In Taiwan’s capital is a hotel so captivating, the city ‘paused for a moment’ at its unveiling: The Blue has been designed with Emotionalism in its bones

- The Blue in Taiwan was designed as a ‘response to this ever-digitising world’ by pair who wrote a manifesto calling for the Emotional city, not the Smart city

- The art hotel, conceived ‘with Emotionalist principles in mind’, connects people through its spaces: think embedded quotes, exhibitions, a unique shade of blue

Some hotels move you to tears. Some leave you wistful; others blissful. So if you are told your hotel has been designed with buckets of Emotionalism, you might start searching for an adjective.

You will also be missing the point – if only partly.

So when you check into The Blue, in Taipei, you are checking into not just a newly completed hotel, but into a certain way of looking at the world.

Some might say Emotionalism is an unattainable ideal, considering what it is up against. Alternatively, it might just stop us all falling off a cliff.

Among its chief proponents are architect Tszwai So, who grew up in Hong Kong, and architecture writer and editor Herbert Wright, both London based.

What united them, and what has resulted in The Blue, scheduled to open in late April, was a reaction to something with which fans of dystopian science fiction have been familiar for decades.

“I gave a lecture in Krakow, Poland, in 2019,” says Wright, on a joint video call from London with So, “addressing artificial intelligence and what it could do to a city. But obviously the picture has moved on.

“The city is a theatre in which life plays out. And human life is all about emotions, so as artificial intelligence shapes more of what we do, and plays an increasing role in all fields, I thought we needed to do something about it. Many architects come with wonderful emotion in their design approach, but it is in danger.

“In 2020, Tszwai and I proposed [the theme of] Emotionalism for a curatorial bid for the Tallinn Architecture Biennale, in Estonia, for which we were shortlisted,” he says.

“We’re sleepwalking into an algorithm-driven future.”

What followed was the Emotionalist Manifesto, which laments how the real and the virtual are becoming indistinguishable, while digital “systems monitor and mediate” all activity.

Calling for the Emotional city, not the Smart city, it stresses that while “the idea of emotion in architecture is not new”, today’s “Emotionalism, based on the supremacy of human emotions”, responds to the challenges of “automated design by AI”.

A loose, roughly 25-strong collective calling itself The Emotionalists has since crystallised around that position, Wright’s ideas having “resonated with many artists, academics and architects around the world”, says So.

Enter The Blue. Although the concept of emotional architecture was proposed in the 1950s by architect Luis Barragán and sculptor Mathias Goeritz to challenge modernist functionalism, So declares The Blue “the first project designed with Emotionalist principles in mind”.

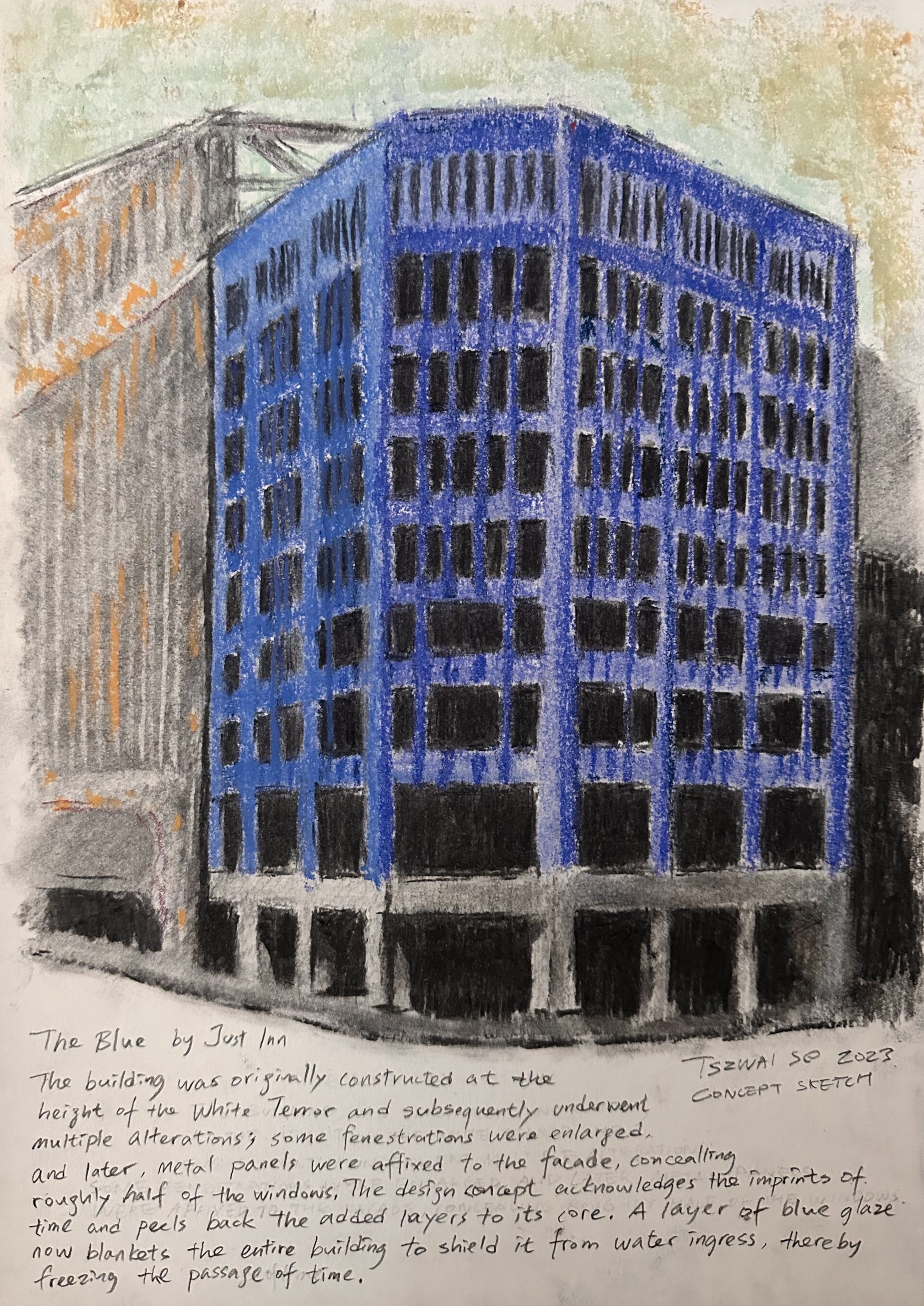

At 22,000 sq ft (2,040 square metres) and 11 storeys (including the basement), it was commissioned by small Taiwanese chain Just Inn and designed by So, of Spheron Architects. An early press release fittingly describes it as an “experimental retrofit art hotel”.

“Some Taipei artists joined the collective and risked their money to commission this first Emotionalist building, so in a way it was a happy coincidence,” says So. “[But] it was a very risky experiment, because we didn’t really know what makes an Emotionalist building ourselves, so we learned by doing.”

If joy is the sort of emotion The Blue’s hoteliers might wish for their guests, its absence also played a part in its creation. So tells of how two of the three company owners, who met about 20 years ago at university, often travelled together on a budget and “stayed in some of the most horrendous hostels or hotels around the world”.

One Russian hostel they found “dehumanising, smelly, terrible and with a lack of soul”, whereas “they felt they could bring joy” to holiday accommodation and “add art to the experience”. At the expense of profit? “For them, it’s not really about attracting more customers, but about sharing their love of art,” says So.

Future exhibitions will occupy a ground floor “deliberately left bare to reduce the use of cement, which is carbon intensive. And we don’t want to cover its beautiful, board-formed exposed concrete patterns with another cement layer”.

The temptation, however clichéd, is to regard the refurbished building – constructed as an office block in 1970 and recently operated by another hotel chain – as a work of art itself. Because in many ways it is.

The shade of blue created for the exterior, So believes, is unique. “Once we had stripped the metal cladding, the original, typical Taiwanese mosaic tiles were revealed,” he says. “But many were peeling off and there was water ingress.

“A full restoration was impossible because Taiwan doesn’t produce those tiles any more and the only practical way to stop water entering was to seal the building” – with a thin layer of cement. That provoked debate about a possible uniform, exterior colour.

“I suggested blue,” says So. “It resonated with the clients and we started researching shades.” Eventually, and notwithstanding blue’s role as a psychologically “calming” colour, the serendipitous gift from an artist in the collective, of a model of a Taiwan blue magpie, provided the key.

“It was a long process,” admits So, “but then we copied what the artist Yves Klein did and invented our own blue.”

“The result is less important than the process, though, which was about people coming together and getting their hands dirty, mixing the colour with their hands. That’s what distinguishes this blue.”

Inside, the “tactile” hotel finds favour “with many people for its quirks and dreamy, dimly lit atmospheric spaces, with different textures”, says So. “And we used many recycled materials from the building: the chandelier above the reception desk is made of waste steel and the desk itself is made from a steel staircase.

“All the furniture was kept and the doors sanded down manually to add a human touch. Unusually for a commercial project, almost every design decision was based on the clients’ and designer’s emotions: how we felt about broken relationships, midlife crises, bereavement and so on,” he adds.

“We opened up and allowed ourselves to be vulnerable: the smashed glass from the building embedded in the lobby floor, for example, is a tribute to the late mother of one of the clients and can be interpreted as teardrops or fallen leaves.”

Inscribed on the pavement outside the hotel, on its concrete pillars and, again on the lobby floor, are quotations, concerning AI and the future, solicited from 50 artists and architects, including Francine Houben, co-founder of Dutch architectural firm Mecanoo.

Their wisdom has already provoked much intrigue from passers-by, as did the hotel’s big reveal.

“People’s reactions don’t lie,” says So. “The day the scaffolding came down, it was captivating: central Taipei actually paused for a moment.”

In the lengthening shadow of AI, authentic architecture still provokes a reaction. Hate it or love it.