Tevez in 2016.

The Argentine superstar was a world-renowned striker and had played for Manchester United, Manchester City and Juventus. He arrived in China to fill up his wheelbarrow to the tune of £615,000 per week, making him the planet’s highest-paid footballer.

By 2018, nine of the 16 CSL teams were owned by real estate companies. By 2020, however, the Chinese government had streamlined property businesses’ borrowing lines, resulting in critical cash shortages, unpaid debts and, eventually, financially stricken companies.

The CSL was already spooked by the money flooding out of China, and by 2020, few, if any, leading footballers had been attracted to China. For Tevez, once the money left, so did he, saying afterwards, “I was on holiday for seven months in China.”

For China 2016, read Saudi Arabia 2023. Or so goes the theory of those keen to dismiss the Middle Eastern nation’s eye-watering investment in players for its Pro League this year as unsustainable.

Detractors see a fleeting fancy of a ruler using his wealth and power for the ultimate sporting joyride at best, sportswashing its deplorable human rights record at worst, but given the vast cash outlay that has accompanied the football boom in the desert kingdom, comparisons with the CSL’s ill-fated fortunes are inevitable.

The Saudi Pro League (SPL) was established in 1976, but until the beginning of this year barely registered outside the country. Even the biggest football nut in Europe would have been hard-pressed to name more than a couple of the league’s 18 teams.

But the arrival of Cristiano Ronaldo in January changed everything. One of the most famous and high-achieving footballers of the past two decades, Ronaldo joined Al Nassr after leaving Manchester United in a blaze of fury over his reduced playing time.

Where United saw a player past his best, Al Nassr and the SPL identified a superstar, whose presence would both elevate the league’s standing, and legitimise it as an option for players choosing their next moves. They are paying Ronaldo in the region of US$200 million over a two-and-a-half year contract.

Liverpool resisted Al Ittihad’s offensive, but expect to see Saudi tanks back on the English team’s lawns inside 12 months.

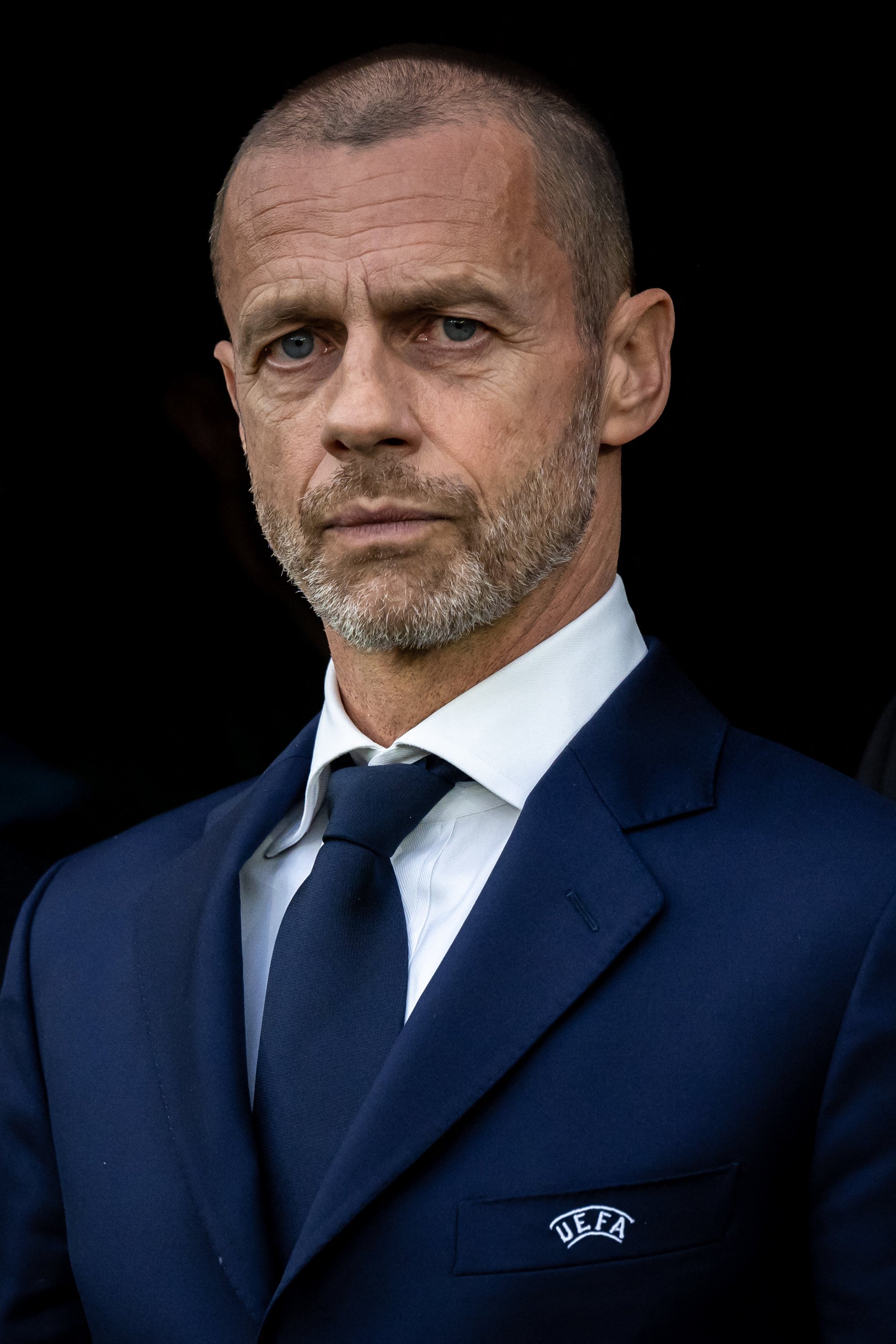

Aleksander Ceferin, the president of European football governing body Uefa, is among the vehement Saudi naysayers. He echoed many voices from the sport when he said, “Buying players towards the end of their careers for a lot of money is not a system that develops football.

“It’s not a threat. We saw a similar approach in China. Chinese football didn’t develop and [the national team] didn’t qualify for the World Cup [in 2018 or 2022].”

Saad Allazeez, the SPL’s interim CEO and vice-chairman, says the organisation’s end goal is to grow into “one of the world’s top leagues by any measure”. He acknowledged that traditionally all routes to the top of football lead to Europe, but insisted the Middle Eastern kingdom saw “massive potential to create new opportunities for players and fans in Asia and across the rest of the world.”

The question remains, can all that Saudi boom money prevent a CSL-style bust?

Saudi teams are not just pursuing over-the-hill stars.

Rúben Neves is a 26-year-old Portuguese international midfielder who commanded interest from Barcelona this summer, but he ultimately chose to sign for Al Hilal from English Premier League club Wolverhampton Wanderers. Frenchman Allan Saint-Maximin, an explosive attacker, who left another Premier League team, Newcastle United, for Al Ahli, is also 26.

Comparisons with 2016 and 2017 China disregard the difference between the power behind the CSL’s short-lived boom, and that of the splurge driven by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Academic and Middle East expert Christopher Davidson, author of the book From Sheikhs to Sultanism (2021), which details the rise of the crown prince, says that where China’s resources were finite, for Saudi Arabia “the sky’s the limit”.

“China under its form of communism was a competitive authoritarian regime, with different moving parts,” says Davidson. “There was a limit to the state resource that could be invested into that initiative.

“Saudi Arabia has a more autocratic form of authoritarianism. The young crew around MBS [Mohammed bin Salman] are committed to sports and love football. They have full control over the state’s resources for the foreseeable future, so the scale is potentially far greater than China.”

In 2017, Mauricio Pochettino, then Tottenham Hotspur manager, said the CSL had “broken” the market. Antonio Conte, in charge of Chelsea at the time, was equally affronted by an arriviste league daring to pilfer Premier League footballers and claimed the Chinese spending was “a danger for all”.

The SPL is starting its rush for global importance from a firmer footing than its 2016 Chinese equivalent. It contains clubs with some pedigree – albeit in a parochial context – and Al Hilal are the record four-time Asian Champions League winners and nine-time finalists.

The exploits of the Saudi national team at 2022’s World Cup, where they produced the shock of the tournament early on by defeating Lionel Messi’s Argentina, piqued the interest of football supporters in Europe and South America, who would have formerly dismissed Saudi Arabia as a footballing nonentity.

In 2021, the Saudi Arabian Football Federation (SAFF) implemented a seven-pillar plan, “Tactics for Tomorrow”, intended to elevate the country into “the top 20 football nations by 2034”. Pathways were created for every player aged six through to professional level.

The elite in Saudi have no real interest in what the rest of the world thinks of their human rights recordChristopher Davidson, academic and Middle East expert

The country has 5,500 registered coaches – more than 1,000 are women – up from 750 in 2018, and wants more than 8,000 by 2025. Youth football funding has increased 162 per cent since 2021. Saudi Arabia has 18 regional training centres, with six more being constructed, after none existed as recently as 2019.

“Strong foundations have been installed by the SAFF over many years and it is working really hard to produce brilliant young Saudi talent,” says Allazeez. “The league is introducing world-class international players and role models, to play with and against the best young Saudi talent.

“This is a league with a proud and long history, it is built on Saudi talent and that will always remain the case.”

The English Premier League is almost universally considered the world’s leading domestic division, generating the most money and the most viewers, and employing the best players. And there is a case for saying that today’s pushy SPL shares more with the nascent English competition than the doomed-to-fail CSL.

When England’s top league rebranded as the Premier League in the early 1990s, it was populated by clubs with more tradition and worldwide traction than their modern Saudi equivalents.

The Premier League in 2023-24 is drawing its talent from 66 countries. In its inaugural 1992-93 season, only 13 overseas players featured in the competition. The original wave of imports to the English Premier League, just like the CSL and the SPL, was also dominated by over 30s.

This year, the SPL established its Player Acquisition Centre of Excellence programme, led by former Nigeria international player and ex-Chelsea technical director Michael Emenalo, to minimise buyers risk and, says Allazeez, “bring in the right players for the right clubs on the right terms”.

With the SPL’s deep pockets, Allazeez has a unique problem, to assure that Saudi Arabia’s four Public Investment Fund (PIF) owned clubs – Al Ittihad, Al Nassr, Al Hilal and Al Ahli – don’t gain an unassailable advantage over the remaining 14 teams.

“We appreciate the league is new for fans from certain parts of the world,” he says, “but affection and interest will grow and build on the league’s massive domestic and regional fan base. It won’t take long for people to see the rivalries and the matches that divide cities and even families”.

It is impossible to analyse the Saudi push for sporting prominence without considering the accusations of sportswashing that have accompanied the staging of world-title heavyweight boxing fights, the Formula One grand prix and every other Saudi bid to host top-class competition.

The PIF – said by Bloomberg in 2022 to boast assets of US$778 billion – owns Newcastle United and funds the controversial LIV Golf, which swung a wrecking ball through the sport’s established tours.

Players defected from America’s PGA Tour and Europe’s DP World Tour, leading to major fallouts between the splitters and the remainers. Those who joined LIV were widely lambasted for chasing the oil money, without a thought for golf’s heritage.

There is a subtle but relevant difference between the SPL and the LIV, however. The golf project was set up in direct opposition to the American and European tours, so was viewed as an assault on the sport’s tradition and, most notably, a direct attack on the four major tournaments and the biennial United States vs Europe Ryder Cup event.

There are tentative plans for a Saudi bid to stage the Fifa World Cup, too, although, according to Davidson, a potential joint bid with Egypt and Greece for the 2030 competition is “going cold”, because of a reluctance to share the limelight.

“It is such an important year and opportunity for Saudi Arabia because it is so closely connected to the personal legitimacy of MBS,” says Davidson, referring to the so-called Vision 2030, under which the country aims to wean itself off its reliance on oil and attract investments in industries from healthcare to infrastructure and tourism.

“To share the stage with any other state in that year would be unacceptable. After what Qatar managed, in hosting the 2022 World Cup, pigs would fly before there would be a joint bid involving Saudi.”

Davidson says sportswashing is “next to irrelevant”, but the cries are loud that Saudi Arabia wants to scrub clean an image dirtied by human rights abuses, the oppression of women and the 2018 murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi embassy in Istanbul, Turkey.

“The elite in Saudi have no real interest in what the rest of the world thinks of their human rights record,” says Davidson. “They felt a bit of heat after Khashoggi, no doubt about that. But it is not their rationale for this.

“If the regime can promote football and other major sports, especially those that involve teams, this seems a way of transferring loyalties of citizens from tribes or clerics or religious fundamentalists, or other forces that can be reactionary or anti-regime, to relatively harmless sporting identities.”

The league has an agreement with sports agency IMG to distribute global television rights and is “actively working on securing more sponsorship deals” to supplement a “significant partnership” with video game developer EA Sports until 2026.

It is indicative of the interest surrounding the formerly anonymous SPL that broadcaster DAZN obtained rights to screen three live matches per week in Britain. SPOTV in Hong Kong will show 102 live games in 2023-24.

More than 170 countries, served by 26 broadcasters and streaming channels, will have access to live Saudi games.

Newspapers in European football strongholds are carrying match reports, along with regular updates and features from the SPL. Only 12 months ago, football folk would have looked askance at anyone suggesting the Saudi domestic game could receive this level of attention.

Publicly at least, the growing intrigue and coverage around the SPL has yet to concern officials in Europe, who remain convinced stars in their prime will prioritise winning the game’s most glamorous trophies – the league titles in England, Spain, Italy and Germany, and the Uefa Champions League, the blue-riband competition for Europe’s elite clubs – over increasing their already vast salaries.

Richard Masters, the English Premier League CEO, says his organisation was “a way off worrying” about a challenge to its global primacy.

Davidson sees the potential for the SPL to happily coexist with the major European leagues. “I wouldn’t be seeing it as a threat, if I was in charge of another league,” he says.

“I would be seeing it as an opportunity and a way to embrace another, potentially very vibrant, competitive and robust major league into the sport.”

Comparisons with the outset of China’s plan to conquer the football world remain, although Davidson believes there was a “cultural disconnect”, stemming from political mistrust between China and European counterparts that meant the CSL was always likely to struggle to make the breakthrough it desired.

“China’s history and relationship with the ancestral football nations has been much tenser than that enjoyed by Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, which have a historic affinity with football,” he says.

“Chinese state capitalism is very different from Gulf capitalism, which is still embryonic, but the direction it’s going seems to be trying to emulate lots of aspects of Western capitalism, especially in relation to branding.

“That lends itself very well to shirt sponsorship, stadium advertising and so on. That potential didn’t seem as clear in China.”