- Lianzhou Foto was halted by the pandemic but cracks had begun to show years earlier as authorities increasingly removed exhibits, reining in self-expression

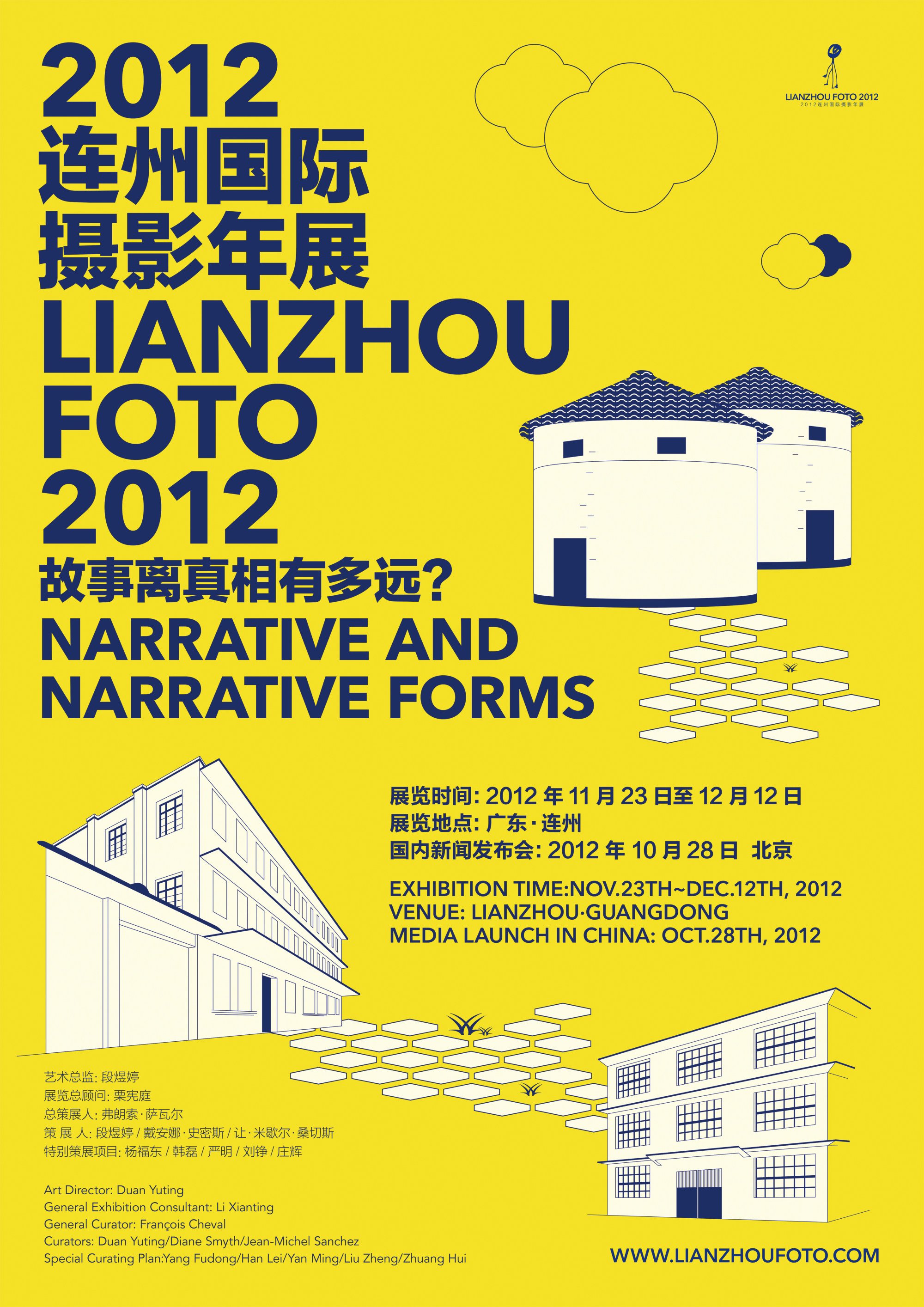

Following a chance encounter between a small-town mayor named Lin Wenzhao and an equally ambitious photo editor called Duan Yuting in 2004, the idea for a contemporary photography festival in an obscure mountain town between the southern Chinese provinces of Guangdong and Hunan was born.

It was not long before the Lianzhou International Photo Festival entered the photography world’s lexicon, often uttered in the same breath as Les Rencontres D’Arles, a similarly experimental photography festival held annually in southern France.

Later rebranded Lianzhou Foto, from 2005 until 2019, the event grew year on year in prestige, scope and quality.

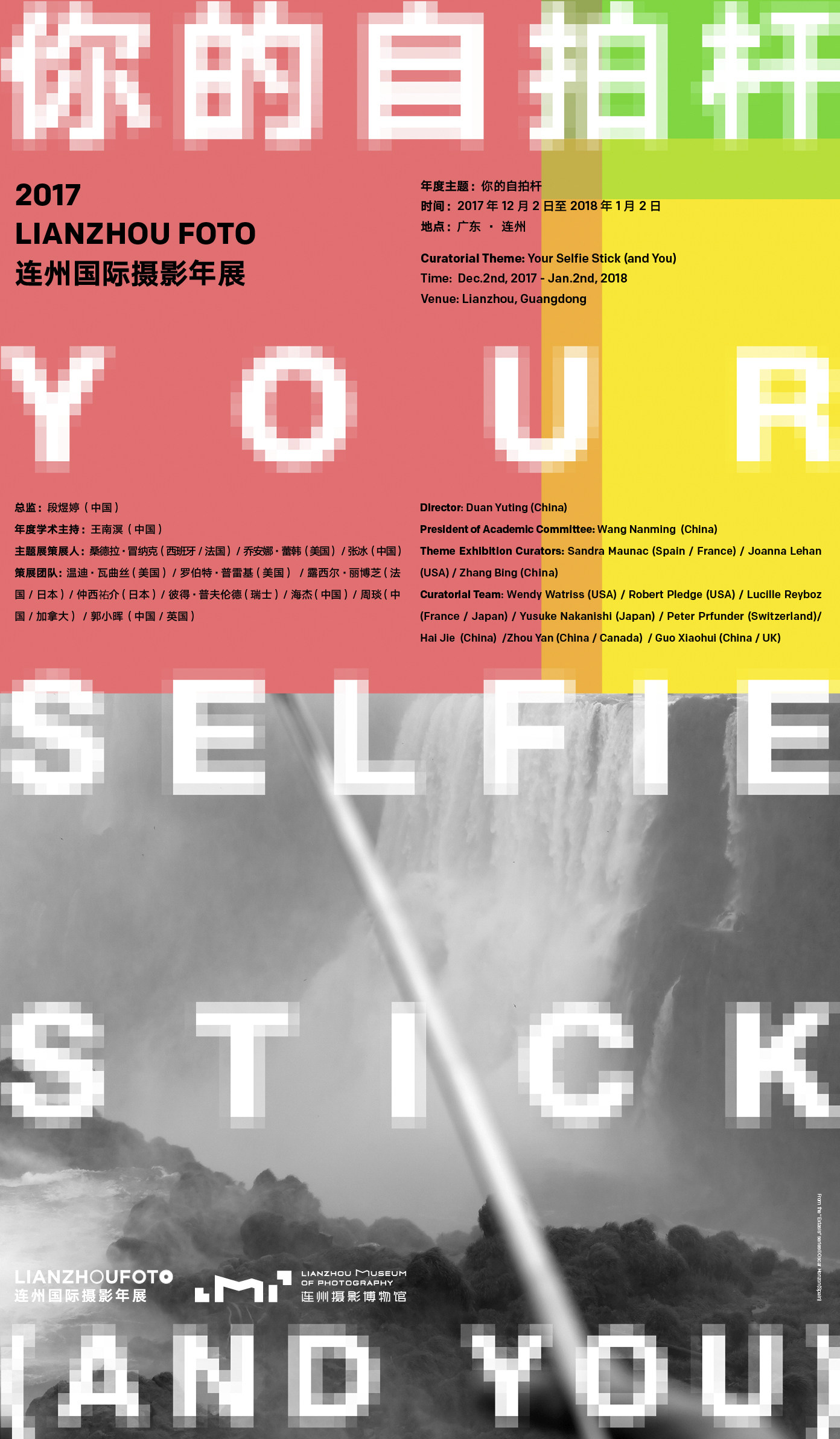

In 2017, the Lianzhou Museum of Photography was inaugurated, supplanting the Candy Factory, a disused sugar mill the festival organisers had previously used to exhibit artwork. The landmark building cemented Lianzhou’s status as a “City of Photography in China”, as the government, keen to promote Lianzhou as a tourist destination, branded it.

But ideological cracks were beginning to show, and just before the 2017 “Your Selfie Stick (and You)” edition kicked off, several exhibitions were cancelled at the last minute by state censors.

In north China, the Beijing Literature Festival, which had attracted scrutiny in 2016, cancelled its 2017 edition, while the Strawberry Music Festival was axed just two weeks before it was supposed to have been held in Grand Epoch City, in Hebei province.

The arts, it was sensed, were coming under increasing surveillance, and the space for free expression that had emerged during China’s reform era was contracting. But the Lianzhou Foto team, working from their office in Guangzhou, laboured on, hopeful that Duan’s owlish stewardship would help protect the festival as much as its location, “where the mountains are high and the emperor is far away”.

Neither did. Almost a third of the photographic works in 2018’s “The Wind of Time” – 120 images in total – were removed by officials before the festival began. The situation worsened at 2019’s prophetically titled “A Chance for the Unpredictable”, with pictures being removed right up until the opening ceremony.

Effusive official speeches made no mention of the blank spaces on gallery walls just before the fireworks lit up the sky above the Cultural Plaza. Exhibiting artists, curators, critics and attendees, gathering in Lianzhou’s riverfront restaurants, began to debate the future of a festival that had become, for them, an annual pilgrimage, as significant as Glastonbury is to British festival-goers.

But such speculation would be overtaken by greater concerns, as Covid-19 emerged during the 15th edition of Lianzhou Foto, bringing down the curtain on all such public gatherings of scale, ranging from the Canton Fair in Guangzhou to the OCT-Loft Jazz Festival in Shenzhen.

Three years on, Lianzhou Foto remains on hiatus.

Duan describes Lianzhou in the mid-to-late 2000s as a city of “narrow streets just wide enough for bicycles” with “a few grubby restaurants” connected to the world by “a snaking mountain road”. So, it is easy to imagine how an impressionable schoolgirl might have followed photographers around in the same way as young fans pursue Cantopop stars in Hong Kong.

But even as the streets were widened and signs of modernity such as mobile-phone shops and fast-food outlets began to emerge, Tang Ying, born in 1999, remained a steadfast supporter of her hometown’s annual photographic gathering.

Tang shows off her collection of Lianzhou Foto memorabilia: brochures, entrance tickets, autographs and photos she took of the artists over 14 years of exploring the galleries.

“My father held my hand and took me to the second edition, in 2006. It was amazing,” she says. “Lianzhou Foto was much livelier than Lunar New Year festivities. As I grew older, I started to go by myself. It was just such a relief from my boring school days.

“When I was in primary school I took a small notebook in which I wrote down a few sentences in English. I tried to use them to talk to foreigners who took part in the photography festival. I collected their autographs and took their pictures, which I then printed out.

“When I was in middle school, I had a lot of homework but I told my parents I had finished it to make time to visit all the exhibitions. When I was in high school, I even skipped self-study just to meet friends I’d met at the photography festival.

“I eventually went to university in Guangzhou, but I brought my roommates back to Lianzhou to participate in the photography festival each year. I was so proud of it.”

At the end of the millennium, Duan moved from Taiyuan, in north China, to Guangzhou, to work in the southern city’s flourishing news media. But when she encountered then Lianzhou mayor Lin Wenzhao in the city of Qingyuan while teaching a photography workshop in 2004, her destiny – and that of Chinese contemporary photography – was forever changed.

“Contemporary photography emerged relatively late in China, some years after the Cultural Revolution,” says Duan. “In the 1980s and through the 90s, a growing sense of individualism saw people beginning to explore literature, film and, of course, photography. But when I went to work at People’s Photography [a Chinese photography magazine] as a photo editor in 1996, I found that photography was used for the purposes of the media and most practitioners were journalists.

“I became aware that much of it was stale, it was inexpressive and uncritical – everyone went off to Tibet to photograph the mountains or found some remote villagers to shoot. People weren’t yet using their cameras for anything more than capturing light.”

Duan wanted to showcase “artists who expressed themselves through the medium of photography”. It would be a marriage of convenience but it would work. Notwithstanding her left-field vision for the festival, Duan recalls that the local cadres she was tasked with working with were accommodating and diligent.

“I didn’t notice it at the time but looking back it was really a different era,” she says. “All regional governments across China were trying to develop culture. It was considered important to fulfil people’s cultural needs. The idiom ‘culture paves the way, economics comes to sing the opera’ was being banded around everywhere.

“Lianzhou was small, just a county-level city, which is just one level above a village in administrative terms. It looked like it was forever trapped in the 1980s. But the local government was very supportive. They’d just built a library and culture centre and needed content. We were able to step in and fill that space.”

It was also important for Duan and company to organise something truly wide-ranging, in an age when China was opening up to the world ahead of the 2008 Olympics and the word guoji – international – was essential to any kind of branding.

“I reached out to [French curator] Alain Jullien, who I’d worked with when I’d been an assistant at the Pingyao International Photography Festival, when I lived in Shanxi, and he brought several European artists along to the first Lianzhou festival, in 2005,” says Duan.

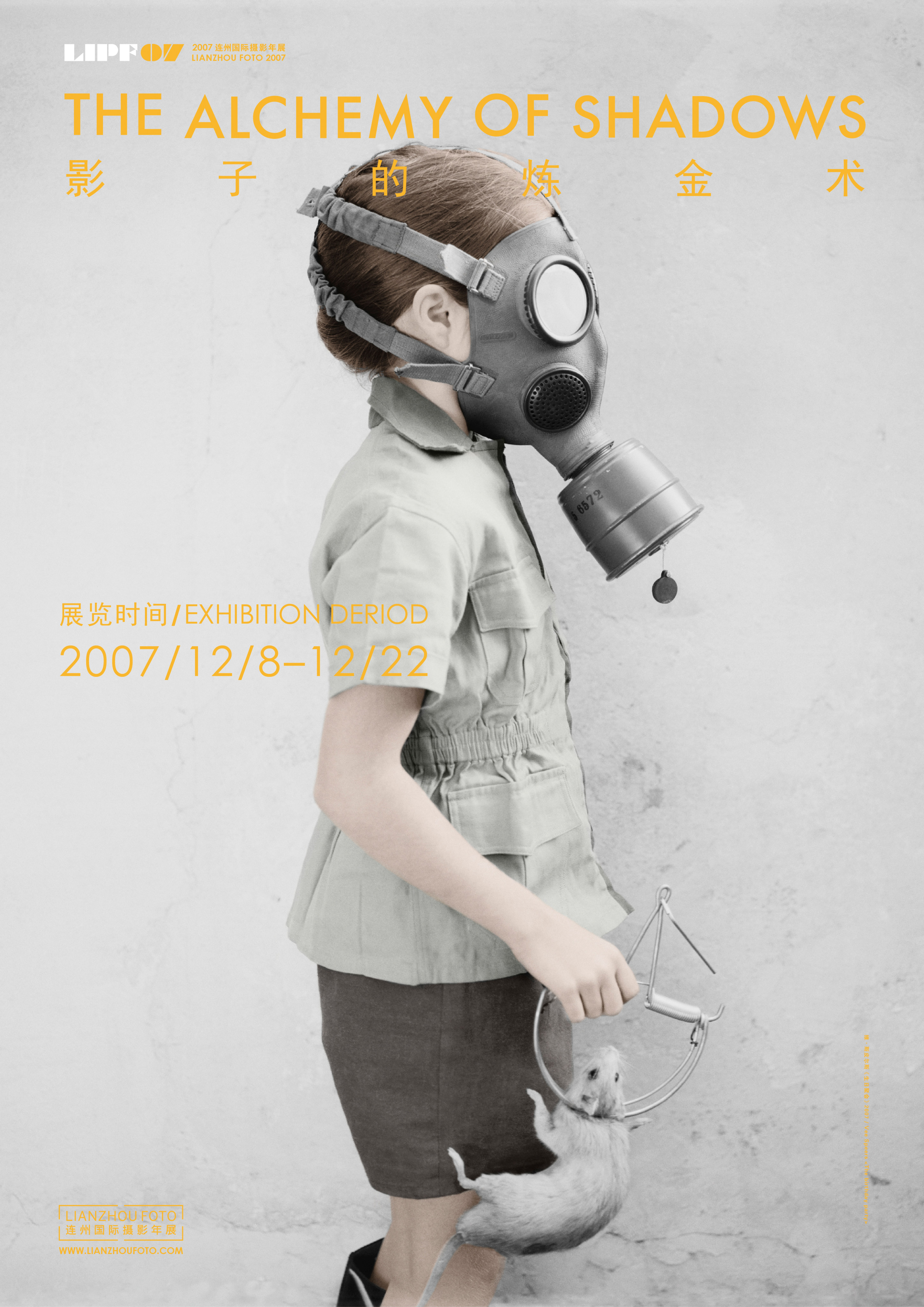

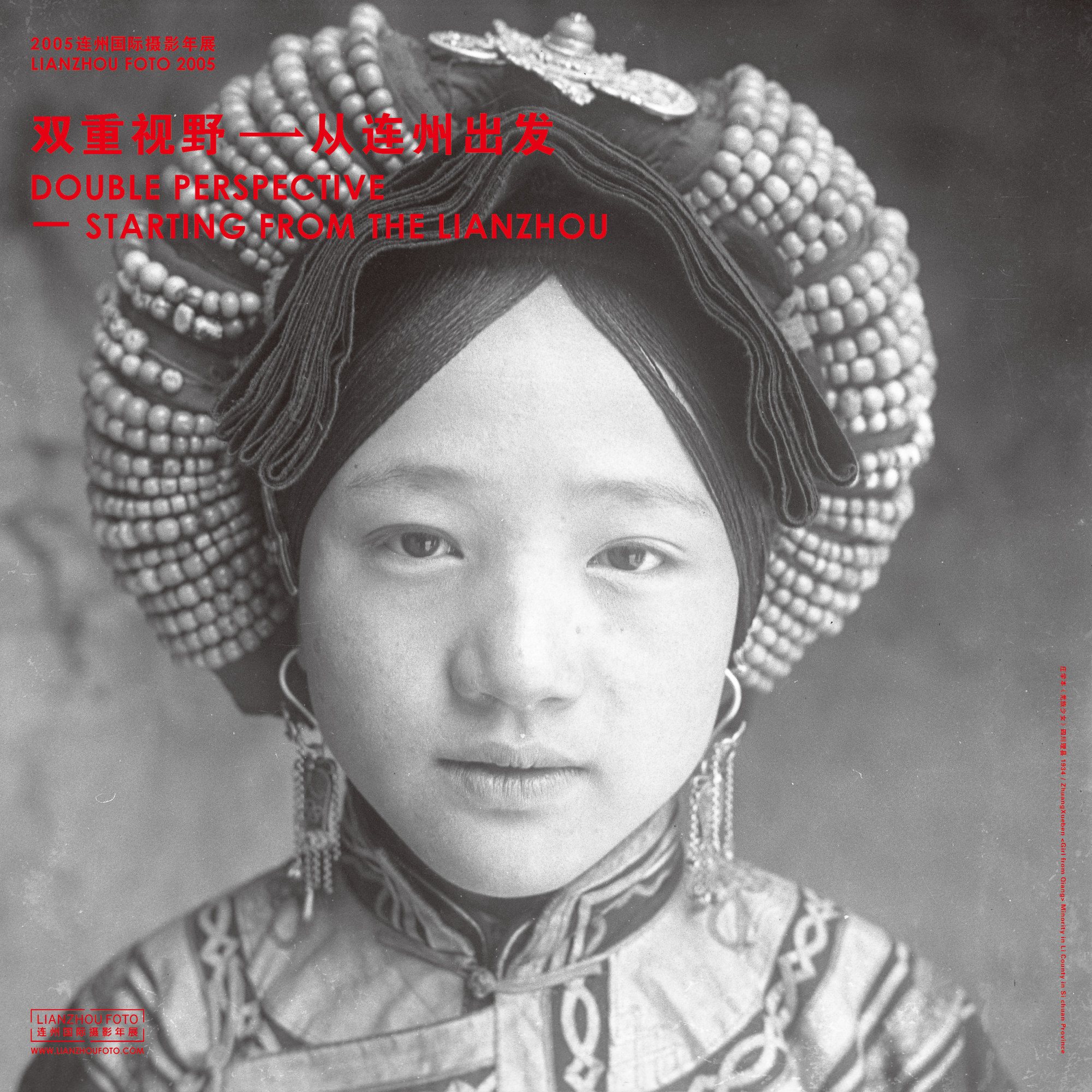

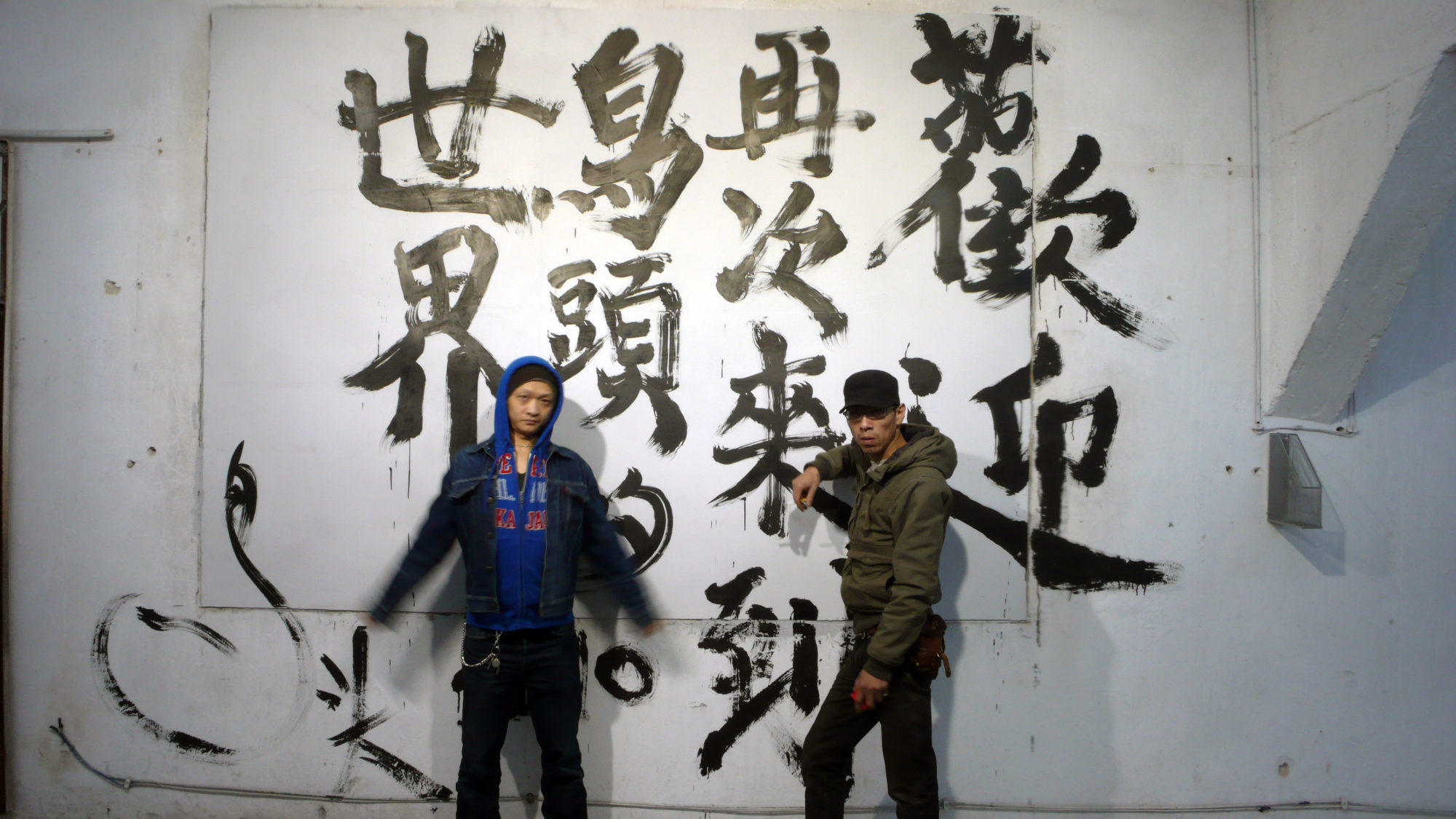

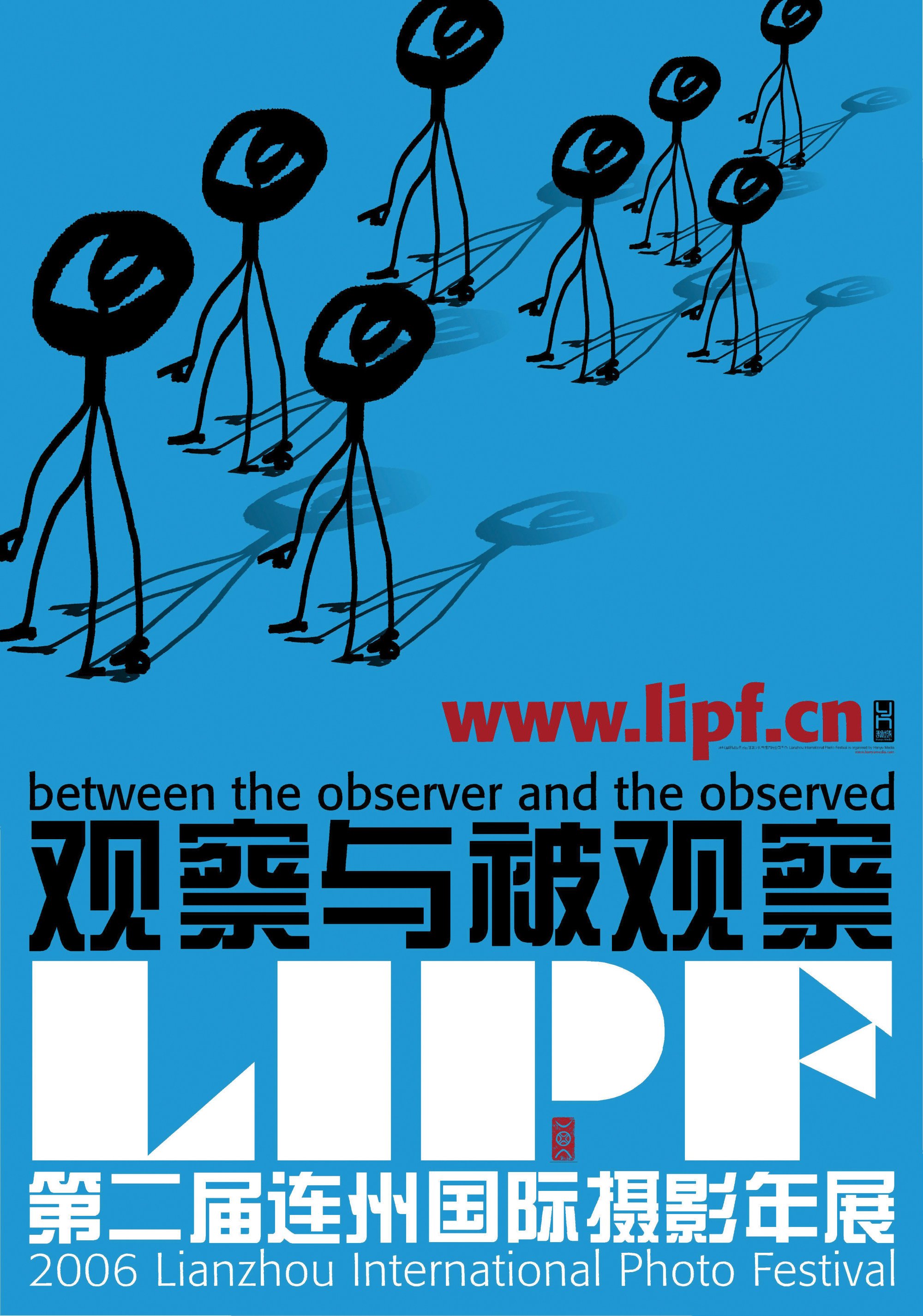

For Shanghai-based art collective Birdhead, consisting of Song Tao and Ji Weiyu, the first edition of the festival, “Double Perspective”, was, as the curational title suggests, quite a yin-yang experience.

“Getting from Shanghai to such a poor county town somewhere in the mountains of the south wasn’t easy,” recalls Song. “It was like time-travelling back to Red China. But it was really rewarding.”

Birdhead had formed just a year earlier, in 2004, part of a radical generation of artists using photography to “digest and apply the thinking mode of conceptual art into the context of image interpretation”, as their manifesto worded it.

“We wanted to use photography like a writer uses words or a musician uses notes, to say something,” says Song. “We were young, in our early 20s, and we were just setting out as artists.

“You have to remember, at the time the internet wasn’t that developed so seeing contemporary photographic work, especially art from overseas, wasn’t easy. In China there was only Pingyao. So to meet French photographers and other people interested in what we were doing was exciting.”

Early editions of Lianzhou were not, however, without their glitches.

“In 2006, the French Ministry of Culture sponsored three exhibitions including a video installation,” recalls Duan. “While we held the opening ceremony, the computer that was being used by the artist was stolen.”

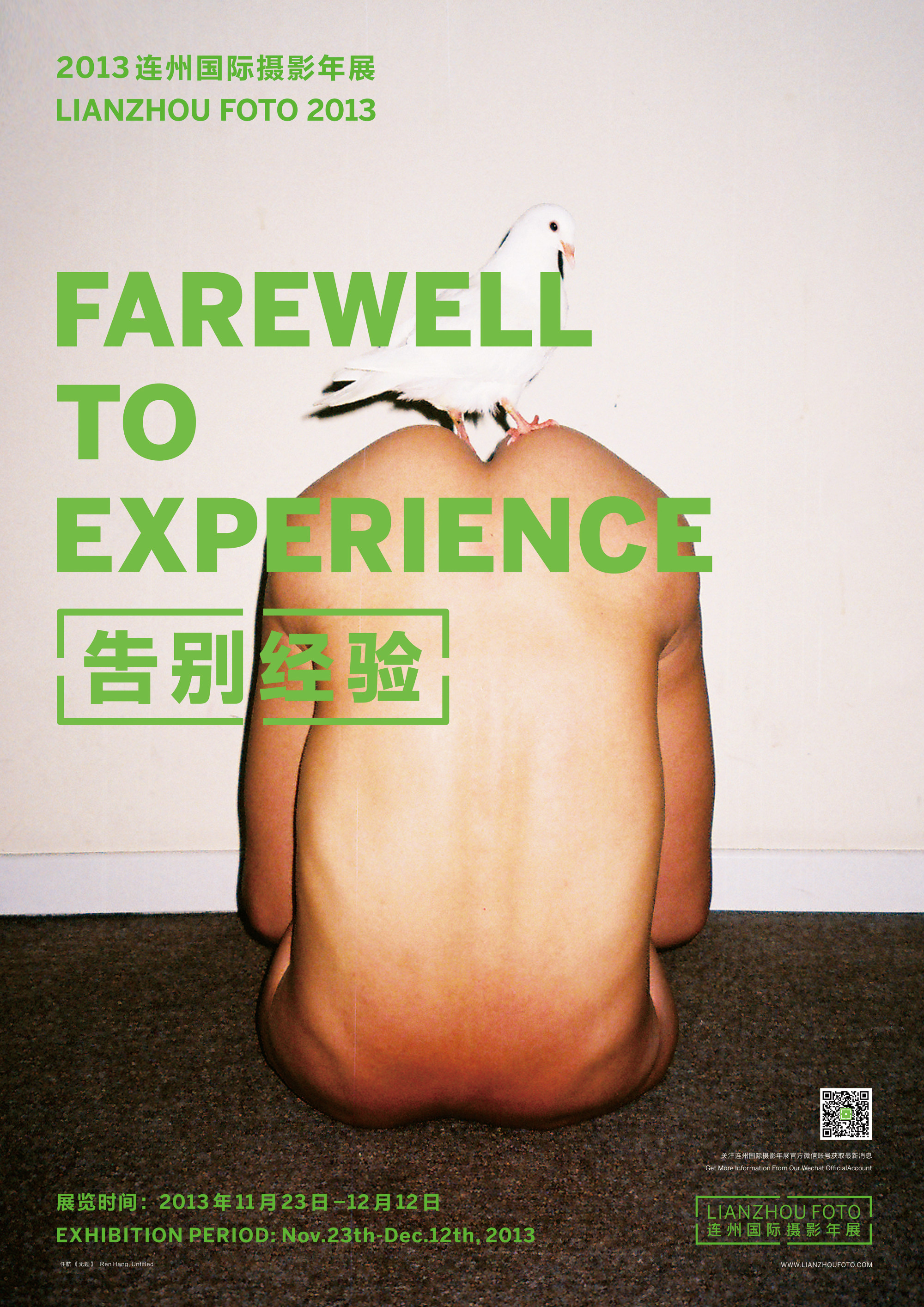

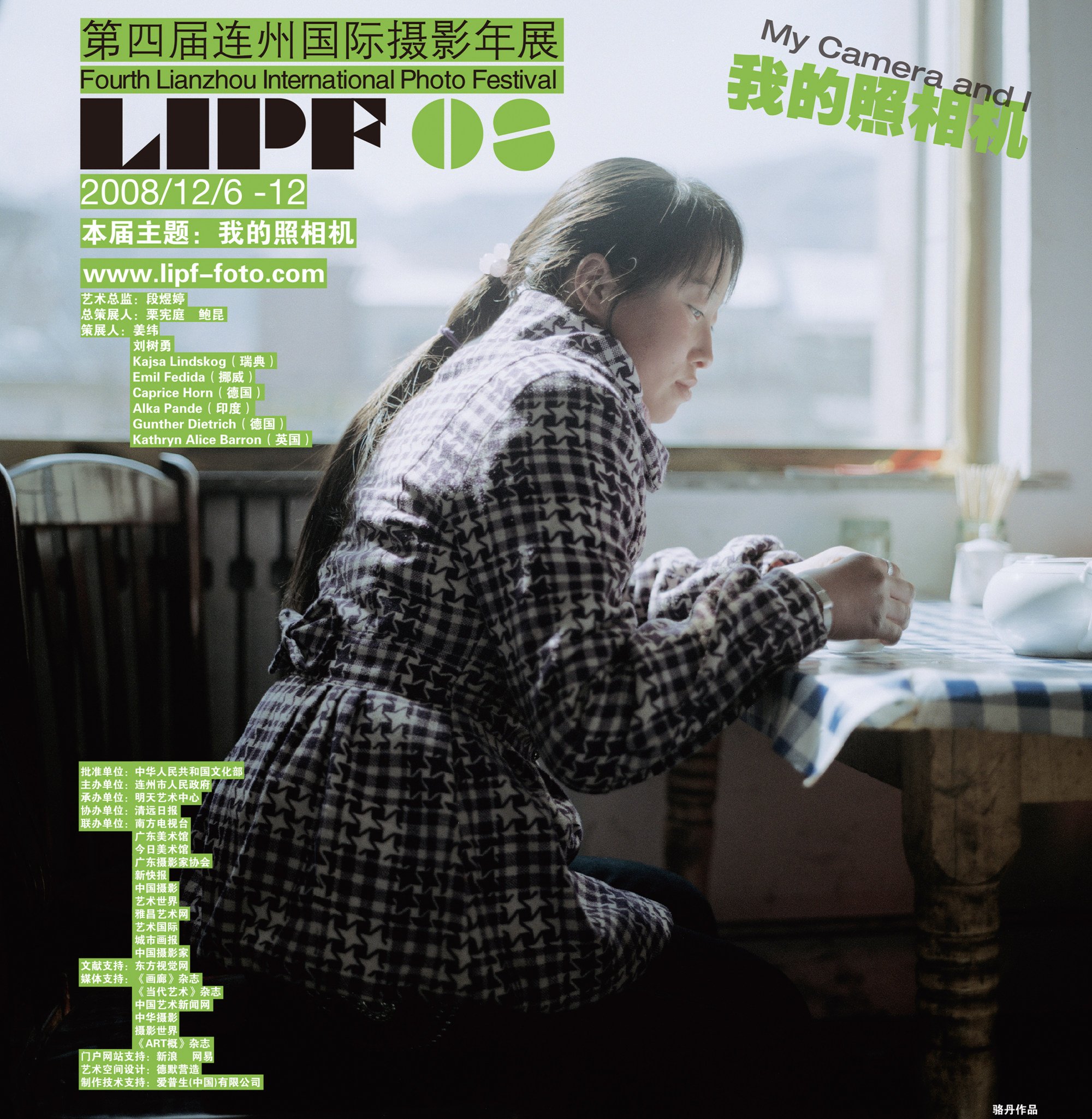

Yet by 2008, Duan felt the festival was becoming truly progressive. “That was a brilliant year as we invited Chinese contemporary art godfather Li Xianting to be a guest curator,” she says. “The festival theme was ‘My Camera and I’.

“He said he wanted to remind us that photography has a power all of its own but we must return to basics, to remember that photography is essentially the world looking at itself.

“That really moved the festival onto a new level and inspired a lot of people.”

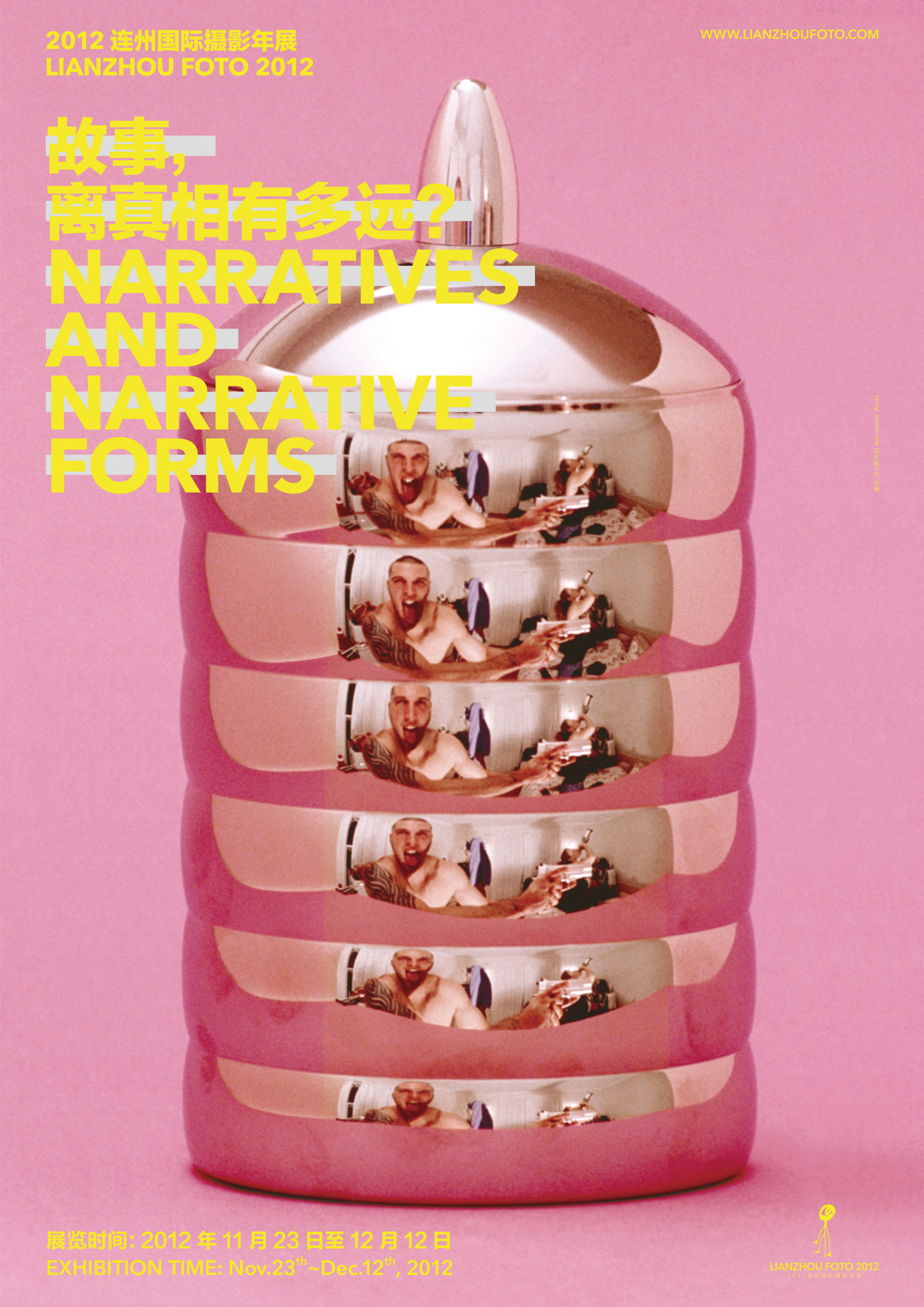

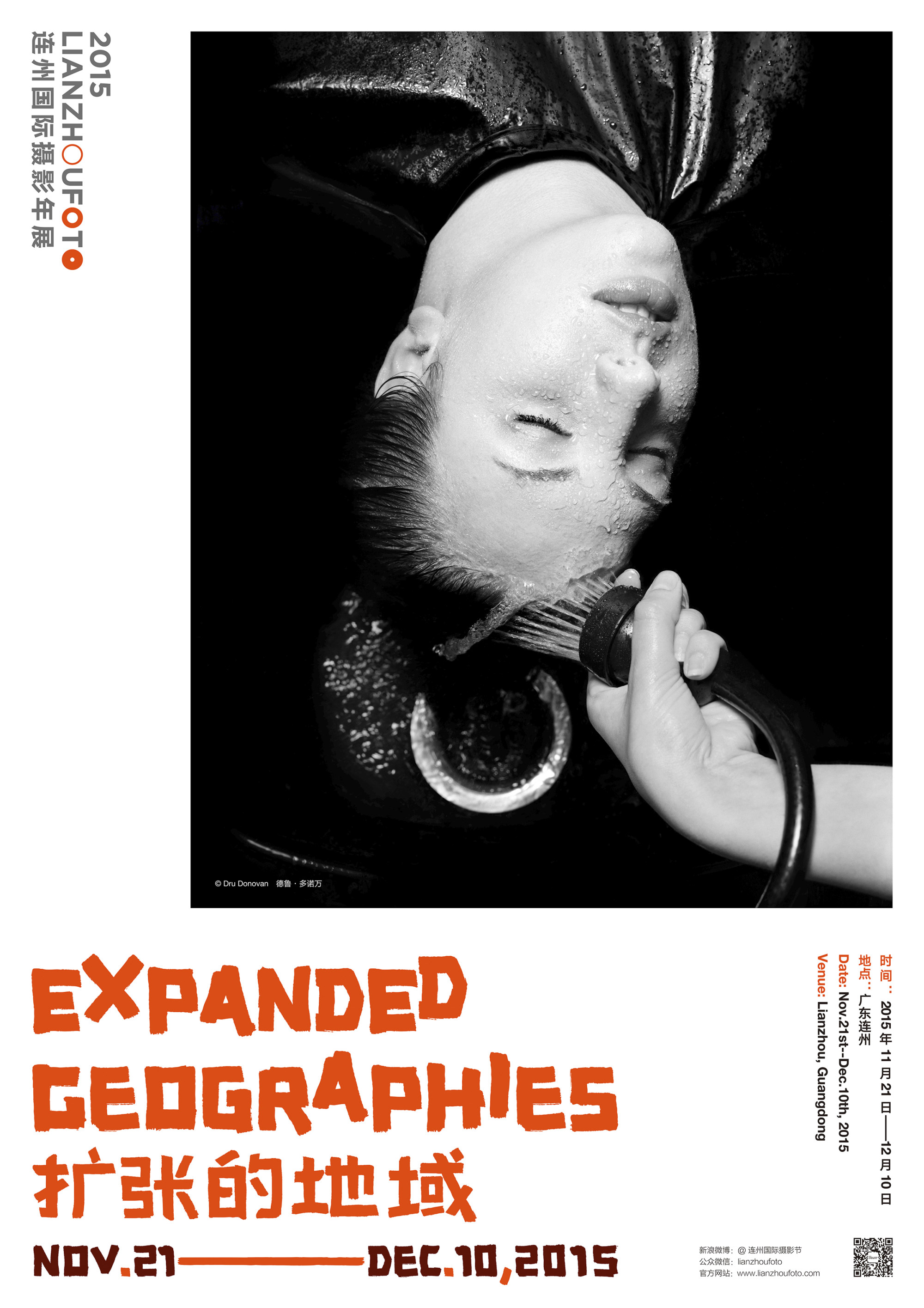

Festival art director Da Men, a photographer from Wenzhou who first exhibited in 2009 in Lianzhou, and later married Duan, looks back on 2010-11 as a turning point in the history of Chinese contemporary photography.

“That’s when you started to see a wave of really good artists using photography as a medium emerging across China,” he says. “And they all came to Lianzhou.”

“We exhibited again in 2010,” says Birdhead’s Song. “Lianzhou had changed a bit. Accommodation was better and by that time the three disused factories, the Granary, the Shoe Factory and the Candy Factory, were well-established as festival sites. What that gave us was space where we could realise the ideas we’d come up with in our studio.”

Both Duan and Da Men cite the two members of Birdhead, who exhibited a total of three times over 15 years, as artists Lianzhou was able to nurture and showcase to the world.

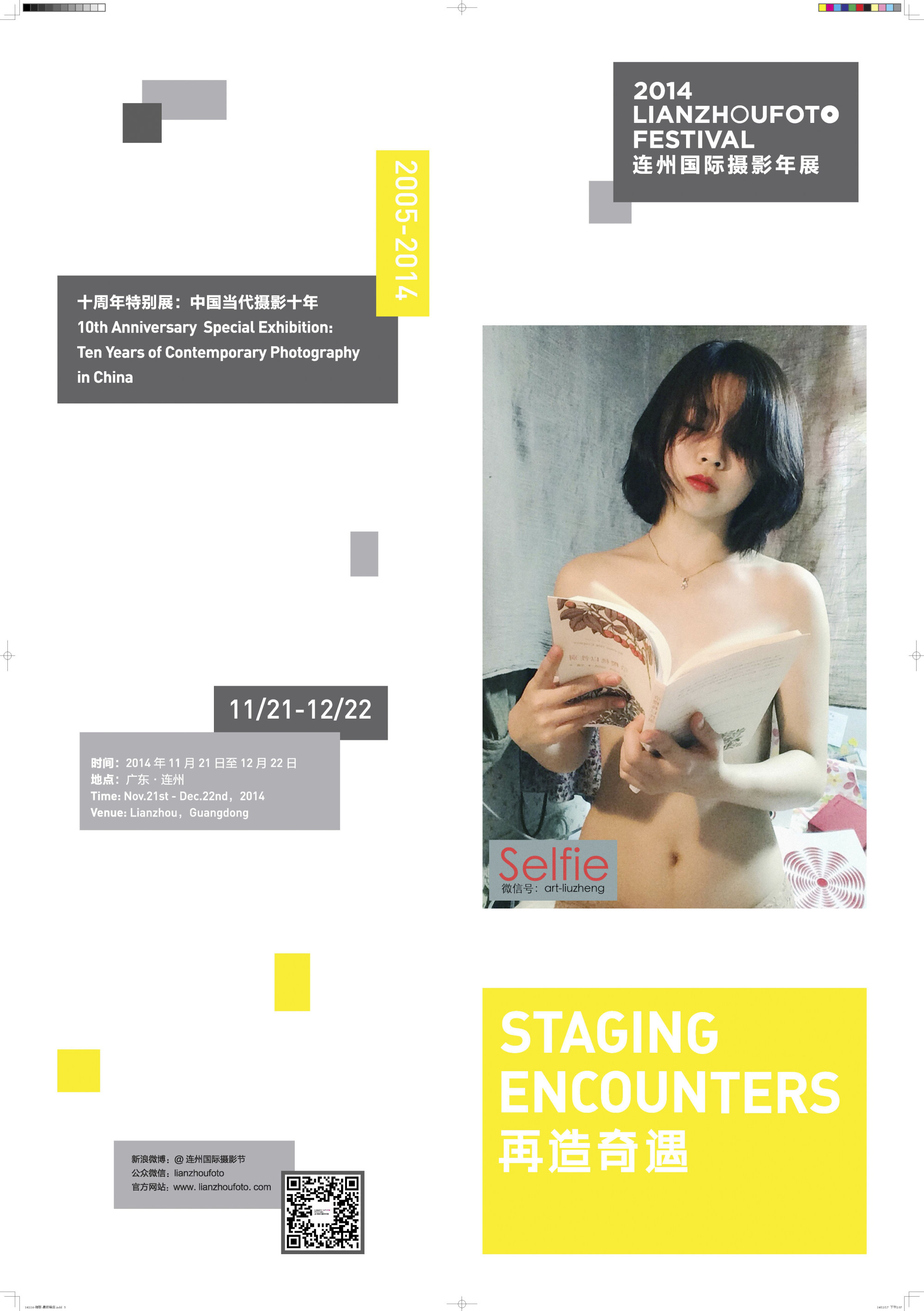

“We exhibited Wang Jiuliang,” recalls Duan of an artist whose work on plastic waste in north China ultimately influenced government environmental policy. “And, of course, Li Zhengde was exhibited, too,” she says, raising an eyebrow at the memory of Chinese photography’s enfant terrible.

Hunan native Li had worked in various professions before moving into the art world. His first series, “The Unseen World”, which captured Shenzhen’s poor neighbourhoods and its downtrodden inhabitants at night, made a ripple but his big splash came with his second series, “The New Chinese”, which documented China’s consumer revolution in all its gaudy glory.

“I was aware of Lianzhou from around 2006 but I didn’t make it up there until 2010,” says Li. “I arrived sometime after the opening week and it was really quiet. The food was delicious, as I recall, fusion food – Cantonese cuisine garnished with chilli peppers from Hunan.

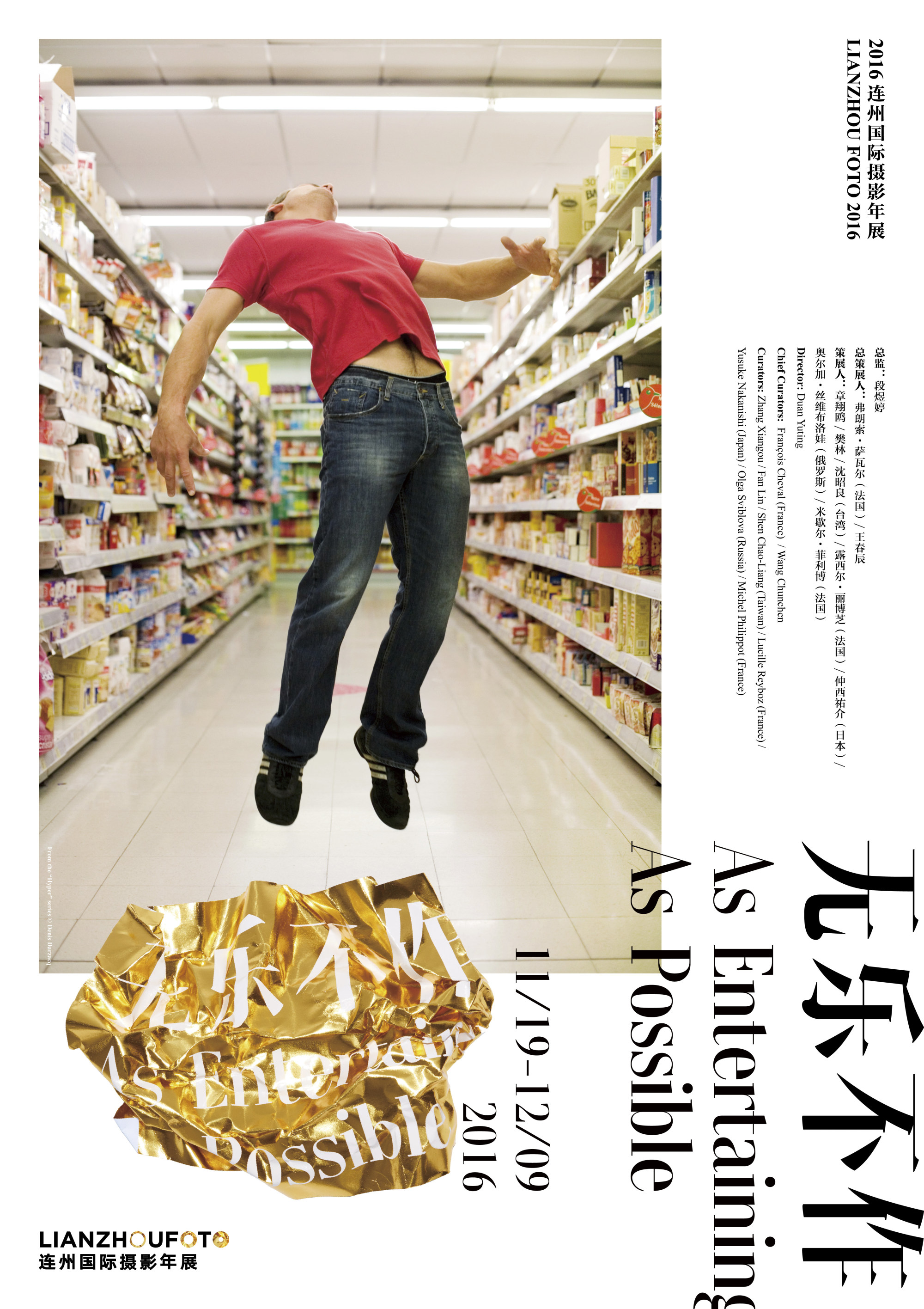

“After lunch, I remember having to turn the lights on and off in exhibition halls as there was no one around. But the work on display really impressed me. I went there three times after that and my photographs were exhibited twice, in 2014 and 2016.”

Li applied street photography techniques while moonlighting as a camera-for-hire at corporate events in Shenzhen when making “The New Chinese”, a satirical, black-humoured series that raised pertinent questions about consumerism-with-Chinese-characteristics. It was not without controversy.

“In China, there’s still a sense that art should be beautiful,” says Li, “but I showed them the opposite.”

You know it’s easy to be a curator in Shenzhen or Beijing, to jet into an established art space. But in Lianzhou you’re doing something directly for the peopleVeteran curator François Cheval

One prominent art critic, Wu Jialin, described the series simply as “rubbish” and one of the images was pulled from a gallery wall in Shanghai. Yet fearless Lianzhou Foto put “The New Chinese” on full display in the Granary, which, Li believes, helped him get the work exhibited in Europe and eventually made into a book published by Stairs Press.

“Lianzhou was the most academic and high-quality photography festival in China,” he says.

Slovenian photographer Matjaz Tancic went to Lianzhou three times, from 2014 to 2016. His festival exhibition, titled “3DPRK”, was a similarly emotive series of photographs, shot during several trips to North Korea, and shown in the Shoe Factory: big prints of everyday people in the hermit kingdom experienced with the aid of red and green 3D glasses.

“It was definitely one of the best photo festivals in China,” says Tancic, “with very nice venues like the Shoe Factory and Granary and great curation of the best contemporary Chinese and international photographers.

“The work on display could have easily been on show in Paris, New York or London and not in a small town in Guangdong. It was a great place for getting inspired and networking.”

The standard of excellence was not just down to Duan’s eye for quality photographic artwork but also the alliances she forged at home and overseas, particularly in France.

“Photography as an art form was pioneered by the French,” she says. “Events like Arles and Paris Photo are the most impressive I’ve seen in the world, so it was always important to me to keep a close association with France.”

To maintain Lianzhou Foto’s French connection, veteran curator François Cheval, an anthropologist who had come of age in the “golden age of museums in France during the 1980s and 90s”, and had experience working in places as diverse as Kenya and Réunion Island, was brought on board in 2007. He would be involved in the festival until its last edition, in 2019.

“Duan would travel abroad looking to galleries and festivals, building relationships,” says Cheval. “From the onset we had a good rapport. She struck me as intelligent, professional and open.

“In my mind, I had an idea of China through the images I’d seen of vast urban expanses. But my first impression of Lianzhou, when I arrived, was, ‘Wow, this is deep China.’

“You know it’s easy to be a curator in Shenzhen or Beijing, to jet into an established art space. But in Lianzhou you’re doing something directly for the people. That’s what attracted me to work with Duan on the festival.”

For Cheval, operating in the Nanling Mountains for several weeks a year took some getting used to, but he soon grew fond of the city.

“I walked the narrow roads past the little shops. I would dine each day in my favourite little cafe, which became like a second home. Every year was always a challenge, of course, and we worked long hours, but we finished each edition with a great sense of satisfaction.”

Cheval recalls many highlights over the years but notes Wu Guoyong’s work “No Place to Place”, which captured China’s bicycle graveyards and was exhibited in Lianzhou in 2018, as a series that exemplifies what he wants to see in contemporary photographic artwork.

“With art we are talking about the world, about humanity and the contractions we live with. Wu talks very directly about an ecological disaster but his images have a tender beauty. They are like a 19th century Impressionist painting.”

Cheval, who has managed museums for most of his career, also feels a great sense of achievement in the realisation of the Lianzhou Museum of Photography, which was designed by Guangzhou-based O-office Architects after consultation with Duan and himself.

“I think it is one of the most beautiful museums in the world,” he says. “How it integrates with local architecture, how it blends East and West. I feel that if this is my legacy, it’s enough.”

Cheval considers himself a “missionary” who has always believed “art is the best way to change the world”. So I wonder how he felt when censorship amped-up during the past three editions of the festival, often resulting in art he had commissioned from Europe being taken down.

“C’est triste,” he says, “sad for those who never truly understood the soft power they had. Sad that one monochrome national narrative [is what] they want to convey. I’m sad for the artists and sad for Lianzhou but most of all I’m sad for the way it finished.”

The fact that embattled Lianzhou remains essentially an unfinished story has prompted artists and attendees to continue to speculate over its future.

“It’s such a pity,” says Lianzhou native Tang Ying. “The Photography Museum had just been built, so I don’t want to see it stopped. Some people say it could be changed to an online exhibition but I don’t think that would work.

“At Lianzhou, everyone comes together because of the thing they love – to experience the photographic work up close, to communicate face to face, and to engage with one another.

“Every Lianzhou citizen is proud of the festival whether they know about photography or not. You can see that in the people who used to play cards and chat in the alleys who can be seen walking around the museum.”

Even Duan can’t answer the question at the moment. She explains that “when we opened the museum, in 2017, we were severely scrutinised and some of the work we’d commissioned could not be shown, 2018 and 2019 were worse. Things kept getting changed last minute and I felt my voice was no longer being heard.”

However, Duan is not willing to abandon a project that is so wedded to her identity she describes it as, “who I am, not what I do”.

“The question is not will Lianzhou return but will it be like the Lianzhou of the past? This is what everyone is asking. I would say that if we can give artists creative space and the freedom to express themselves then I will curate it again. But without that freedom there can be no art.”