Grubby reality eclipses Ove Arup’s soaring achievement

Company founded by the 20th century’s most admired engineer had a hand in iconic buildings the world over, including Hong Kong. It’s present-day dealings in the city, and elsewhere, would have Arup spinning in his grave

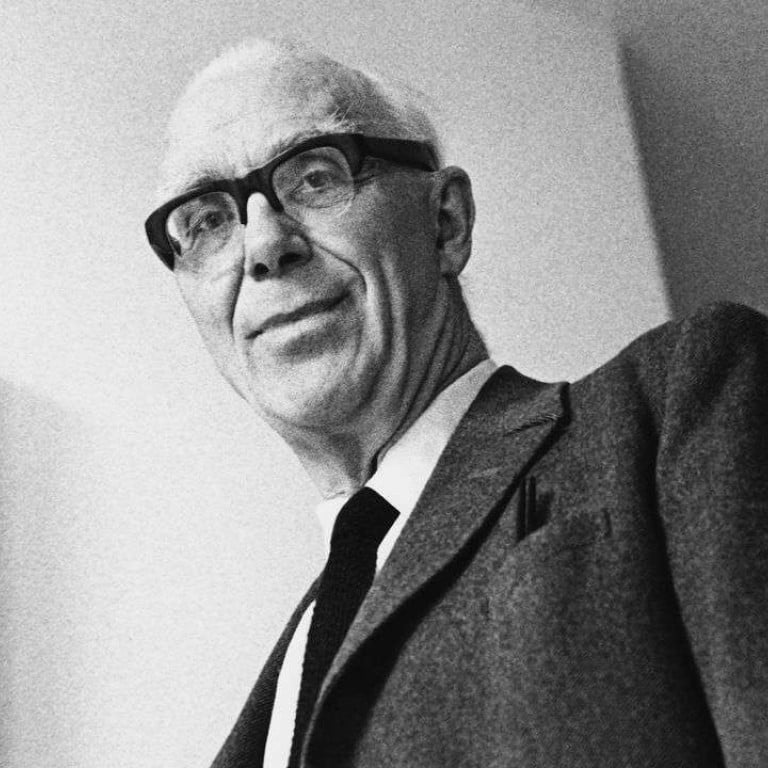

The most influential and admired engineer of the 20th century – who embedded his core values in the pioneering consultancy firm he founded in London in 1946 – must be turning in his grave.

Sir Ove Arup was that rare combination of philosopher and visionary structural engineer. His name and his principle of “total design” are embedded in some of the world’s most iconic buildings, including the Sydney Opera House, the Centre Pompidou, in Paris, and HSBC’s Hong Kong headquarters, at 1 Queen’s Road Central.

“Much like the legendary Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Ove Arup was a game-changer who transformed engineering practice in his day,” says Zofia Trafas White, co-curator of an ongoing exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) celebrating Arup’s life (he died in 1988, at the age of 92) and legacy in what he called the “built world”.

As if to underline the Hong Kong connection, the exhibition, titled “Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design”, features a large-scale model of the HSBC building as a prominent exhibit.

“Unconventional and playful in his approach, his collaborative working style revolutionised building design during his lifetime and influenced how buildings are made today,” White says.

Inexplicably, “the greatest engineer of the 20th century”, as White calls him, never enjoyed the same public profile as his contemporaries in architecture, the arts and science. All of which makes it particularly unfortunate that his name should be sullied by recent media reports just as he was receiving some well-deserved recognition.

The challenge for leaders at Arup today is to embody the values Ove set out in a way that makes sense to each of them

This year, the eponymous company he founded celebrates its 40th anniversary in Hong Kong, where it has made a major impact on the city’s skyline and urban fabric, from the tallest building (International Commerce Centre) to the longest cable-stayed bridge (Stonecutters). Unfortunately, celebrations have been muted following reports linking Arup Hong Kong to the ongoing Wang Chau housing development controversy.

The company has been accused of including confidential government information in planning applications it made on behalf of client New World Development, as part of the developer’s bid to build luxury homes next to a government project in Wang Chau. Arup was hired to provide consulting services to both the government and New World on housing projects in the district, a part of Yuen Long.

The commercial and legal implications remain unclear but it is a public relations disaster for a firm that employs more than 12,000 people in 92 countries. On September 28, Secretary for Development Paul Chan Mo-po, himself no stranger to controversy, launched an official probe into the affair.

Hong Kong development minister launches probe into possible breach of confidentiality over Yuen Long leaks

According to the government’s own information, the Civil Engineering and Development Department awarded two major contracts to Arup this year, worth more than HK$38 million. The Environmental Protection Department’s published list of “Consultancies awarded in the past six months” shows 60 per cent of all its consultancy projects, worth about HK$69 million in total, were granted to Arup. Since January 2012, 45 per cent of all Planning Department contracts have gone to Arup, totalling more than HK$126 million. The Highways Department has two outstanding contracts for the Hong Kong Link Road, worth HK$21.7 billion, both involving Arup as resident engineer. And when the government wanted a consultant to investigate its recent “smart city initiative”, the obvious candidate was ... yes, you guessed it ... Arup.

Think of any current large-scale local infrastructure project – the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link, the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau bridge, the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Western Corridor, the extension of the MTR’s West Rail line, West Kowloon Cultural District – and the chances are Arup is involved. And, of course, the company has many prestigious private-sector clients, so the questions of potential for ethical compromise, data sharing across projects and professional conflicts of interest arise.

However, it’s not just in Hong Kong where Arup has been under scrutiny.

In October last year, The Guardian newspaper reported that campaigners in London planned to submit a formal complaint to the Metropolitan Police over allegations of “malfeasance in public office” regarding then mayor Boris Johnson’s decision to award Arup, which is headquartered in Britain, and designer Thomas Heatherwick contracts for work on a proposed garden bridge across the River Thames. According to campaigners objecting to the High Speed 2 rail link in Britain, Arup was the only commercial firm that then prime minister David Cameron mentioned in a key infrastructure speech in 2012, and the company’s senior staff had exclusive meetings with senior Tory politicians before being awarded a series of contracts worth £22 million.

ARUP, THE MAN, was born in Newcastle, northern England, on April 16, 1895, to a Danish veterinarian father and a Norwegian mother. He was educated in Germany and Denmark, where he studied philosophy and mathematics before progressing to engineering. In 1923, he returned to England, where he would live for the rest of his life.

Having been involved in the design of air-raid shelters during the second world war and the innovative protective fenders used during the D-Day landings, he struck out on his own at the age of 51. With an initial capital of £10,000, he founded Ove N Arup Consulting Engineers, which in its first year had a turnover of more than £3,300. By 1988, the year of his death, that figure had exceeded £100 million and, in 2015, the firm’s turnover was reported as £1.13 billion.

According to the company, “The results reflected a positive performance from Greater China (mainland and Hong Kong), with a similar upward trend shown across our other regions.”

Arup was closely associated with modernist Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus school, and he initially came to prominence with his radical design for the Penguin Pool at London Zoo, with its distinctive concrete spiral ramps.

For better or worse, Arup became known as the man who could work magic with reinforced concrete. He developed the concept of “total design”: the functionality and liveability of a structure was designed in from the start. This called for a more collaborative approach to projects, one in which engineers, builders, planners, architects and end-users were involved from day one. A new generation of leading lights of architecture beat a path to the doors of Arup’s young firm, knowing that, with his expertise and support, their ambitious visions were more likely to be realised.

“This endlessly doodling, whimsically rhyming, cigar-waving, beret wearing, accordion squeezing, ceaselessly smiling, foreign sounding, irresistibly charming, mumbling giant: Ove Arup who changed the assumptions of architects and engineers throughout the world,” is how his biographer, Peter Jones, describes him in the book Ove Arup: Masterbuilder of the Twentieth Century (2006).

Having lived through two world wars Arup thought deeply about morality, which was intrinsic in his professional life.

“I wish someone would write a manifesto or declaration not so much of human rights as of human duties or human values, a guide to behaviour to which all men of goodwill, all with a social conscience and an interest or faith in humanity in all countries could subscribe,” he once wrote.

It was the Sydney Opera House project “that propelled the name of Arup onto the global stage”, writes Jones. Many are familiar with the iconic building but not with the prolonged, controversial, costly and discordant aspects that plagued Arup’s Job No 1112.

"Without Ove Arup & Partners, there would be no Sydney Opera House,” wrote Michael Baume, in The Spectator magazine, in 2013, and it proved to be a severe test for the “total design” concept.

In 1957, young architect Jorn Utzon won the competition to design the Opera House and it was Arup who wrote to his fellow Dane offering his help on the project, which was gladly accepted. Utzon’s concept of a roof formed of interlinking “shells” was stunning but impractical; his original charcoal sketches are on display at the V&A exhibition.

“The problems posed by the winning design drawings were now becoming dramatically apparent to almost everyone: they were unusually sketchy, lacked all measurements and had been submitted in the absence of any engineering advice,” writes Jones.

Neither Utzon nor anyone else had the first clue how the Opera House might be built as a functional arts building and, more importantly, no one knew how the distinctive roof could be constructed so it would not collapse in the first strong wind. This became the task of Arup’s senior engineer, Jack Zunz, supported by the great man himself.

The project was scheduled to be completed in four years, with a budget of A$7 million. It would be 14 years before the Opera House opened, in 1973, and it cost more than A$102 million. But while discord, escalating expenditure and public scrutiny put great pressure on his team, Arup insisted that ethics could never be compromised.

“We have a duty to our clients,” he told colleagues. “We must not be party to deceiving the clients in any way.”

While Utzon is rightly applauded for the iconic design, he had resigned from the project years before it was complete and it was Arup and his team who eventually found a way to construct the “shells”.

“I dare say it is one of the most difficult engineering jobs the world has seen,” Arup said.

By this time, Arup took little interest in big projects. The Kingsgate pedestrian bridge, which spans the River Wear in Durham, northern England, and was completed in 1963, is considered to be the last quintessentially Ove Arup project he personally supervised; his original drawings are part of the V&A exhibition. Wishing to avoid scaffolding, he built the bridge in two symmetrical halves, one on each bank of the river, and cantilevered them together. The two halves pivoted on revolving cones, their meeting point marked by an understated bronze expansion joint. The operation to join the two halves took less than 40 minutes. He was the first person to walk across it and he considered it his greatest work.

By the time Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano won the competition to design the “evolving spatial diagram” that was to be Paris’ Centre Georges Pompidou, in 1971, Arup’s firm was an international engineering powerhouse. The young, unknown architects had a small office with just 11 staff, so they were heavily dependent on Arup to deliver the project. As in Sydney, the architects won all the plaudits but the Pompidou could not have been built without Arup’s engineering expertise and the careful implementation of “total design”.

The aim of making money […] it is an aim which if overemphasised gets out of hand and becomes very dangerous for our harmony, unity and very existence

In July 1970, Arup delivered what came to be known as his “key speech” to his partners and employees, assembled from offices around the world for the company’s silver-jubilee event in Winchester, southern England. He sought to outline his vision and aims for the firm he had founded.

“I will try and explain why I keep going on about aims, ideals and moral principles and all that and don’t get down to brass tacks. I do this simply because I think these aims are very important. I can’t see the point in having a large firm with offices all over the world unless there is something which binds us together,” he said, and he offered a grave warning about making the pursuit of wealth the firm’s primary motivator.

“The aim of making money […] it is an aim which if overemphasised gets out of hand and becomes very dangerous for our harmony, unity and very existence.

“The trouble with money is that it is a dividing force not a uniting force [...] if we let it divide us we are sunk as an organisation – at least as a force for good.”

But since his death and the removal of his Christian name from the company’s corporate identity in 2001, there has been concern that Arup’s moral and philosophical doctrine has been forsaken, or at least subtly airbrushed out of the picture, and with it something profound has been lost.

Of course, it is no surprise that organisations lose an essential ingredient when the founder dies or retires (or, in Steve Jobs’ case, is sacked) from the organisation he or she built from nothing, and in November 2011, prompted by the recent death of Apple’s Jobs, Arup’s group head of resourcing and development, David MacDonald, provoked an online discussion with Arup staff about leadership. The responses from employees around the world were not encouraging.

“In my respective region the vision does not resonate with the actual behaviours in the firm,” posted Jetame Poonan, from the South Africa office. One contributor commented that the values of Ove Arup were nothing more than a “fairytale” and another questioned, “Was it really ever there or it had (and still has) been simply a marketing tool, to attract clients and to use or mislead the staff?”

Post Magazine tracked down MacDonald, who is still with the firm, and asked him for his views on the company founder and whether Arup had become detached from his core values. He declined to comment and referred the inquiry to the Hong Kong office, which also declined to comment. In fact, no one at Arup contacted by Post Magazine was prepared to make any comment about Ove Arup, despite repeated requests to both the London and Hong Kong offices.

“Just as Apple had a strong leader in Steve Jobs, Arup had a strong leader in its founder, Ove Arup,” claimed MacDonald, in 2011. “The challenge for leaders at Arup today is to embody the values Ove set out in a way that makes sense to each of them, here and now.”

“Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design” is on at the V&A in London until November 6.