‘The simplest, dumbest materials’: how art gallery conversion painted silver stands out by blending in

- Hong Kong contemporary art gallery Kiang Malingue announces itself with its eye-catching silver exterior. The bold adaptive reuse continues inside

- A 1960s six-storey building has become a four-floor gallery housing a white cube, but with walls on other floors stripped back to their raw concrete

Here’s how to find the Kiang Malingue gallery on Sik On Street, if you’re walking from Wan Chai MTR station. When Google Maps announces: “You’ve arrived at your destination,” your journey has really just begun.

Scan Queen’s Road East for a Middle Eastern takeaway and a Chinese furniture shop. The gap between them is the “secret” entrance hiding in plain sight.

Make your way through the portal and gird for the steep passage ahead. The glint from a slim, six-storey-tall building will lead to your goal.

Monolithically silver – architect Rem Koolhaas went for gold with his Prada Foundation venue in Milan, Italy – the contemporary art gallery announces itself with other bold gestures besides: 12 men schlepped its 400kg main door up 33 steps.

“Hong Kong people are used to it,” says Gilles Vanderstocken, of Beau Architects, when asked about the challenges of building on a stepped site with no road frontage. “We see that more as a site constraint,” adds the studio’s other founder and director, Charlotte Lafont-Hugo.

Apart from the door (which was supposed to weigh in at 200kg), apparently little else required heavy lifting.

The “magic path”, as she now calls it, cast a spell when they were shown what would become Lorraine Kiang and Edouard Malingue’s fifth art space with Beau Architects.

The first, now closed, inhabited a Central office tower; the second, shuttered during Covid, a Shanghai shopping mall. The third and fourth, on two floors of a warehouse in Aberdeen, on the south side of Hong Kong Island, came about partly because the Wan Chai venue took three long years, instead of the anticipated one-and-a-half, to complete.

Which should come as no surprise, given Hong Kong’s recent history. Several months after the tenement building’s purchase, the 2019 Hong Kong anti-government protests began. “Then Covid,” Malingue says. “So getting answers was slower.”

Add to that bureaucracy (a lift proposal, denied, cost half a year; a water tank debacle probably more, in terms of angst) and it becomes clear why finishing the project last September was a milestone – for the art world as well.

Now, with the gallery showing its third exhibition – works by Vietnamese-American multimedia artist Tiffany Chung will be on display from March 20 to May 6 – the 1960s building feels like an indelible part of the landscape.

Rejuvenated also on the inside by peeling back the decades, it is a bold example of adaptive reuse that aims to reveal rather than conceal, largely by removing instead of adding.

Original concrete is exposed, for instance, its blemishes balanced by surrounding surfaces of smoother texture. That includes the noteworthy Shanghai plaster, a cement-based architectural finish that came on the scene a century ago and whose beauty is finding new appreciation (see Tried + tested).

Then there are the spaces themselves. While the bottom (and biggest) floor accommodated a Mandarin-language school for children, the levels above housed a 430 sq ft flat per floor. All have become art spaces of different character and purpose, although one is, as Lafont-Hugo says, “a joke” (of the in kind).

By removing two floors the architects were able to create a double-height white cube. A second, lofty cube occupies the level above.

“We’ve been complaining about the omnipresence of the white cube,” says Malingue, referring to the art world’s continuing debate about the modernist penchant for exhibiting works in spaces that check sensations at the door. But when the opportunity arose to create a “real white cube” with six square faces, the concept was, apparently, irresistible.

“It can look very impressive but there is something humorous about it,” Malingue says.

Recalling critic Brian O’Doherty, whose provocative 1976 three-essay series “Inside the White Cube” scrutinised gallery-space ideology, Lafont-Hugo remembers discussions years ago with Kiang and Malingue, who stressed: “We want visitors to understand there’s a backstage. We don’t want people inside completely neutralised rooms.”

Lafont-Hugo adds: “The point is to show people the different typologies of art spaces that exist.”

The new gallery offers that in spades, including on the first floor, where bifold doors allow access to a balcony of potted plants at the front and a spacious leafy terrace at the other end.

If this first level feels compressed and long, it is due in part to the raised floor accommodating cables and other gubbins below, as well as to a sleek galley kitchen stretching along almost an entire side of the room.

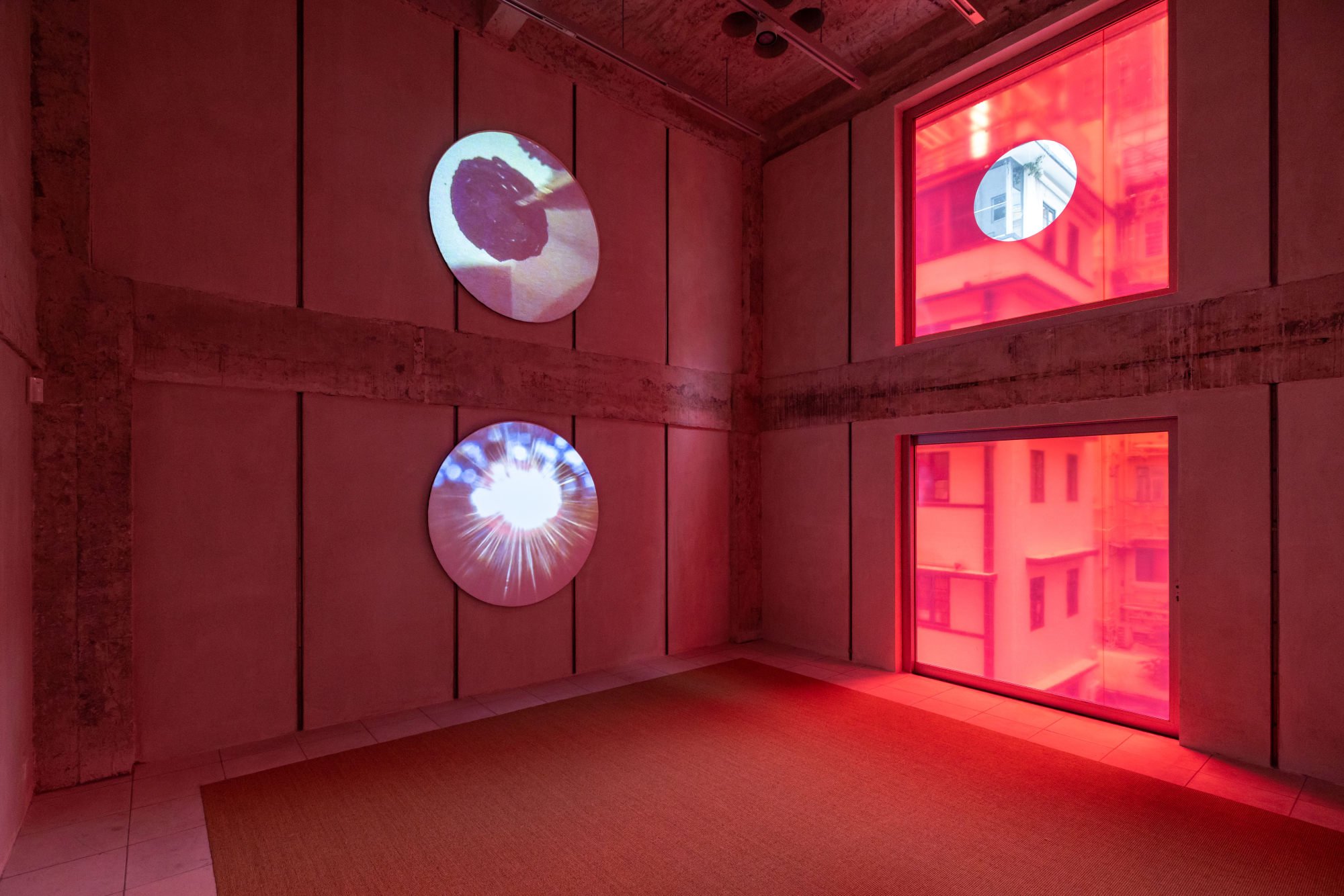

Here and elsewhere air conditioners are felt but not seen, their circular vents, in fact, doubling as motifs that complement the deep round windows providing glimpses of the quiet, residential neighbourhood.

Sitting by the kitchen at a wooden dining table, Kiang, Malingue’s partner in life and business, says that not losing that “sense of domesticity” was an important part of the design brief because of the building’s original purpose. So was the essence of being in Wan Chai and that “claustrophobic sense of being close to your neighbours”, she adds.

Two large windows in the top cube provide dramatic vistas of urban closeness. But one unintended effect of fixing the gaze on buildings close by is the introspection it fosters.

Outside, the gallery oddly stands out by blending in, because its morphology has been preserved (original windows, infilled with bricks angled at 45 degrees, flank the new openings). But from within, one realises just how much has been adapted, reused and transformed.

Kismet can take some credit, especially for the building’s new-old face.

“On a bright Sunday morning Lorraine and I were sitting at the top of the stairway looking at the building, and saw our son running down the stairs with a shiny silver parka,” Malingue says. “We both thought at the same time that it would be super cool to use a similar silver colour for the building.”

Silver lamp posts in the area reinforced the choice.

But there was also the attraction of taking the easiest, most cost-effective route to homogenise the modifications, Vanderstocken says.

“We like to make very strong gestures with the simplest, dumbest materials possible,” he adds, explaining that for the all-important front, off-the-shelf galvanised paint, similar to the kind used on light poles, was the obvious solution.

The effect is magic.

Tried + tested

A snapshot of the Shanghai plaster samples created for the walls of the Kiang Malingue gallery is a memento of the effort that went into finding the right ingredients, and proportions needed, to create the cement-based finish for some of the building’s inner walls. It took 22 attempts.

Little wonder that, at times, they felt like they were going mad, recalls Beau Architects’ Gilles Vanderstocken, who describes how their plasterer experimented, on a sheet of plastic, adding a bit more sand here, cement there, with different quantities of finely crushed stone.

The plaster’s importance to the gallery’s muted aesthetic was not lost on the craftsman, as can be seen in notes on some of the trial runs, reading, in Chinese, white cement, yellow and red sand and white pebbles (large and small).

According to British architect and scholar Charles Lai, Shanghai plaster emerged in Hong Kong around the mid-1920s and quickly became a popular choice for modern buildings in the city and elsewhere in colonial Southeast Asia.

“It was in this building and it was something we discovered during the demolition,” says Beau Architects’ Charlotte Lafont-Hugo. Wanting a more contemporary hue than was found on the original walls, the team went down a rabbit hole of colour matching, and learning, to produce an architectural finish that complemented the brutal concrete surfaces.

Although arduous, the sifu’s process was “a pleasure” to watch, remembers Vanderstocken. “It was like looking at an artist at work.”