- Using a Western interpretation of a 2,400-year-old document, Beijing seeks Unesco’s stamp for a line of monuments, many badly restored or entirely rebuilt

“No other city in the world,” wrote architect Liang Sicheng for the People’s Daily in 1951, “has so imposing a pattern, with so neat an arrangement of the built spaces. Neither is there another city so splendid with those golden glazed tiles, those beautifully painted timber structures and those palaces and temples organised into a harmonious whole.”

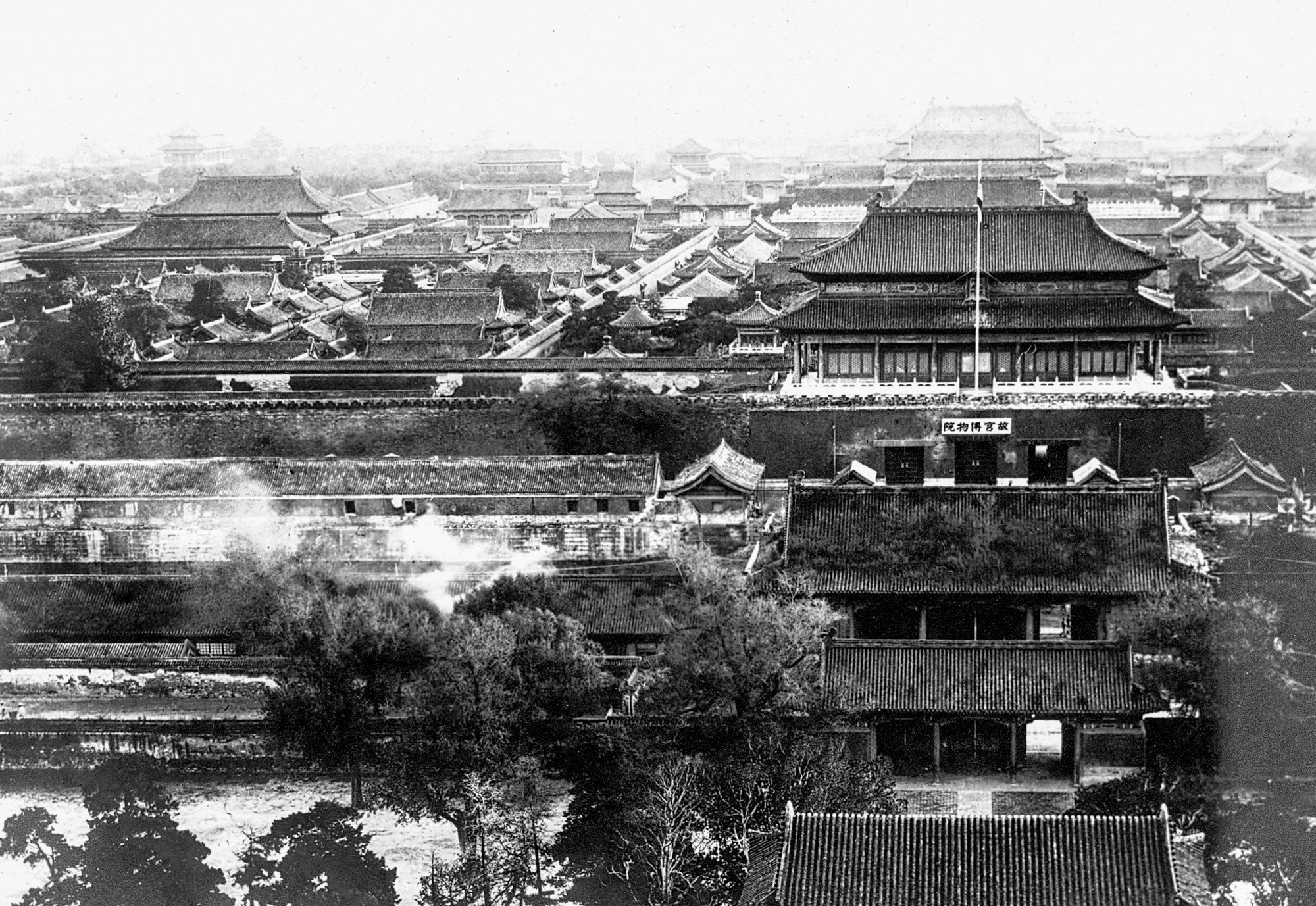

Sitting atop Beijing’s Jingshan (Prospect Hill) and looking south over the yellow roofs of the former Imperial Palace, the doyen of Chinese architectural historians could view in the distance a series of imposing city gates (men) rising from the sea of grey roofs beyond, with major palace buildings and gate towers standing in a straight line that divided the ancient Chinese capital symmetrically in two.

Liang rhapsodised about this zhongzhouxian, or Central Axis, stretching from the Yongdingmen, the central gate in the south wall of the rectangular Outer City, through the Zhengyangmen in the south wall of the square Inner City, then on north through the centre of the palace and on to the Drum and Bell towers.

More than 70 years later, the People’s Daily and many other official Chinese media outlets have again had much to say about Beijing’s layout, repeatedly announcing that the Central Axis and the historic buildings along it will be inscribed on the Unesco World Heritage List, although they failed to agree on what, or when.

But earlier this year, a February 28 article in China Daily confirmed that an application to list the Central Axis had finally been submitted.

The proposal reportedly included a 7.8km-long (4.9-mile) axis with a 5.9 sq km heritage area around it, all standing within a buffer zone totalling 45.4 sq km of the heart of Beijing, and including 15 historic sites.

Beijing’s plan is supposedly from a 2,400-year-old Chinese document called the Kao Gong Ji (Artificers’ Record), demonstrating the longevity and authenticity of the idea of the Central Axis. Historic buildings dating back as far as the 1420s still stand on or near it, and two sets of them, the Imperial Palace and the Temple of Heaven, already have World Heritage listings.

So the application’s success seems assured, especially since China Daily suggests that the “Unesco official website” acknowledges its credibility, saying, “The Central Axis is the physical carrier of the ancient Chinese ritual system […] and [a] typical example of traditional Chinese social governance applied to urban planning.”

But here the problems begin.

Warsaw was nominated and accepted as a World Heritage site when 85 per cent of it had been destroyed during the second world war.Dr Dacia Viejo Rose, associate professor of cultural heritage and the politics of the past at Cambridge University

The Kao Gong Ji makes no mention of a zhongzhouxian or indeed of a line or axis of any sort.

Many of Liang’s “golden-glazed tiles” have been inauthentically replaced, many of his “beautifully painted timber structures” have since been destroyed, and many others have been repainted with acrylics or entirely recreated in concrete.

Much of his “harmonious whole” has now wholly disappeared, some replaced with Disneyfications of historic housing and shops, and with a vast windswept square lined with 75-year-old buildings in the sort of neoclassicism beloved of Hitler and Stalin.

And all of this took place on the watch of the same Beijing cultural heritage authorities now supposedly championing the importance of conservation.

The sentence taken from the “Unesco official website” is not the imprimatur implied, but is from a document written by the Chinese heritage authorities, and the World Heritage Committee states on the same page that it takes no position on the contents.

And when it comes to the meanings of heritage, conservation, authenticity and integrity in China, there are a number of questions the experts examining the latest Beijing application should be asking themselves.

To be considered for World Heritage listing, a site must be shown to meet one or more of 10 criteria, and take into account protection, management, authenticity and integrity.

A State Party (signatory) to the Convention must first add a proposed site to a Tentative List.

The Central Axis Tentative List document, submitted in 2013, cites the Beijing Zhongzhouxian as evidence of human creative genius, as exceptional testimony to a civilisation, as an outstanding example of an architectural ensemble, and as having an association with living traditions. It also devotes several paragraphs to claims for the Central Axis’ authenticity and integrity.

It cites the 3rd century BC Kao Gong Ji, which describes the work of artisans such as wheelwrights, tanners and bell-makers, and in a section on construction workers devotes part of one paragraph to a brief description of the layout of the “king’s city”.

That is to be square, and to have three gates on each side, with three main streets running north-south and three east-west between opposite gates. It specifies the locations of palace, market and two temples.

But there is no mention of an axis or line, and Beijing’s layout, whether Mongol Yuan of 1267 or Chinese Ming of 1420, on roughly the same plan, only approximately conforms to the Kao Gong Ji ideal.

The palace and the temples it mentions are in the locations prescribed. But the northern wall of the Inner City lacks a central gate, so the axis has to end at the Drum and Bell towers, well short of the north wall.

The walls of the Inner City are not the prescribed length, and the wider rectangle of the Outer City, whose walls were built in 1553, is entirely outside the Kao Gong Ji square plan, and therefore so are its Yongdingmen central south gate and the southern 3km of the Central Axis.

But then that length does tend to alter according to political convenience.

But to include even the Olympic venues in a heritage application would be to make the definition of “heritage” as elastic as the line itself, while stretching it beyond credibility until perhaps it snapped. So it has conveniently contracted again.

It seems that the modern idea of the axis more arises from Liang’s praise of it, appealing to national pride, and so being quoted and repeated ever afterwards.

Axis and symmetry mean the same thing. Kao Gong Ji doesn’t use [Central Axis], but it does describe a symmetrical pattern, and this symmetry is actualZhu Jianfei, professor of East Asian architecture at Britain’s Newcastle University, referring to the 2,400-year-old Artificer’s Record

The University of Pennsylvania-educated architect was the first to use the expression zhongzhouxian, and this is important in the development of the idea, says Yu Shuishan, an associate professor at Northeastern University, in the United States.

“We know in European Beaux Arts architectural education that zhouxian – axes – are very important,” he says. “You have all that axiality and symmetry in classical revival architecture. Liang got all those ideas about axes, and about classical orders. It’s all from Greco-Roman architecture.”

Not for the first time, it seems Western ideas are being imported and then exported again to an admiring foreign audience. And according to a People’s Daily article of July 2018, “international experts” will “help explain the importance of the Central Axis”.

Any walled city not built to take advantage of topographical features such as rivers or high ground will tend to be square. But all squares have axes, and it needs no 3rd century BC text to create them.

The equal spacing of entrances and balanced distribution of facilities inside is only common sense, and was a feature of most other walled cities in China, including almost all capitals.

China’s ancient Shang dynasty gives up more secrets from 3,600 years ago

Zhu Jianfei, professor of East Asian architecture at Britain’s Newcastle University, sees no importance in the fact that ancient texts make no mention of axes.

“Kao Gong Ji is a very old classical text, about the layout of an ideal capital city. But Liang Sicheng is a modern Chinese, educated in America, so when he comes to describe China he uses a lot of modern terminology,” he says.

“And a lot of those terms, although they are written in Chinese, are imported words like architecture, revolution, communism, democracy and also zhongzhouxian – central axis.”

Regardless, he says, the symmetry of Beijing is there.

“For an architecture student or scholar, any symmetry means an axis, like a face. Axis and symmetry mean the same thing. Kao Gong Ji doesn’t use the word zhongzhouxian, but it does describe a symmetrical pattern, and this symmetry is actual.”

As for when Beijing’s design does not correspond to the Kao Gong Ji ideal, Zhu argues in a 2018 paper that the book should be viewed as providing “an abstract and relational pattern of distribution and configuration”.

The general layout, to which Beijing mostly conforms, is of primary importance, while the ways in which it does not are only secondary.

But this seems a self-fulfilling argument. The city’s design will always be found to have its origins in the Kao Gong Ji one way or another.

Pro-Beijing think tank to turn historic Hong Kong mansion into health centre

Zhu concedes that other influences are also at play. The lack of a central northern gate perhaps reflects a feng shui-related recommendation not to sit with your back to a door, as the emperor would to the gate when sitting on his throne.

Evil influences were always seen as coming from the north, be they cold winds or nomadic tribesmen such as the Mongols and Manchus.

The Kao Gong Ji does offer clear instructions on using the Pole Star to align cities to the cardinal points.

Modern maps of Beijing show the axis misaligned to true north as a result, reflecting the Pole Star’s position at the time. The Imperial Palace is sometimes referred to as Zijincheng, or the Purple Forbidden City, but Zi in this case refers to the star, not the colour.

But in the end it’s finding the historic buildings in a line that is used to make the case. Liang saw the walled Forbidden City, nestled inside the larger walled Imperial City, sitting within the still larger Inner City, with the Outer City rectangle added on the south side, together roughly in the shape of the character 凸.

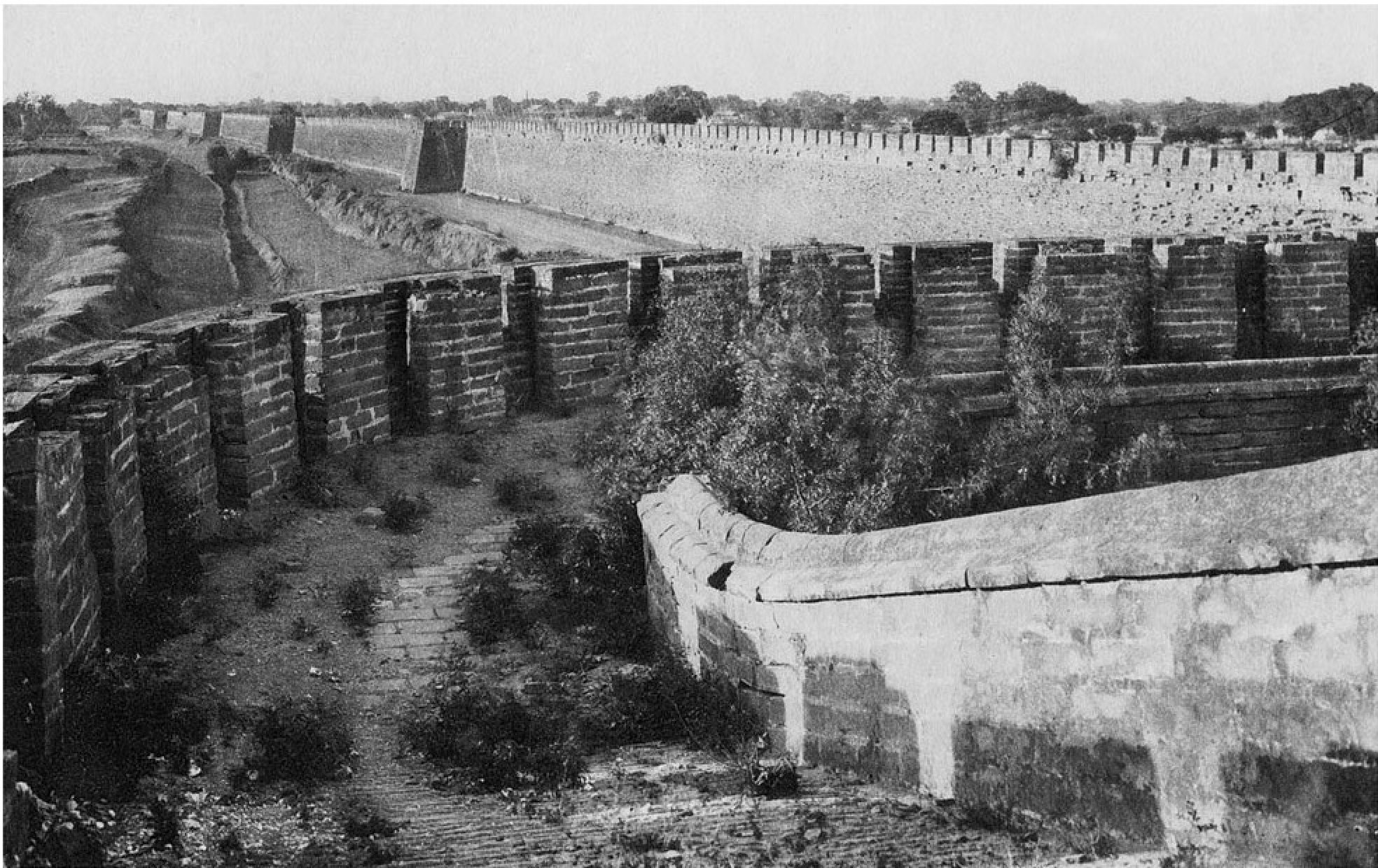

But the walls and the gate towers he saw, and that provided the symmetry that defined the line, were almost all pulled down within a decade or so.

The tentative document mentions the Tiananmen Square “complex” as one of the sites to be included in the application. But the square was formed in the late 1950s and expanded to roughly its present size only in the late 1970s, by pulling down lengths of wall, acres of historic ministries and storehouses, and several gate buildings, including the 450-year-old Zhonghuamen in the centre, all part of Liang’s “harmonious whole”.

The buildings that form the sides of this “complex” to east and west include the National Museum and the Great Hall of the People, built in the late ’50s.

The square contains the Monument to the People’s Heroes, completed in 1958, and the Mao Zedong Memorial Hall, which holds the embalmed corpse of the Chinese leader, only completed in 1977 on the site of the destroyed Zhonghuamen.

Both stand on the axis, but neither has any relevance to Yuan or Ming city planning, and neither, despite their connection to tumultuous events affecting hundreds of millions of people, is historic in the same sense as the surviving palaces and towers.

The Mao Memorial is an important building … The same is true for Tiananmen Square, the Great Hall and the museums. But they are the record of a totally different historical periodYu Shuishan, an associate professor at Northeastern University, in the United States

Zhu describes the Central Axis as “the strongest organising element of the whole plan”, and says that after the completion of the Outer City wall in 1553, “Beijing reached its final form”.

But if the 1553 extension is to be accepted then why not accept subsequent changes, so long as they keep in mind the city’s now heavily compromised symmetry?

Perhaps the “final form” can be defined as 1977, making it reasonable to include the modern monuments, but unreasonable to appeal to plans from more than 2,000 years ago.

Liang Sicheng (1901-1972) began a struggle to preserve the ancient city even before the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China. And in a 1950 paper, co-authored with University of Liverpool-educated architect Chen Zhanxiang, he proposed the full adoption of modern materials and international design styles to build a new administrative centre to the west on a site already cleared for this purpose by the Japanese during their occupation.

He also wanted to preserve all of old Beijing within the city walls, and build all new towers outside the walls. Beijing residents remain in almost unanimous agreement to this day.

The old city lacked adequate accommodation, transport, sewerage or water supplies to accommodate a vast new bureaucracy, he pointed out.

But Liang found himself at odds with other Party officials, with other architects, with influential Soviet advisers who insisted on Stalin’s policy that new construction should have a local flavour, and with Peng Zhen, Beijing mayor at the time.

He was accused of daring to criticise even Mao himself, saying that the Chairman knew nothing about architecture.

Liang’s proposals were rejected, and eventually he and other similarly minded architects were driven off the planning committee, leaving all decisions to be made on the basis of politics.

The destruction of the city walls was made a question of class struggle, and they were pulled down in the ’50s, along with most gate towers.

Many temples and pailou (memorial gateways) were also pulled down to facilitate the creation of broad boulevards. Liang’s suggestion that memorials should be dismantled with care and rebuilt elsewhere was ignored.

Just as he had forecast, traffic became a problem, and in some cases the water pressure was inadequate to reach beyond the second floor of new towers.

But if Liang’s lyrical descriptions are the true origin of the idea of the city’s axis today, then perhaps it should also be taken into account that most of what he described has disappeared, even on the axis itself.

The China Daily report lists “15 key sites, the majority of them built in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644)”. But the truth is more complicated.

The Yongdingmen is a modern rebuild of 2003 (and in roughly Qing style, not Ming) lacking its accompanying arrow tower and enceinte, or the city wall that gave them meaning.

The “Road remains in the southern section”, supposedly stretching north from there, are a creation of the same date.

The already listed Temple of Heaven complex’s highly photogenic centrepiece, the circular Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, was most recently rebuilt in 1889 using timber imported from Oregon, in the US.

The corresponding Altar of Agriculture compound has been built over save for all but a tiny fragment, its impressive Hall of Jupiter, found to be near collapse in 1998, restored with foreign money.

The twin towers of the Zhengyangmen were originally constructed in 1420 and 1439, but the outer Arrow Tower of brick and stone was lost to a fire started by the Boxer rebels in 1900.

Fifteen years later German architect Curt Rothkegel, with a liking for art nouveau, rebuilt it adding distinctive white eyebrow-like decorative details above the windows.

Further north, other gates are visible in footage of Mao arriving to climb to the Tiananmen rostrum and announce the creation of the People’s Republic on October 1, 1949. But when he mounted again to celebrate the PRC’s 10th anniversary, much of what he could have seen previously had been destroyed.

Even the hugely symbolic Tiananmen was entirely shrouded in scaffolding and matting, and secretly pulled down in 1969, then rebuilt largely in reinforced concrete, and with a lift inside.

Five small arched bridges leading to the gate are to be listed, as are the Altar of Land and Grain, in Zhongshan Park to the west, and the Imperial Ancestral Temple to the east, its main hall truly the last significant substantially Ming structure surviving in Beijing.

Beyond the Tiananmen stands the nearly identical Duanmen, also to be listed, and the Imperial Palace. According to Aurelia Campbell, professor of Asian art history at Boston College and author of What the Emperor Built (2020), this is more a copy of an earlier Nanjing palace than anything else, and almost all of it is now Qing dynasty.

This desire to imitate also drove the construction of Jingshan, Liang’s viewpoint, using the rubble of the Yuan city that the Ming pulled down.

A further northern entrance to the Imperial City also came down in the 1950s, but the Wanning Bridge beyond where it stood is said to be Yuan. Its original stonework is heavily compromised, buried under a busy road, and its balustrades were substantially replaced in 2000.

The Ming version of the Drum Tower was constructed in part with material from the Yuan one, but has been rebuilt at least five times since. The Bell Tower, just north, and the supposed end of the axis, was reconstructed in stone in 1745, during the Qing dynasty, not the Ming.

Unesco can’t protect World Heritage sites – just look at China

Whether the appeal is to the Kao Gong Ji or to Liang, is there really much left? According to new ideas of what constitutes heritage, perhaps none of the rebuilding really matters.

To the man on the history tour omnibus, the meanings of words such as heritage, conservation, authenticity and integrity seem quite straightforward.

The antiquity and rarity of a site, which is physical evidence of a certain culture at a certain time, means it should be preserved. And its authenticity and integrity are maintained by performing only such maintenance and repairs as may be unavoidable, using materials and methods that match those used originally as closely as possible.

But for decades now there has been a fierce debate on these matters between academics, practitioners of heritage conservation and those whose heritage is in question, about what these terms should mean, and who has the final say on what is of value.

“The slipperiness with authenticity probably starts in 1994,” says Dr Dacia Viejo Rose, associate professor of cultural heritage and the politics of the past at Cambridge University and director of the Cambridge Heritage Research Centre.

That year, she explains, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), an independent professional body advising Unesco, produced the Nara Document on Authenticity. This replaced earlier thinking on material authenticity with references to intangible values, meanings and practices.

The everyday idea of conservation was perhaps Eurocentric, in the context of brick and stone, and the spur for fresh thinking was partly the Japanese tradition of pulling down major wooden shrines and rebuilding them on a regular cycle. They planned for decay from the start.

“The authenticity lies in rebuilding them, not in maintaining the old structures,” she explains. “The European idea that was predominant in Unesco of physical integrity was being questioned from different groups of countries whose ideas of authenticity and heritage lie elsewhere than only in the material.”

So perhaps everything Chinese can be rebuilt, too. But while Japan makes exact copies of what it is replacing, China’s simulacra often resemble the originals only roughly in form, and not at all in materials. And there’s no plan.

Ancient Chinese city named as latest World Heritage site

The ICOMOS Burra Charter of 2013 acknowledged the relationship of indigenous Australians to the landscapes they inhabit, and added the idea that places of cultural significance are of “aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations”.

Heritage is in the eye of the beholder, and conservation becomes about looking after a place so its cultural significance is retained. It’s an associative value, not something inherent in objects or places, and it can change over time as attitudes change.

“Time is still part of it,” explains Viejo Rose, “not in the fixed way of that was then and this is now, but in this kind of continual legacy in which we’re constantly reconfiguring the past based on the needs of the present and the aspirations for the future.”

This seems a fair description of the Beijing Central Axis application.

“But if heritage is a process of meaning-making by which we reconfigure the past to meet the needs of the present and for the future that we want,” says Viejo Rose, “then of course it’s political.”

In China, the main reason for seeking World Heritage listing is to increase tourism revenue, and for a country given for centuries to making lists of beauty spots, the Unesco World Heritage List is the ultimate approbation. Tourism numbers and gate receipts all swell, often by many multiples. But in Beijing excess visitor volumes are already a problem.

The Central Axis proposal gets round the one site per country per annum limit in operation since 2018, adding 13 locations for the price of one. These are less well known, but will be able to claim World Heritage glamour to draw in the crowds.

States Parties work with the World Heritage Centre to develop their home-produced tentative documents into Nomination Files. Each nomination is then evaluated by independent advisers including ICOMOS, which make recommendations to the World Heritage Committee.

East Asian sites of natural value given Unesco World Heritage status

The contents of the Nomination File will not be revealed until just before the meeting that considers the application, in mid-2024. But after listing it is likely to be claimed that the world has endorsed modern pro-communist monuments and by association Chinese communism itself.

The argument will have become perfectly circular: the orientation of selected historic structures demonstrates the significance of the axis, and the presence on the axis of modern political structures demonstrates their historical importance.

“The Mao Memorial is an important building, but not in the way the Chinese government would say,” says Yu. “The same is true for the vast Tiananmen Square, the Great Hall and the museums.

“They are all very important buildings, as well as the Monument to the People’s Heroes. But they are the record of a totally different historical period and in a totally different way, compared to how they might frame it and put it in a report.”

And it is common to many political announcements that they are designed to make us admire a new policy while distracting from questions about what caused that policy to become necessary in the first place.

Since 2005, the Chinese press has announced every year or two that satellite cities would be created around Beijing to allow people to live closer to their places of work and to cut down congestion in central Beijing – the solution Liang proposed in 1950.

In July 2014, the municipal government banned construction of new hotels, exhibition halls, universities, hospitals, office buildings, manufacturing and wholesale businesses in the Inner City, for reasons of “scientific development” – again, Liang’s recommendation.

Now, “Look at what we’re doing,” says this application, “and don’t remember that we were told to do it 70 years ago, and before we tore down almost all of what we’re now asking credit for conserving.”

China’s Maritime Silk Road port Quanzhou wins World Heritage listing

When the addition of Warsaw to the World Heritage List was proposed, the Poles had rebuilt a city that by 1944 had been 85 per cent razed by the German air force and artillery. Historical documents, postcards and even 18th century paintings were used to recreate what had been destroyed.

But in Beijing, the rebuilding has been incomplete, mostly without authenticity or integrity, and the only enemy of Chinese historic buildings has been the Chinese themselves.

China now has 42 properties on the cultural heritage list and seems intent on overtaking Spain (43), Germany (48) and Italy (53). But to have a site recognised as of significance to the whole of mankind under the terms of the World Heritage Convention is equally to relinquish sole responsibility for its preservation and maintenance, and to cede the right to act without the approval of the World Heritage Committee.

Yet time after time, at multiple sites, China has faced criticism for acting without a plan of any kind, let alone one that had been approved, for undertaking renovations without consultation, for employing inauthentic materials and techniques, and for breaching agreed limits on visitor numbers.

World Heritage Committee meetings in 1994, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2009 discussed problems at the Imperial Palace (inscribed 1987). These included threats from air pollution, erosion, commercial development, housing, weaknesses in management, lack of planning, the impact of tourism, displacement of local populations and the effects of traffic.

Some critical ICOMOS inspection reports have disappeared from Unesco’s site, whose specific criticisms included the use of non-traditional paints, the inauthentic and monotonous reglazing of roof tiles, conspicuous overall changes to the appearance of many buildings, lack of documentary support for continuing repairs, excessive haste and a plan to construct a “one-storey building within a courtyard of the Imperial Palace” in breach of World Heritage operational guidelines.

A monitoring mission in 2005 stated that “no new buildings should be planned within the compounds of the Imperial Palace”, yet one complex directly within its precincts, the Jianfu Gong, which burned down in 1923, has been reconstructed from the ground up and was completed in 2009. Its interior is modern, designed by US architects.

This was hardly a well-kept secret, as there was widespread reporting in 2011 of the site’s existence and public outrage at its use as a private club. The Jianfu Gong appears on the Palace Museum’s website, but an otherwise detailed report of its history somehow neglects to state that it has suddenly reappeared from nothing.

Yet there is no mention in committee meeting minutes of this fresh construction, or any sign that any World Heritage body or agency was consulted or involved.

Indeed, there has been no mention of the Imperial Palace since 2009, while further new construction is currently under way in the palace’s southwest corner.

Hong Kong’s Blue House wins Unesco’s highest conservation award

In 2003, China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage informed the World Heritage Centre that redevelopment of ancient housing in the Nanchizi area, within the palace’s buffer zone, “was beyond the scope of protection under the World Heritage Convention”, and China Daily reported in September 2004 that a buffer zone “was not required by the World Heritage Committee”, despite the committee clearly being of a different opinion.

Nine hundred traditional siheyuan courtyard houses were destroyed in what was also supposedly an area that the city had marked out for heritage protection in its own terms. But “protection” meant use of the bulldozer.

Brand new Ming dynasty courtyard houses sprang up but now with two storeys, with old pillar bases built sideways into the walls as decorations, and with anachronistic up-and-over garage doors, all about as authentic as a Chippendale television cabinet.

A few residents were allowed to return to subsidised housing, but other properties appeared on the market for 8 million yuan, suggesting huge profits for developers and their government partners.

While the original residents had been mostly driven away, security personnel patrolling the alleys revealed that many senior officials from that district’s local government now lived there.

The China Daily story went on to admit that the surroundings of the palace had suffered from improper planning and redevelopment, that traditional housing had been destroyed with minimal compensation, that new high-rises were encroaching, and cynically to insist that, “a protective buffer is urgently needed to strengthen protection of the culture relics around the palace, yet with the harmony between the palace and its surroundings unspoiled”.

In 2009, Dresden, in Germany, was removed from the World Heritage List for adding a much-needed bridge across the Elbe, and in 2021 Britain’s Liverpool was removed for the redevelopment of disused dockland area “detrimental to the site’s authenticity and integrity”. But the Imperial Palace survives.

“There are all kinds of underhanded ways that countries learn that if they want to make any changes and repairs [to a site] they’d better do them before they nominate it for World Heritage,” says Viejo Rose, “because once they do nominate they’re very restricted in what they can do.”

Despite repeated requests, Unesco failed to supply an interviewee or answers to written questions on these matters, or copies of critical reports now missing from its site.

Six Unesco World Heritage sites in danger of being delisted

In 2018, the People’s Daily reported that there was still much renovation to be done to the backstreets and alleyways in the proposed Central Axis buffer area. “When necessary, residents in heritage areas will be relocated to return the heritage sites to the original state,” it said.

“Using nominations of World Heritage sites to expel undesired populations from a site has been used by loads of countries,” Viejo Rose says.

She declines to name names, but it is easy to find studies suggesting such moves at Jordan’s Petra and Mali’s Djenné, for instance. In Beijing’s case, the profits from using heritage listing to evict inconvenient residents in order to “renovate” prime city central residential areas must be very tempting indeed.

The 10-year gap between filing a Tentative List document and moving to nomination begins to look very convenient.

But the idea of heritage remains important, says Viejo Rose, “because it is something that is instrumentalised and used constantly to justify actions and to redefine notions of identity. It’s an incredibly central element to the ways in which societies and individuals make sense of themselves.

“It’s not just China doing it. Every country in the world is doing it.”

But when it comes to adding the Central Axis to the World Heritage List, some may say it is time to draw the line.