- Siti Aisyah recalls how an innocent prank went horribly wrong, ending in murder and and landing her in jail

- ‘At the police station they told me I had been involved in the murder of a president’s brother. I laughed and said: You are joking’

The star-struck young woman blushes with delight as the filmmaker leans in close, confiding that “if today goes well, you’ll be known all around the world. You can become a famous actress”.

Her new job was to go up behind strangers at various locations around the Malaysian capital and smear baby oil on their faces while the film crew recorded the targets’ bemused reactions from a distance. She was paid 500 ringgit (US$119) for each “hit”.

Siti was told the oddball pranks were being edited into YouTube broadcasts, and the producers overseas were so impressed by her performances they were considering flying her to America.

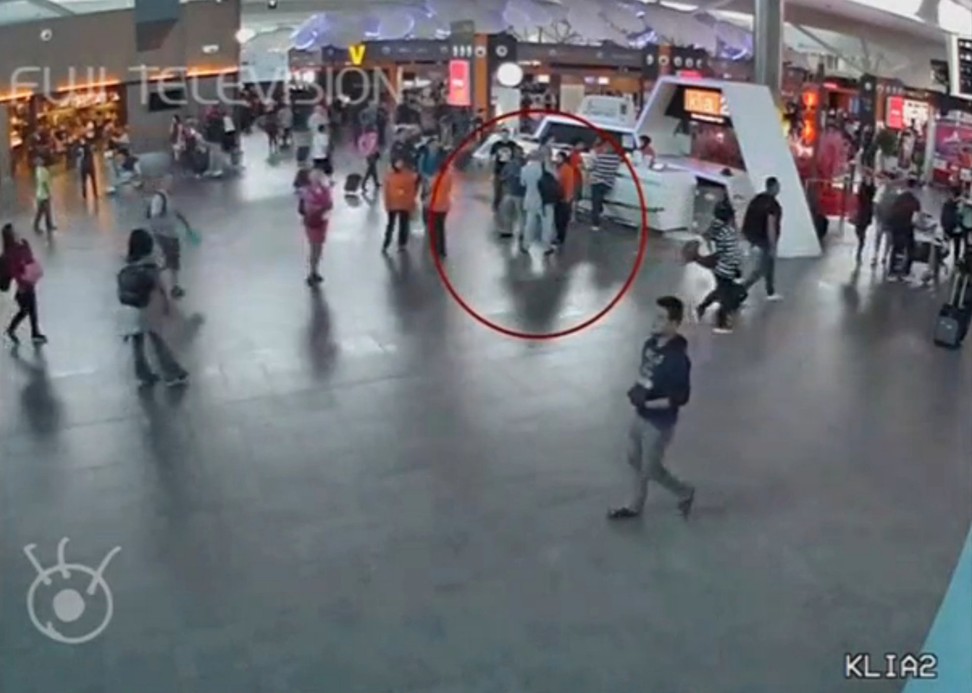

But first there was one final prank to perform. In February 2017, the target was a mystery VIP checking in for a flight from Kuala Lumpur International Airport and, this time, Siti would carry it out with another actress, set to approach from another direction.

As with each prank, the filmmaker produced a small, transparent bottle, poured its liquid contents onto Siti’s palms, pointed out her target in the busy departure area and sent her off in his direction.

Siti, oblivious to the horror unfolding nearby, would spend three hours ambling happily around the airport, buying clothes and having lunch before returning to the hotel where she worked as a masseuse between filming assignments.

I had no idea what I had done. They told me they were going to make me a star. I feel so foolish for believing them and believing them so easilySiti Aisyah

Siti, now 27, is back living in her parents’ single-storey home in a small, dusty village outside Serang, Java, where her father, Hasan Asria, 54, makes a modest living selling tamarind and other spices. Contented, relaxed and something of a celebrity in her hometown, she has lost the haunted, gaunt appearance of her days in a Kuala Lumpur prison and gone from 49kg to 62kg since her release.

A naive country girl who left school at 12, and whose only previous knowledge of either Korea was through K-pop, Siti is an unlikely political assassin.

“I had no idea what I had done,” she says. “They told me they were going to make me a star. I feel so foolish for believing them and believing them so easily.

“I feel bad about what happened to Kim Jong-nam and I wish I had never been involved. If I could turn back time, I would never have agreed to do any of it, right from the start.”

Siti’s accidental entanglement with the North Korean regime’s killing machine began in the early hours of a January morning in 2017, when she was approached by a Malaysian taxi driver as she left the sleazy Beach Club Cafe, in Kuala Lumpur.

Separated from her husband and son after marrying at 16 and giving birth at 17, Siti was one of thousands of young women from poor parts of Indonesia lured into making a shadowy living in wealthy Kuala Lumpur, where she worked as a masseuse in the notorious Flamingo Hotel. Since her arrest, the hotel’s massage parlour has been shut down.

“The taxi driver told me he had a Japanese client looking for someone to act in a reality TV show, and said I had just the right look,” she says.

Flattered, Siti went to an upmarket shopping mall the next day where she met “James”, a chisel-jawed 30-year-old who told her he was a Japanese television producer making Candid Camera-style shows for YouTube. In fact, he was a North Korean agent named Ri Ji-u.

He paid her the equivalent of US$95 to approach three random men in the mall, grab their hands and smear baby lotion on them, then apologise and walk away while he filmed it on his iPhone.

“One of the men asked me for my number after I did it to him,” she giggles. “James told me I had done a good job and there would be more work like this for me.

“I was very happy. I had earned 400 ringgit for 15 minutes’ work. In the hotel where I worked as a masseuse I earned only 20 ringgit for each customer.”

In the following weeks, Siti was summoned by James to carry out similar pranks in other malls, as well as at Kuala Lumpur airport. Each time, he put lotion on Siti’s hands before she smeared her victims’ faces from behind. The bemused targets were usually too confounded to react. Siti would apologise and quickly exit the scene.

“James told me he would take me to America,” she says. “He said, ‘You are working very well. Would you like to do this in Singapore or the USA?’ I said yes, of course, and I gave him my passport so he could arrange visas for me. I was very excited. I thought this was going to change my life and I would be able to leave my old life behind.”

Now earning 500 ringgitfor each “prank”, Siti was developing feelings for James, with whom she communicated using Google Translate, as he spoke no English or Bahasa Indonesia. “I liked him because he was handsome, but he was shy around women. It made him more interesting,” she says.

Siti would soon be passed from one agent to another, however, when she was flown to the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, to carry out a prank at the airport where the North Koreans apparently had information that Kim was due to pass through.

In Phnom Penh, James introduced Siti to her new handler, Mr Chang – another North Korean agent, whose real name is Hong Song-hac – who spoke fluent Bahasa Indonesia. Kim, however, changed his travel plans and Siti instead carried out two more pranks on strangers for a payment of nearly US$600.

Siti continued to participate in filmed pranks in Kuala Lumpur and at one stage was given money to buy a plane ticket to Macau – one of Kim’s long-time favourite ports of call – before that trip was aborted, apparently because of another change in his travel plans.

Chang, 35, was sterner than James.

“I didn’t like him,” says Siti. “He told me, ‘I like joking around but when it comes to work, I am very serious.’ When he got serious, I was a little bit afraid of him. He asked if I wanted to make my parents happy and said that if I did, I had to work hard and be serious.”

She admits she had doubts about the work at times.

“I did question it, but James told me, ‘This is for a big Japanese company and this kind of thing is very popular there.’ I believed him and I was very happy about the money I was getting.”

Kim Jong-nam’s accused killers: North Korean puppets or cold-blooded murderers?

A fortnight before the assassination, Siti returned home to Indonesia to see her parents and her 10-year-old son.

“I told them I had a new job doing pranks for TV and that I might be going to America. My mother said, ‘Don’t move too far away,’ and I told her, ‘It’s OK because I won’t be alone. People will look after me.’”

By now, the cat-and-mouse game was nearing its conclusion as the North Korean agents closed in on their quarry, tracking Kim as he returned to Malaysia and met a CIA agent in a Langkawi hotel, where he exchanged a laptop full of data for a wad of US$100 bills before heading to the capital.

The encounter, monitored by North Korean agents, would have undoubtedly fuelled Kim Jong-un’s fears that the United States planned to topple him and install his hapless half-brother as a puppet leader.

Siti returned to Kuala Lumpur where, two days before the assassination, Chang surprised her by giving her a US$200 bonus.

“When I asked what the money was for, he said, ‘It is because you worked very well in Phnom Penh and my boss is very happy with you,’” she says.

I didn’t really believe I was going to be famous, but I liked the money. I was thinking only about the moneySiti Aisyah

Siti belatedly celebrated her 25th birthday with friends at the Hard Rock Cafe in Jakarta the following night, telling them excitedly about her new line of work. “Siti is going to be a celebrity,” one of them says in a prescient clip captured on her phone at what turned out to be the last time many of them would see her.

She partied hard and turned up an hour late at Kuala Lumpur airport the next morning. Chang, who was waiting calmly at a coffee shop, briefed her on the shoot he promised could propel her to international stardom.

“I didn’t really believe I was going to be famous, but I liked the money,” says Siti. “I was thinking only about the money.”

After a wait of some 90 minutes, Chang told her their target was approaching. He put the liquid on her hands and pointed her in his direction as he stood back, phone at the ready to record it.

“Mr Chang told me the man was a big boss in his company,” she says. “He said he was very arrogant and might get angry so I should carry out the prank and then get away as quickly as I could.”

Siti walked nervously towards Kim Jong-nam as he prepared to check in for his flight to Macau, ready to put her hands to his face from behind. She was just two steps away from him when, she says, Huong suddenly cut across her path from a different direction, and placed her hands over his eyes. Siti froze.

“He looked annoyed and upset,” says Siti. “He looked rich and was clearly angry. I thought he might report us to the police. I was scared and I ran away.”

Siti and Huong fled in separate directions, heading to different washrooms and, in an act that almost certainly saved their lives, washed the sticky liquid off their hands.

Two nights later, when police arrived at the Flamingo Hotel to arrest her, Siti assumed it was a routine round-up of foreign workers.

“Three police officers came in and there were others outside,” she recalls. “They said, ‘Where were you on the 13th? Were you at the airport?’ I said, ‘Yes, I was shooting a video.’ They asked why I didn’t ask for permission and said, ‘Come with us to the police station.’ I said OK because for me it was just a police check.

“At the police station they told me I had been involved in the murder of a president’s brother. I laughed and said, ‘You are joking,’ and asked them to give me my passport and my phone and let me go home. Then they got angry with me and handcuffed me.”

“I was terrified when I realised I might be executed,” she says. “I was so confused. I cried every day for three months. I couldn’t eat and I couldn’t drink.”

She was kept in isolation with only the Koran to read for the first year of imprisonment and a weekly 15-minute phone call to her family. “The first time I called my parents, I just cried,” she says. “My parents have never asked me about the case. They’ve seen it on TV news so they know what it was about. But they don’t want me to think about what I’ve been through. They don’t want to add to the burden.”

Her only company apart from visits from her lawyer and embassy officials was the prison guards. “There was always a guard in front of my cell. They worked in three shifts, 24 hours a day,” she says. “They thought I was a North Korean agent. They asked me if I wanted to commit suicide because it was such a big case that I was involved in. Another time, one of them told me that if I didn’t plead guilty, North Korea would bomb my home country. I didn’t know whether to believe it or not.”

She found it hard to come to terms with the way in which James and Chang had deceived her. “They were nice to me and I told them so many personal things. It’s awful to think they put deadly poison on my hands without any thought of what it might do to me.”

It was only when she was released this March, more than two years after the assassination, that the enormity of the case dawned upon her.

“I didn’t know who Kim Jong-un was before all of this. I didn’t even know where North Korea was,” she says. “When I got out of prison, I looked up my name on YouTube and realised what it had all been about. I thought, ‘How can I have been caught up in such a big murder case involving these important people? I am just a girl from a small village.’”

Siti was treated like a VIP upon her release, flown home with Indonesian government officials on a tycoon’s private jet and taken straight to see President Joko Widodo. She had achieved the celebrity she craved but at a terrible price.

Her most emotional moment was the reunion with her son, Rio. “My former father-in-law brought him to see me. He asked me to pick him up like I used to, but he had grown so much I couldn’t pick him up any more. We had been apart for more than two years. I told him I was so sorry and I hadn’t been able to contact him while I was in prison. He just smiled and hugged me tightly.”

They lived because they were able to wash their hands within 15 minutes. The skin on your palm is thick so it is more difficult to penetrateGooi Soon Seng, lawyer for Siti Aisyah

Siti’s lawyer, Gooi Soon Seng – who had criss-crossed Asia building up a dossier of evidence to show his client was an innocent pawn in a meticulously planned political killing – had mixed feelings over her release. He was delighted she was free but disappointed that he would not get the opportunity to expose in court what he says was a state-sponsored assassination.

“It was a brilliant plot when you think about it,” Gooi says. “They must have come up with it after considerable thought. If it had gone to plan, Kim Jong-nam would have died on the plane. It would have been classified as a heart attack and everything would have gone unnoticed.

“They weren’t worried about the two girls. They didn’t know anything about the plot so they could never have exposed them. And they weren’t bothered about whether the girls lived or died. They didn’t tell them to wear gloves or wash their hands afterwards. They washed their hands straight afterwards only because they were oily.

“According to experts I spoke to, they lived because they were able to wash their hands within 15 minutes. The skin on your palm is thick so it is more difficult to penetrate. But when Huong put the liquid on Kim Jong-nam she put it around his eyes and that area is much more permeable. That is why he died within half an hour.”

Gooi is adamant that the real killers should be punished. “They brought VX into the country – that is tantamount to a declaration of war,” he says. “And an innocent life has been taken away. The people who planned this murder should absolutely be brought to justice.”

For Siti, in her home village, there are more mundane matters at hand, such as taking online lessons to become a beautician as she looks to start her life over again.

“I want to work in a beauty salon in Jakarta,” she says. “I don’t want to go back to the work I was doing in the past. I want a better future. That way, maybe my son can come live with me.”

The notoriety of her ordeal still haunts her daily life. “In the village, people sometimes joke with me and say, ‘You’re a celebrity now.’ When I go to the market in town people come up to me and say, ‘You’re Siti Aisyah.’”

As she stands outside the school she left at the age of 12, immaculately dressed, manicured and looking somewhat incongruous to the conservative rural village where almost every other woman wears a hijab, Siti still seems strangely seduced by the fame that found her in the deadliest of circumstances.

“Who would imagine that someone like me, who only went to primary school, could become world famous?” she asks with a sly but unmistakable hint of pride.